On the Etna (2)

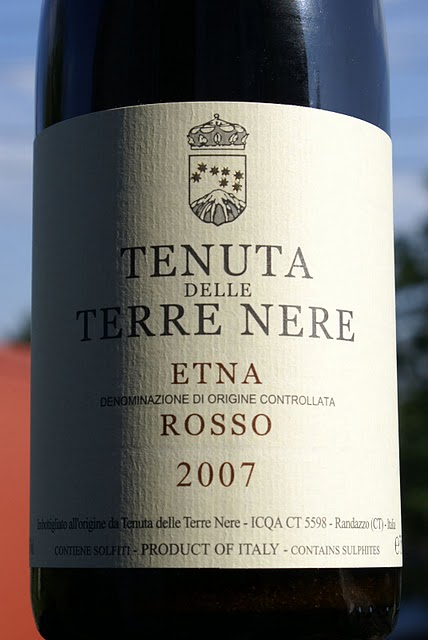

As per my habit of gauging my palate to the forthcoming bunch of wines I opened the Tenuta delle Terre Nere Etna Rosso 2007. Terre Nere is the Etna venture of

Marc De Grazia, an influential importer of Italian wines into the US that has been one of the architects of Italian wine’s success on the American market. Interestingly, while much of De Grazia’s original catalogue represented some of the most modern trends in Italian wine (including some new French oak-aged Barolos and Barbarescos), the wines of Terre Nere show quite some respect for tradition. It’s evident by the light bricky colour of this red and also its bouquet: showing lots of finesse and a subdued minerality, it isn’t overly fruity or upfront. The red wines of Etna are often compared to burgundies (and the local grape, Nerello, is yet another ‘Pinot Noir of the Mediterranean’), and while it’s often an abused comparison, here it’s really right. The ripe, fleshy, gently spicy, hauntingly flowery aroma of this 2007 could well be that of a warm-vintage Volnay or Chambolle.The flavour of this wine is really interesting. The balance is quite unique. Acidity is not very high but there is a mineral coolness and restraint at the core; the fruity notes echo the nose with fleshy cherries and ripe currants, and there is a perfumed flowery undertone. Surprisingly for a wine with such light body and flowery finesse, the tannins on the finish are quite sturdy. Finesse, minerality and tannins: these elements do not often go together in a red wine. This 2007, Terre Nere’s basic cuvée (they also make several single-vineyard bottlings), is really overdelivering for the price, developing very well in the glass. It’s boding well for my Etna excursion – read more about it soon on this blog.

