This gate in the old part of Lecce is a good metaphor of Negroamaro’s current condition.

Besides Primitivo (on which I’ve blogged here), Apulia’s other major grape variety is Negroamaro. It’s by far my preferred of these two. In many aspects, Negroamaro is the exact opposite of Primitivo. It ripens notoriously late, producing wines that are high in acidity and with nervy tannins but not very deeply coloured, with less sensual fruit than Primitivo. While Negroamaro can be harnessed to make some attractive unoaked, early-drinking, fruit-focused modern wines, its major interest in the past have been its ageworthy versions released after years of cask ageing, not in their primary youth but in the glory of their balsamic tertiary evolution. Aged Salice Salentino, the best appellation for this style of wine, as well as Brindisi, Copertino and several other DOCs have been, for me, some of the best wines of Italy’s Meridione.

I approached this trip to Apulia with excitement, therefore, but came back rather disappointed and worried. Old style Negroamaro is an endangered species. The ruthless modernisation of vineyards and cellar practice has swiftly relegated the traditional style to the antic. And there is a wave of Parkerized (or rather ‘Gambero-Rossoed’) Negroamaro that are really some of the most disgusting wines I’ve had of late.

The problem is that Negroamaro doesn’t really lend itself to modern vinification: it doesn’t like new oak, loses its vital freshness quickly when picked late in search of the elusive ‘physiological ripeness’, while its fierce tannins that formerly melted with years of large oak cask ageing, easily become exasperatedly drying when submitted to the Cotarella-style heavy-handed extraction. (Riccardo Cotarella is Italy’s most influential ‘flying winemaker’, and while long absent from Apulia he’s now consulting for some major wineries).

The Darth Vader of Apulia.

An eloquent example of Negroamaro’s collapse in the hand of the modern style was Leone de Castris’ Eloveni, supposedly an everyday easy-drinking example of the grape (which it was in the past), now overconcentrated and overextracted through some cellar tricks it’s better to ignore, and made to taste like a soupy ‘forest berries’-infused red that could with equal plausibility be a Colchagua Merlot or a Bulgarian Syrah. To cater for the alleged ‘consumer taste’ it even comes with a generous dollop of residual sugar, for which Mr. Cotarella has even coined a deliciously cynical euphemism of svinatura dolce (‘racking off while still sweet’: this clumsy translation does nothing to communicate the oxymoronic panache of the original). We’ve also had a series of revolting Negroamaros from youngly established wineries such as Antica Masseria del Sigillo, L’Astore, Menhir or Santa Maria del Morige.

New blood lacking, it were the old classics to solitarily defend Negroamaro’s honour. I was lucky enough to attend two mini-verticals of Apulia’s standard-bearers. Duca d’Aragona from the large winery of Candido is a blend of Negroamaro with 20% Montepulciano, aged in small oak. It’s a powerful red that needs plenty of bottle age to mellow, as shown by the tight, iron-cast, minty, aromatically still somewhat vague 2003, which I however trust will join the good vintages of this bottling: the purity of fruit and overall balance are quite fine (though my Apulian hosts dismissed it as ‘too international’; it’s now made by Lombardian consultant Donato Lanati). The 2000 is still too young, though slowly revealing the cherry core of real Negroamaro and its acidic drive, and taking on chocolatey, meaty notes of maturity; it’s another wine where the extract (not speaking of oak) is perfectly gauged, and impressively backward for 9 years of age. The 1998 (still made by Severino Garofano, the dean of Apulian winemakers) is brilliant, with a lovely complex nose full of green notes of mint and camphora, less solar, more mineral than the 2000 or 1997, with wonderfully preserved primary fruit and still some power to go. My preferred vintage was 1997 (my host Franco Ziliani preferred the 1998) that was lighter than the 1998 but had a supreme effortless elegance: fresh, poised, pure, tonic, delicate, still with a kiss of tannins, it was a majestic bottle.

Gratticciaia from Agricole Vallone was introduced in 1996 as an innovation: instead of softening Negroamaro’s rough edges with the soft fruity Malvasia Nera grape and long cask ageing, the grapes are given a few weeks of amarone-like drying on reed matts. The result is an individual, expressive wine with the pruney dried-fruity notes of an amarone but also the Mediterranean herby twist of Apulia. The 2004 (first vintage by new consultant Graziana Grassini) is just a little underwhelming at the moment, showing good depth and harmony on nose but rather simple and short on palate. The 2000 (which I’ve tried in Warsaw not Apulia) is tight, powerful, expressive and impressive but would best be kept for another 5–6 years. The 1998 is a great wine, with a lovely nose less driven by appassimento, flowery, mildly green too (a recurrent characteristic in this vintage), greatly long on palate, quiet, elegant, opening up nicely in the glass over 40 minutes or so, with fantastic firmness and poise on the finish. It can still go on.

