In Tokaj (2): The grassroots revolution

Posted on 22 January 2010

Tokaj made its name on botrytised sweet wines, aszú, yet as mentioned in my previous post, these have fallen out of fashion and become notoriously difficult to sell both on the domestic market and export. As Tokaj has had to find a proper productive balance to survive at all – it’s actually a work in progress – the unthinkable has happened: it’s now possible to taste through several dozen Tokaj wines and climb to 90+ ratings without having a single botrytis wines on the table. It’s what happened to me last Friday when I met with the young up-and-coming vintners of the Tokaji Bormívelők Társarsága (that’s Tokaj Wine Artisans’ Society, you’ve guessed it, but let’s call it TBT hereafter).

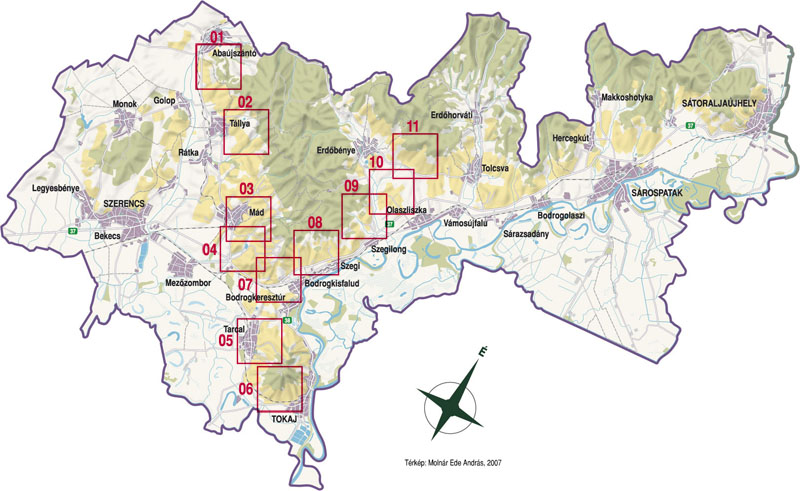

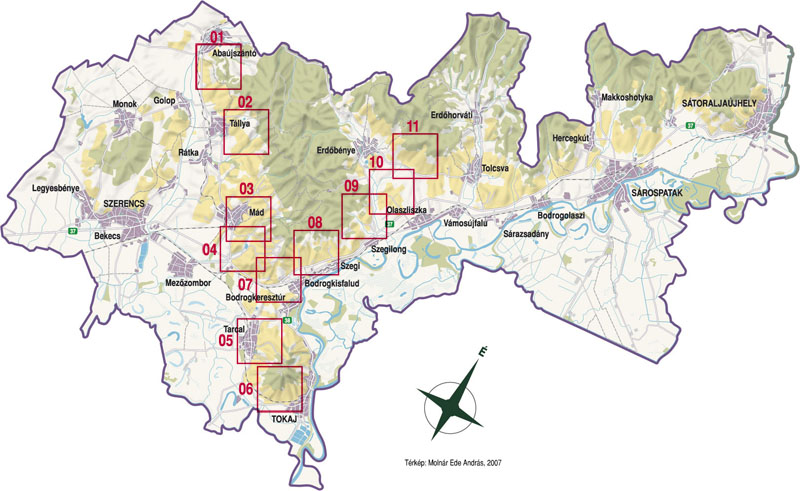

Classified vineyards of Tokaj. © TBT (click for more info).

They’re a weird bunch really. Zsolt Berger was a business journalist before he came to Tokaj and started making wine out of the blue. Attila Homonna (see a brief entry about him here) was a successful marketing guy and then owned a wine shop in Debrecen but he got the Tokaj bug too; it’s all made remarkable by the fact that after 8 vintages made he’s still only 35. Judit Bodó (née Bott, which is the name of her winery) came from Slovakia without the merest experience in winemaking (though she’s travelled to vineyards in Alto Adige and South Africa to learn, on her own expenses); in the first couple of years of production her dry Furmints instantly propelled her into the regional superleague. There are arguably some very successful autodidacts in the wine world but nowhere in such high proportion.