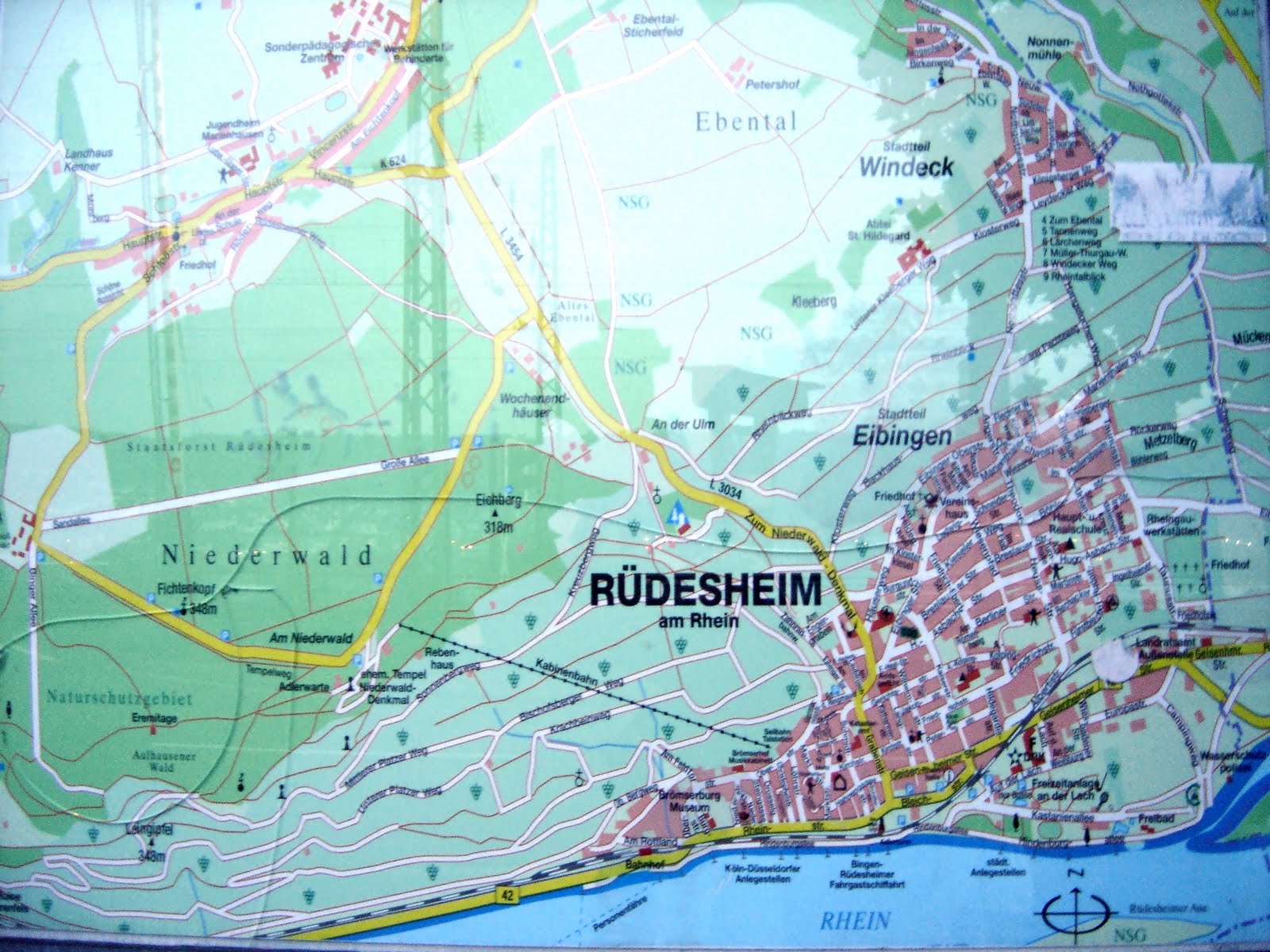

Sunrise over Rüdesheim (photo quality courtesy of Sony Ericsson).

Sunrise over Rüdesheim (photo quality courtesy of Sony Ericsson).Mind you, these Rieslings are acidic. The 2008 Rüdesheim Estate (a village-level wine from various crus) has no less than 9.6g of acidity (and 6.9g of residual sugar) and yet it’s a wine of ripe mineral aromas and of engaging purity on the palate. Theresa Breuer says they were concerned by the very high analytical figures and even tried some deacidification but the damage to the wine’s balance was huge. This bottling, like its slightly more powerful sibling of the 2008 Terra Montosa (made from declassified lots of Breuer’s grands crus) shows a warm sea salinity that reminded me of Chablis.

Berg Rottland and Berg Schlossberg are to your left.

Berg Rottland and Berg Schlossberg are to your left.We finished the evening at Breuer’s crowded

Schloss Rüdesheim Weinstube, starting with a wine taster’s best friend – cold beer, and rounding off the session with a bottle of Breuer’s enjoyable Riesling Brut. Come here really hungry as the portions are huge, and be prepared for Japanese parties and a lot of singing…My extensive report from the largest tasting of top German Rieslings. All regions comprehensively reviewed.

There are two types of wines that could hardly be held in higher esteem by wine journos, and yet are quite unpopular with the wider drinking ‘public’: dry sherry and dry Riesling. I can recall the names of at least a hundred colleagues who have sung the praise of Jerez seco and Riesling trocken. ‘The wine world’s best-kept secret’, ‘ridiculously good value’, ‘when will humanity open its eyes to the greatness of these wines’ etc.