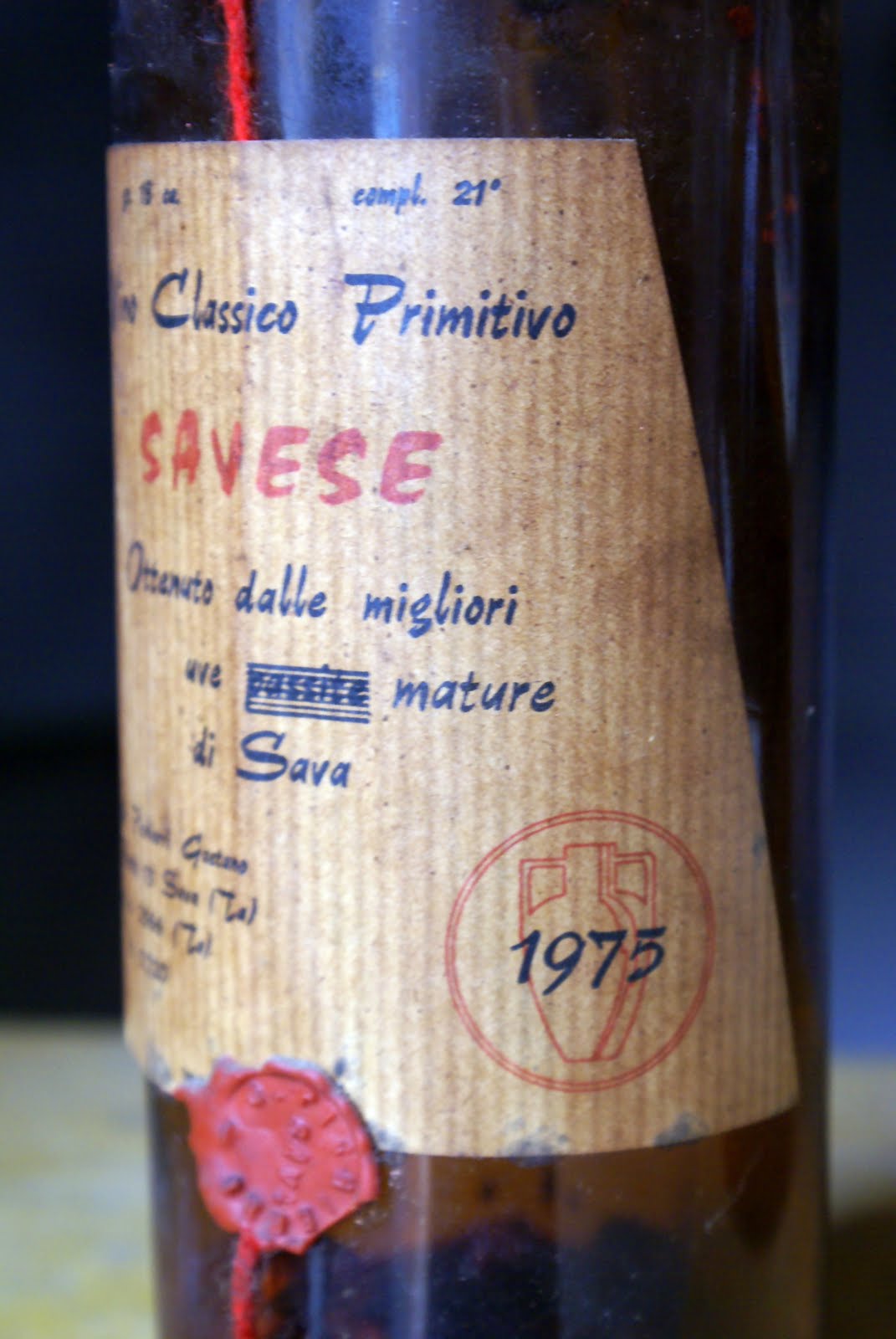

I have a weakness for the third of these Negroamaro musketeers: Patriglione from the Cosimo Taurino estate. Made from a lateish harvest but no drying of grapes, Patriglione comes from very old Negroamaro vines and sees some small oak which it digests very well. Here, too, a new winemaker has recently joined: Massimo Tripaldi, and his first vintage, the 2003, is very convincing with richness, power and structure to age well. I’ve recently also had the opportunity to taste the 2001 – more elegant than the 2003, with a textural finesse I found enticing; the slightly less convincing 2000; the 1994 that was a little tired (and had big cork problems with 2 out of 3 bottles tasted) but still showed the Patriglione character; the 1975 – actually the first vintage ever made: read here; and the 1997 which was a unforgettable bottle full of regal fruit, power and elegance at the same time. Patriglione is really a wine to die for, and at only 35€ it’s also quite affordable.