Quinta das Maias Malvasia Fina 2006

Portugal’s white wines deserve to be better known.

Portugal’s white wines deserve to be better known.

So how is this Saint-Joseph 2007 showing? From a good vintage, this is drinking nicely now, though a year or two more in bottle will do no harm. What’s really exciting here is the typicity – this is Northern Syrah at its most recognisable, with a mildly flowery, raspberryish nose, high acidity, tight tannins, and an almost Burgundian sense of refreshment to it. There’s indeed quite a bit of Pinot Noir/Gamay character in this wine. It made me think of old books about the Rhône Valley where Syrah from Côte-Rôtie and other appellations here was often defined as the southern outpost of Burgundian-styled wine (as opposed to the fully Mediterranean Syrahs further down south). Back in the 1970s and 1980s, many wines had to be chaptalised here to ever reach 12,5% alc. These times seem as distant as the Hundred Years’ War now: Côte-Rôtie has become full of 14% Parkerized blockbusters. While vinified in a modern way, this Saint-Joseph captures the northern zest well.

I feel a bit ambiguous about it, though. It’s really a rather simple wine, with not a mass of dimension (interestingly it got a lowish 14/20 from Bettane & Desseauve), and the asking price of 18€ seems a bit steep: you’re surely paying a premium for the Jaboulet and Perrin names on the label. For what is a middle-class (though ambitious) appellation, it’s a bit disturbing to see an entry-level wine like this priced so high. On the other hand, the winemaking here is brilliant: there’s not a milligram of oak noticeable in the flavour, and the wine is perfectly balanced with finely gauged acids and tannins. The quality of the latter is top-notch. In the end I enjoyed this quite a bit, but I need to start saving for this producer’s Hermitage which nears 50€ per bottle.

|

| Quality inspection in an amphorae room, Kakheti, Georgia. |

This wine is presenting all the characteristics of an amphora white in high intensity: the colour is a deep orange-amber, there is little direct fresh fruitiness on the nose but a lot of complexity and intensity: apple skins, dried apricots, quince and peach preserve, cinnamon, cloves, pepper, vanilla, and a lot of raisins. What is really interesting here is how this distinguishes itself from other amphora whites: instead of rustic phenolic oxidativeness it is showing very balanced and actually elegant, with a silky, even texture and satisfactory freshness (not easy to achieve in the style), clean, juicy and mildly mineral where many similar wines are rough, fruitless and alcoholic. This wine is not a curiosity but a fully valid bottle – surely made in an ‘alternative’ style but without sacrificing drinkability and a sense of linearity. I’m a big fan of Georgian wines, and I love to try an amphora white when I have the occasion. This might be one of the best wines I’ve had in both departments.

|

| Grape harvest underway in Kakheti, Georgia (September 2005). |

This post also appears in Hungarian on A Művelt Alkoholista.

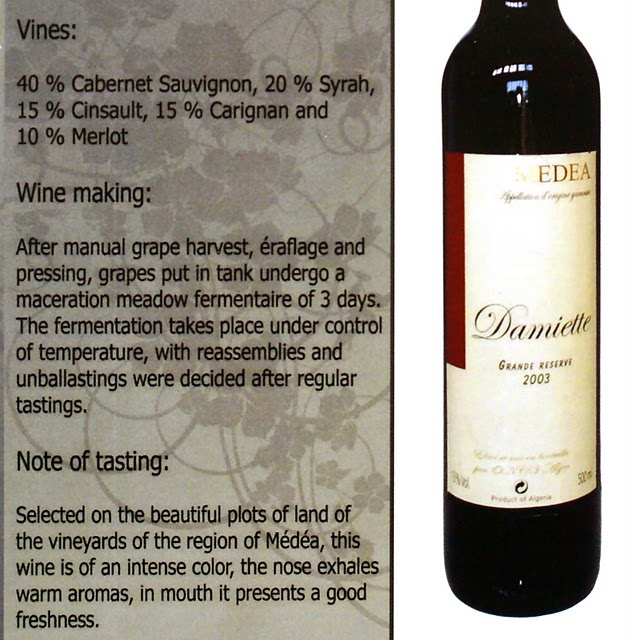

The French legacy still continues: in the grape varieties that are grown – the Rhône classics such as Grenache, Carignan, Cinsault, Syrah as well as some Cabernet Sauvignon – and the slightly overambitious appellation d’origine garantie system that distinguishes seven major viticultural zones. The vineyard locations are actually exciting: high on the Atlas plateau at 600–900 m above sea level, with large temperature difference between night and day.

I tasted these wines several times in the past, and this was my most complete session with 12 bottlings. The Coteaux de Tlemcen 2008 is certainly rather bad, dirty and faulty, while things such as the organic El Mordjane 2008 or the Médéa Château Tellagh 2008 were showing rather diluted and characterless. The traditional cuvées here included the Coteaux de Mascara 2008 and the multi-vintage Cuvée du Président. Made in a conservative Rhône style, these wines spend a long time in concrete tanks and used oak, and are perhaps released a tad late by today’s standards: colours are faded, fruit is low, the structure is mellowed and the focus is on a medium-bodied, food-friendly but not terribly expressive fruit & spice substance. There’s occasionally a bit of oxidation. I enjoy these wines for their simplicity and sense of restraint, though they are certainly not commercial.

|

| Algeria also has potential to make seriously good rosé. |

This was an interesting tasting. I wonder how well-suited the state-controlled and obviously slightly conservative management of the ONCV is to face the challenges of a global wine market. Quality requires investments but also a vision. Yet with a cleaner approach to winemaking and a more selective viticulture, Algeria seems to have all the assets to produce plentiful, reliable commercial wine in a style that I’d prefer to what can be found in budget bottlings from Chile or South Africa today.

|

| Algeria also needs to invest in promotion materials: Google Translate of tastings notes is not good. |

Bosco Eliceo – a confidential wine-making zone on Italy’s Po Delta – is underperforming. But there’s no better wine than its fizzy dry red to match with the famous Comacchio eel.

An incredible tasting of old Rieslings – we went back to 1909! Most were still very much alive. And even more surprisingly – bone-dry, even though you’d expect a Riesling to have residual sugar to age for so long. Not here!