There are two types of wines that could hardly be held in higher esteem by wine journos, and yet are quite unpopular with the wider drinking ‘public’: dry sherry and dry Riesling. I can recall the names of at least a hundred colleagues who have sung the praise of Jerez seco and Riesling trocken. ‘The wine world’s best-kept secret’, ‘ridiculously good value’, ‘when will humanity open its eyes to the greatness of these wines’ etc.

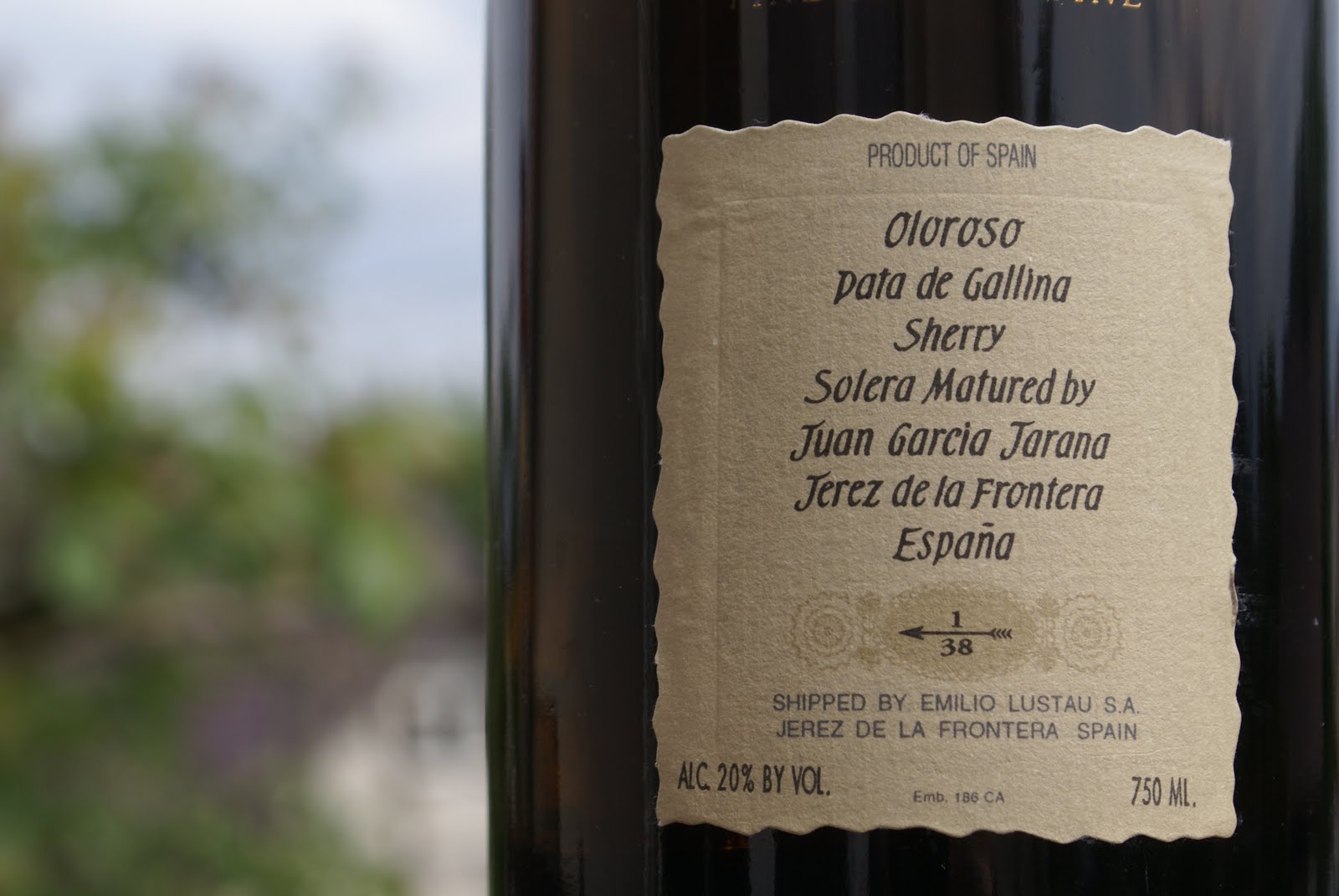

While dry Riesling in the last few years has made significant inroads and now can hardly be said to be ‘unpopular’ (although it still loses to sweet Riesling on such markets as the US and the UK, I think), dry sherry remains a commercial disaster that’s only surviving thanks to sales of the lightest style, fino sherry in Spain and abroad. The longer-aged, more complex styles like amontillado, palo cortado and especially oloroso are an acquired taste and have been relegated to a shrinking niche.

I don’t drink enough of these (supply in Poland is non-existent), and every time I do, I’m reminded how much I’m missing. These wines belong to the most compelling anywhere. But I’m also reminded how difficult it is to appreciate them from time to time. Delving into these deeply oxidised, unfruity, nutty, at times challengingly acidic and salty flavours requires a complete reset. If you open a bottle of oloroso between a Chardonnay and a Rioja, chances are you’ll find it repulsive. It really needs to be a regular exercise. There’s also no way to forget their alcoholic strength: while the 20% in an oloroso are as balanced as you’ll ever find, it’s not a wine you can drink in quantity, also because it’s so intense and mouth-filling.

The bottle I’m having today is among the very best sherries available on the market. From the négociant house of Emilio Lustau comes this Oloroso Pata de Gallina 1/38, matured by Juan García Jarana. I’ll spare you the technicalities (it’s basically a micro-production from a single grower, which is a very unusual thing in the world of sherry, normally a classic blended and branded wine) and will just say it’s a mindblowingly complex wine. I could write page after page of aroma descriptors and wouldn’t be exhaustive. There’s a unique combination of almondy, nutty, marzipanny, wafery, pâtisserie notes with nuanced