The fact that it took a young generation with little or no background in winemaking to produce some of the most breathtaking dry wines in Tokaj is a paradox that one day, I hope, will become the subject of a sociological and psychological study. But it’s another fact that the heroes of the 1990s focused on the sweet wines and haven’t really come to terms with making world-class dries. (The situation is vaguely similar to that of port and dry Douro wines in Portugal). Sure, there have been some successful bottlings such as Oremus’ Burgundian Mandolás or János Árvay’s turbocharged (and excessive) single-vineyard Furmints, but it was not the breakthrough Tokaj needed to establish itself firmly on the great dry white wine map of the world.

Zsolt Berger tasting a luminous 2009.

It was István Szepsy, the region’s veteran and consistently the author of its greatest sweet aszús, who showed the way with his 2000 Úrágya Furmint. Old vineyards, low yields, ripe but unbotrytised grapes, oak fermentation, big structure (but balanced alcohol) and a touch of residual sugar to balance Furmint’s notoriously punchy acids: Szepsy’s recipe for success has now been developed by a large group of dedicated estates.

They all have a few points in common: they are small (‘boutique’ or ‘garage’ is a good descriptor here), own pockets of vines in Tokaj’s most prestigious vineyards (that were listed in 1700 in Europe’s earliest attempt at vineyard classification), make little or no sweet wine, and have an ambition of making Tokaj a great terroir white, rather than a FMCG marketable alternative to save the company cashflow. In 2006 the Artisans’ Society (TBT) was created: a list of classified crus was drawn, members meet, talk and taste together, agreeing on which submitted wines adhere to the strict criteria and the overall philosophy of the project. Those that pass the exam get the TBT logo. The system works a bit like the Grosses Gewächs one in Germany, and in due time will hopefully become the foundation for Tokaj’s official premiers and grands crus.

A happy TBT bunch: Hajnalka Prácser of Erszébet, Stéphanie Berecz of Kikelet, Sarolta Bárdos of Tokaj Nobilis with her 3-month-old daughter, Judit Bodó of Bott, and Zoltán Asztalos of Néktar.

We’ve tasted some impossibly limpid, pithy, stoney-mineral 2007s and 2008s from Attila Homonna, and a very idiosyncratic 2008 Palandor Furmint from Karádi & Berger: peppery, violent, very volcanic indeed, with a rare expressiveness (the 2007 is a touch shier and there is also a 2003 Dry Szamorodni, essentially a mildly oxidative version of the same wine). We’ve tasted the impressive 2007 Öreg Király from Károly Barta, vinified by Homonna from high-perched terraces in this, perhaps Tokaj’s most majestic and uncompromisingly mineral cru. Béla Török showed some fun wines including a 2008 semi-dry Muscat of rarely seen minerality. Stéphanie & Zsolt Berecz from the Kikelet estate poured a delicious sweet 2007 Late Harvest but also my favourite expression of Hárslevelű (Tokaj’s second grape variety), zesty, witty, springtime-refreshing instead of the chunky, alcoholic, oxidative thing it so often becomes. Sarolta Bárdos and Péter Molnár of Tokaj Nobilis also make an excellent Hárs as well as a pure and limey 2008 Furmint from the cru of Barakonyi (and an intriguing semi-sweet Spätlese-styled Kövérszőlő, from Tokaj’s oldest, almost extinct variety). Judit Bott surpassed herself with a 2008 Csontos Furmint that has about the best mineral and structural balance I’ve seen in the region.

I tasted 60 Tokajs on that Friday and there was hardly a sweet botrytised aszú in sight. And yet it was as exciting as if I’d been in, say, Chablis or Rüdesheim. Revolutions always start quietly but eventually turn our world upside down. This one is no exception.