(More) Good Riesling

There was an exciting tutored seminar followed by a walk-around tasting. The former showcased top dry wines (chiefly belonging to the Erste Lage / Grosses Gewächs category). Even the Schloss Vollrads Erstes Gewächs 2007 which I usually don’t like (this historical estate is underperforming in my book) showed well, rich but bone-dry, with a spicy, almost brothy mineral presence and very good balance to its weight; a wine that reiterates my adulteration for the 2007 vintage. Another positive surprise was the Domdechant Werner Kirchenstück Erstes Gewächs 2006. I have a lot of sympathy for the Domdechant estate and its owner Franz Michel, one of German wine’s most engaging personalities, but I vastly prefer their sweet Kabinett and Spätlese wines to their trockens. In past vintages, I’ve found the EGs overly soft, often with a strange sunflower oil oxidative character. This 2006 was quite delicious, with surprising acidity for the vintage.

There was also an interesting range from Kesselstatt from the Mosel, including a dry Scharzhofberger Grosses Gewächs 2007, saline and citrusy with a balanced dryness but lacking a bit of depth and dimension, that was overshadowed by the Josephshöfer Erste Lage Spätlese 2006. It’s only in the Mosel that you’ll see Erste Lage wines with a degree of sweetness (they can be labelled as Kabinett, Spätlese and Auslese as in the ‘traditional’ German progression of sweet wines), and in the jungle of German wine classification this is one particularly tricky combination: how to make the grand cru status of the vineyard evident in a sweet wine context where traditionally, the mineral identity of various crus was not a priority? This wine shows how to address the issue: it’s hugely rich with a honeyed, almost oily texture from the late-harvested grapes, but showing a strong acidic backbone and an obvious minerality that will develop over the coming years and make this a really interesting bottle.

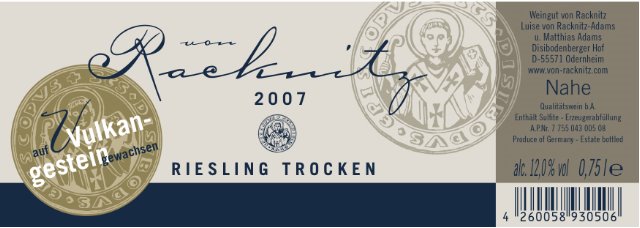

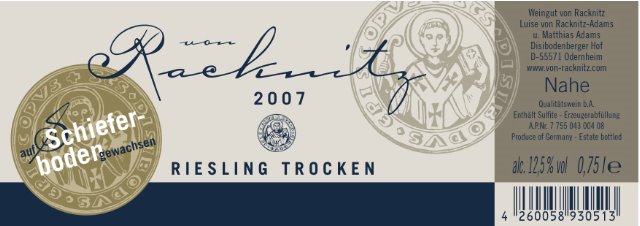

There was a producer new to me: Weingut von Racknitz from the small region of Nahe. It’s one of those estates that make Germany such a vibrant and exciting wine country. They have no fancy Erste Lage (they don’t belong to the VDP club) but – judging from the four wines I’ve tasted – very reliable quality and value for money across the range. The wines are organic and the Nahe Riesling trocken 2008 for 7.50€ is a delightfully fresh, greenish, driven rendition of the grape, while the Niederhäuser Klamm Riesling trocken 2007 is really impressive in its mineral definition, lemony poise and perfectly gauged residual sugar. For 11€ each, there’s also the interesting pair of Schieferboden 2007 – an austere and backward dry Riesling from slate, harmoniously dry with good body – and Vulkangestein 2007 – a more peppery but eventually supple and approachable wine from Nahe’s rare volcanic soils.

There was a producer new to me: Weingut von Racknitz from the small region of Nahe. It’s one of those estates that make Germany such a vibrant and exciting wine country. They have no fancy Erste Lage (they don’t belong to the VDP club) but – judging from the four wines I’ve tasted – very reliable quality and value for money across the range. The wines are organic and the Nahe Riesling trocken 2008 for 7.50€ is a delightfully fresh, greenish, driven rendition of the grape, while the Niederhäuser Klamm Riesling trocken 2007 is really impressive in its mineral definition, lemony poise and perfectly gauged residual sugar. For 11€ each, there’s also the interesting pair of Schieferboden 2007 – an austere and backward dry Riesling from slate, harmoniously dry with good body – and Vulkangestein 2007 – a more peppery but eventually supple and approachable wine from Nahe’s rare volcanic soils.

The Odernheimer Kloster Disibodenberg vineyard in the Nahe.

© Weingut von Racknitz

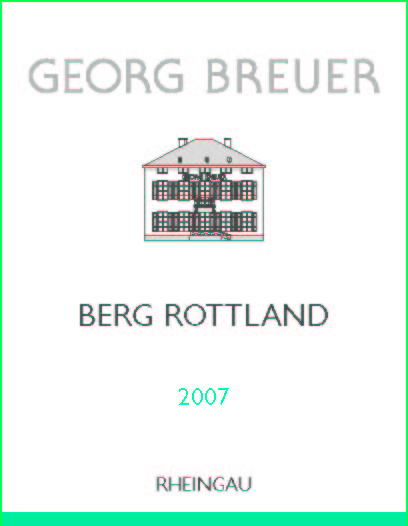

The Berg Rottland vineyard photographed from Bingen across the Rhine.

The Berg Rottland vineyard photographed from Bingen across the Rhine.