fruits ranging from orange and lemon to raspberry, heavier spicy notes of mulled wine, bitter chocolate and caramel, a raisiney richness but also lots of lifted, sandalwoody, varnishy, almost vinegarish scents. But it’s all in balance. It’s a wine that keeps changing in the glass: over half an hour it’s really like an aromatic journey over an amazingly complex landscape. I sit in silence and awe as the wine tells its epic story.

The other remarkable thing is that I’m finishing this bottle that was opened on 30th December 2007. That’s no joke. December 2007, not 2008. That’s 596 days! And I must say the wine is still very much alive. I can’t say it’s unchanged – it has surely lost some complexity – but is still offering more than a fair bit of impact, and length is as staggering as usually in a good oloroso. The wine was completely oxidised in oak barrels over something like twenty years (it’s hard to give a precise period of ageing, as the barrels were regularly refreshed with new wine) and it really couldn’t care less about being exposed to oxygen now. Only madeira can approach this durability. It’s making this wine even more unique. Please drink more dry sherry!

To Minervois or not to Minervois?

It’ll be a tough job. No other grape has been denigrated so much in the last few decades. In France, authorities to their utmost to get rid of Carignan wherever they can. You can cash in thousands of €€ just by uprooting Carignan vineyards, no matter how good the wine they produce. In the variety’s traditional stronghold, the Languedoc, every single AOC appellation has a maximum limit of this grape in the blend (usually 40%; 50% in Corbières; the backwater AOC of

Fitou is an honourable exception in requiring a minimum of 30% Carignan).Until recently, Carignan was charged with all possible crimes. It was deemed responsible for the major wine glut of the Languedoc – whereas the real culprit were the heroic yields to which this flexible grape was harnessed (300 hl/ha was, apparently, far from being the record). Carignan was alleged to be a ‘rustic’ grape, unsuitable for ‘modern’ viticulture (read: mechanical harvesting) and its wines unappealing to ‘contemporary’ tastes (read: too acidic). It was also judged a ‘clonal disaster’ (but why did you ask nurseries for high-yielding clones back in the 1970s?).

