Touring Dalmatia: Grk

Posted on 2 December 2013

From Pelješac, it is a 20-minute ferry trip to the island of Korčula. One of the key islands in Dalmatia, it boasts over 2600 hours of sunshine per year, as well as an illustrious history of Mediterranean trade and ship building going back to ancient times, and then much developed by the Venetians who ruled the islands between 1255 and 1797. (Marco Polo, famous Venetian traveller and diplomat, was born on the island).

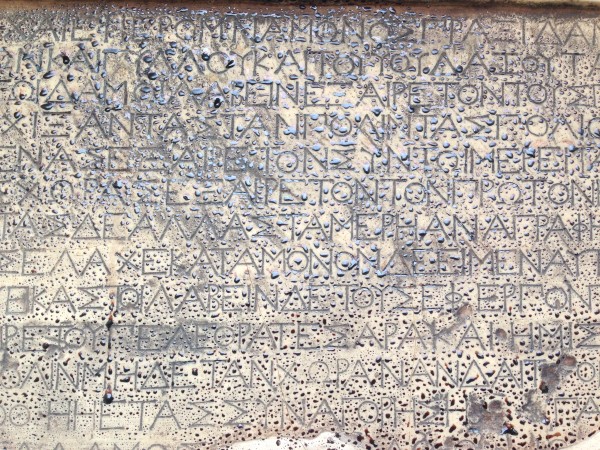

Courtesy of its limestone soils, Korčula is also a great habitat for the vine. Dalmatia as a whole boasts an incredible diversity of grape varieties: the island of Krk has Žlahtina, Pag has Gegić, Vis – Vugava, and Hvar – Bogdanuša. (Interestingly, these are white grapes, even though Dalmatia’s principal wine today is the red Plavac). Korčula’s main grape variety is Pošip (more on this in my next post). But at the eastern tip of the island, in the village of Lumbarda, there are 20 hectares left of a ancient grape variety found nowhere else in the world: Grk.

Grk is a survivor from pre-phylloxera times, when there were likely dozens if not hundreds of minor varieties grown here in the Adriatic as everywhere else. After massive replanting of European vineyards in the late 19th century, most of these were phased out. Grk survived – just. Why it did remains a mystery, but it is partly due to the pure sandy soil of Lumbarda, which are not very well suited to other varieties (and do protect Grk from phylloxera, though to play safe, growers now graft it on American rootstock anyway). The challenge is that unlike 99% of other grape varieties that are hermaphroditic, Grk has female flowers only and needs another variety (Plavac Mali) to pollinate. Even with 30% Plavac in the vineyard, there is a lot of incomplete fruit setting, uneven ripeness on bunches, and yields are extremely low: one hectare will often produce just 1,000 bottles per year. It has long been theorised that Grk is the same as Italian Picolit or Hungarian Kéknyelű, but apparently latest DNA profiling shows there is no known relation to any other grape variety. A cultivar isolate, in a word, like the Basque language.

The other miracle of Grk is its taste. It is quite unlike most other white wines: salty. Mineral, pithy, citrusy, subtly floral too, but it mostly brings a taste of sea salt that at first, strikes you as an oddity. It also make it a fantastic seafood wine.

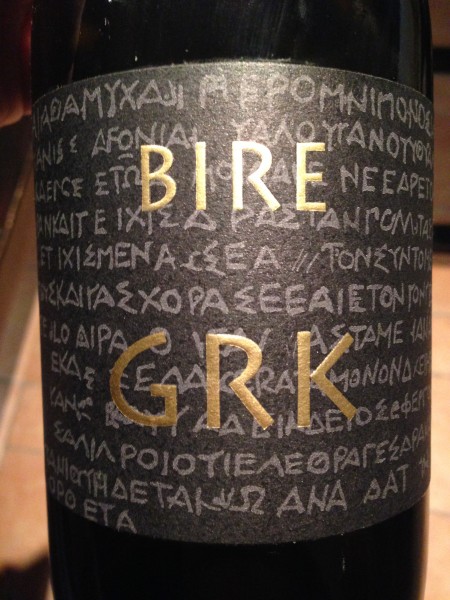

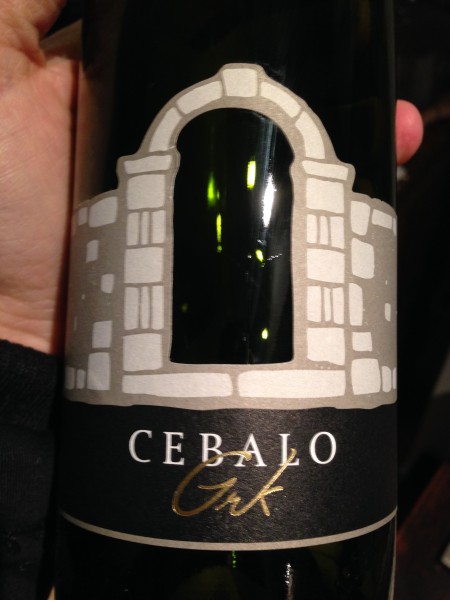

Two people can be credited for rescuing Grk from total abandon: Branimir Cebalo and Frano Milina Bire (there are six other growers in total). Our happy group of journos was hosted at the latter’s winery for a tasting and lunch. I had tasted these wines before, so knew what to expect, but they were captivating. Cebalo’s 2012 is rather soft and plush for Grk, avoiding the bitterness that is often the variety’s hallmark, but has plenty of minerality – and 13,9% alc. Bire’s Grk 2012 sees some short skin contact before pressing, is denser and fleshier but has a more pronounced bitter, alkaline character; a structured, engaging wine that proved great with food.

Frano Milina has now planted no less than 15 hectares with Grk outside Lumbarda, on the southern Adriatic slopes of Korčula, and looks to expand production in the next few years. I tasted some very exciting samples of the 2013 here, including oak-aged with malolactic fermentation that will be bottled separately under the name Grk Defora. This will add another, less pithy-mineral facet to Grk. After years of near-extinction, I was happy to see Lumbarda growers are now pushing Grk, notably organising a well-attended festival of the grape each spring. Apparently the entire production of Grk is sold out by the summer (it is really hard to find in any wine shops in Croatia). A second youth 2,000 years down the line?

Disclosure: my trip to the Croatia including flights, accommodation and wine tasting programme is sponsored by Zagreb Vino.com.