The slow change in Carignan appreciation we currently witness is partly the merit of growers like the Bojanowskis who show the potential of the grape with low yields and old vines (these can run up to a 120 years in places), and partly that of the wine zone of

Priorat in Catalonia. Here, schistous soils, high elevations and a semi-Mediterranean climate results in some stunningly rich wines that have been making the headlines for a decade now. While the early successes of Priorat were based on the Garnatxa (Grenache) grape, there’s an increasing interest in the local Carinyena (Carignan), which helps to balanced Garnatxa’s sexiness with some meaty spice and minerality; Carinyena-dominated wines such as Cims de Porrera, Clos Martinet and Vall-Llach are among the most exciting not only of Catalonia but of entire southern Europe. With such stunning wines being made with Carignan, it’s no wonder producers all around the huge crescent of Mediterranean land that was once ruled by Aragon (from Valencia to Sardinia) where Carignan was the dominating variety are starting to pay much more attention to its potential.If you look at it, Carignan is remarkably well-adapted to the various terroirs of southern France and north-eastern Spain. It ripens late so can be cultivated even in the hottest vineyards of Priorat and Collioure, yet buds late too so you can plant it fairly high without fearing for spring frosts (Priorat has plantings up to 900 m). While the new clones can yield generously resulting in pale diluted wines, with a bit of discipline and well-drained soils the grape is capable of great concentration (more so than Grenache, I think). It has a very deep colour (even more so than Syrah; in fact, it’s been used for years as a colouring ingredient in blends) that is very stable over time (unlike Cinsault, the ‘other’ traditional variety of the Languedoc that loses colours quickly). It’s also usefully high in acidity and very resistant to oxidation (unlike Grenache); it actually has a tendency towards reduction, producing (courtesy of brett, more often than note) the meaty, barnyardy bouquets that earned it the adjective of ‘rustic’.

Nicole and John Bojanowski pruning the old vineyards. © Clos du Gravillas.

Lo Vièlh is Clos du Gravillas’ top red (they also make a great job in the lighter bottlings); the top white is L’Inattendu. This wine, produced since 1999, was one of the first varietal versions (now there are far more) of Grenache Gris, one of several natural clones of the Grenache family: a pink-skinned version that’s traditionally been used to add fruit to oxidative sweet wines like Banyuls, or finesse to dry reds. It packs in a lot of punch and the 14% alcohol here can be considered a relatively light rendition.

If you’re thinking of Languedoc as a land of bland apéritif whites made from Clairette or, worse, Chardonnay, the L’Inattendu 2007 will come as a shock. It’s a very structured, brutally mineral wine that’s positively anti-aperitifey. Aromatically a bit challenging (ranging from fallen apple through onion to white pepper), it explodes on the palate with saline sappiness and rocky austerity. I think this sees new oak but there’s so much power to these grapes that they’ve eaten it all. It’s bone-dry, broad-shouldered but not exactly rich; a sort of sturdy, no-nonsense, caloric white wine that makes me think of lonely shepherds in the mountains having a cup of wine on a chilly August evening. If you’re not up in the mountains lonely, I’d serve this with food, although finding a good match will not be easy: the Bojanowskis suggest anchovies (notoriously difficult to pair with), I’d try salted cod or perhaps, simply, a slab of hearty pain de campagne with salted goat butter… It’s another wine I’d love to try at age 10 but with a few thousand bottles made each year, my chances are low.

The mind behind the project is

Elisabetta Foradori, outstanding vigneronne from Trentino in northern Italy. So it’s no wonder the wines show a technical mastery, especially in their balanced extraction and deft use of oak. More importantly, however, the estate itself is really interesting. It consists of three blocks with an altitude ranging from 150 to 600 m. Combined with a fairly complex varietal composition – Sangiovese and Cabernet Franc dominate but there are bits of Mourvèdre, Grenache, Carignan, Marselan and Alicante (an ancient vine from the Maremma, usually associated with Grenache, and probably brought to these coasts during the Aragon rule of the western Mediterranean) – this allows for a balanced estate wine, avoiding the extremes of high-acid austerity (a danger in the higher-grown Sangioveses) and unstructured high-alcohol fruitiness (when Languedoc varieties are grown on low altitudes). It’s an example of reinterpreted (or man-made, if you prefer) terroir. Italians have a very good term: vino d’autore.I’ve followed this project since inception, and have been impressed by how quickly it reached an excellent cruising speed. The third vintage of Ampeleia – 2004 – already is a brilliant wine, deep, mineral, brooding, fruity and structured at the same time, with plenty of interest. (It’s an excellent vintage to breech now). Here I’ve had a look at the Ampeleia 2005. Dominated by 50% Cabernet Franc and aged in 40% new oak, it’s currently going through a dumb phase (in fact it was more expressive a year ago upon release) but there’s no denying the excellent quality of fruit. Although Sangiovese makes up only 30% of the blend, it’s quite present with a bitter cherry profile, and good sustaining minerality. There’s also quite some richness and concentration, and a distinctive pink-flowery scent that I find Ampeleia’s true hallmark. Tannins are ripe and acidity is not very high, confirming the Mediterranean architecture of this. My bottles will remain in the cellar for a few more years while I finish the 2004s. At around 25€, Ampeleia is really affordable compared to some more famous labels from the Maremma.

I’ve also tasted the second vintage of Ampeleia’s new ‘second-label’ wine, Kepos 2007. Upon release, I didn’t quite like the 2006, finding it excessively rich, a little flabby and macerative. This vintage is considerably better. It’s medium-bodied with a lovely transparent colour and a blissful nose of tulips and peonies, followed by impeccably clean raspberries and a juicy, clean, vibrant palate. Very good length, too. It’s best slightly chilled and enjoyed straight after opening with no excessive airing. I’ve also opened a bottle of the 2006 vintage to see its evolution, which I must say is for the better. I’ve been a little harsh to this wine in its youth. It’s not all that overripe today, if less flowery, more peppery and alcoholic than the 2007, and also more tannic. It’s ripe but not overripe, oaky but not overoaked, fruity but not ridiculous, soft but not flabby, and another well-vinified wine with plenty of content and seriousness. Kepos is also reasonably priced at around 16€. Based on the five ‘Mediterranean’ varieties (with no Sangiovese or Cabernet Franc), I wonder how its introduction will influence the blend of the main Ampeleia label.

But in my case, the tea had to be special. With so many old wine vintages being poured, I wanted a tea with several decades on it. Old puer was best avoided, though, as the taste could be challenging to some diners. So I went for this 1976 Baozhong from Tea Masters (see description here

; the tea is out of stock at the moment, although Stéphane says it might be available again in the autumn).Last week’s anniversary dinner was an eye-opener for this Baozhong, after circumstances forced me to change my brewing style. To accommodate so many people, I had to choose a really large pot. My choice went for this glass pot which contains roughly a liter:

It’s the equivalent of what is called ‘glass brewing’ or ‘bowl brewing’ (see discussions here

Looking at the wet leaves, it’s no surprise this tea is so good. The roast has been really virtuosic as many leaves are still dark green in colour (have a closer look at the twisted leaf to the far right of the photo below). And for their age, they are really impressively intact. On top of it, it’s a really inexpensive tea for its age (40€ / 100g). Dear Stéphane, I truly hope you can source some more!

Looking at the wet leaves, it’s no surprise this tea is so good. The roast has been really virtuosic as many leaves are still dark green in colour (have a closer look at the twisted leaf to the far right of the photo below). And for their age, they are really impressively intact. On top of it, it’s a really inexpensive tea for its age (40€ / 100g). Dear Stéphane, I truly hope you can source some more!