In Apulia (1): Neoprimitivism

Posted on 2 December 2009

I’m in Apulia, the Italian boot’s heel, to have a look at the current wine scene and the recent developments. The tour is organised by Radici Wines, an innovative mini-competition devoted exclusively to indigenous varieties, and my gracious cicerones are renowned wine writer Franco Ziliani and Enzo Scivetti of the Apulian branch of ONAV.

Fellow tasters Kyle Phillips, Rosemary George and Patricia Guy enjoying Pichierri’s Primitivos.

This lowland region is one of Italy’s largest producers of wine, although you’ll be excused for not being familiar with its produce as much of it is sold in bulk and much is of unexciting quality. In fact, Apulia conveys a sense of hopelessness as it has so far failed to create any romance associated with its wines. Sicily generally is jazzy and its Nero d’Avola wines just feel fashionable while Apulia, although its production structure is similar (co-ops, large latifunds, bulk production), is really stuck with its provincial image.

Well, there’s one wine that has managed to emerge from the Apulian magma of no less than 26 obscure wine appellations and as many grape varieties: Primitivo. This grape has been vehicled to fame by its discovered genetic link with Zinfandel and it’s been steadily gaining market share since.

Manduria’s period of prosperity was the 19th century.

Primitivo yields a controversial wine with massive colour, hyperintense fruit and limitless alcohol. While in the past high yields and conservative harvest times kept the wines within reasonable limits, the modern tendency towards higher concentration has generated wines that are absolutely outrageous. On this tour we’ve visited two Primitivo strongholds, Manduria on the Ionian coast next to Taranto, and the more obscure Gioia del Colle in central Apulia, and on both comparative tastings there were many wines above 15%. One of dry wines was 18.2% while several scored 16% with over 10g of residual sugar. More frighteningly still, Apulia still abides by the old Italian tradition of indicating total potential alcohol on the label (fractioned into svolto – the actual fermented alcohol – and non svolto which effectively is residual sugar). A Primitivo Dolce Naturale from producer Attanasio thus boasts 19.5% on the front label, while the off-dry and semi-sweet wines from veteran Pichierri are 19, 20 and even 21%.

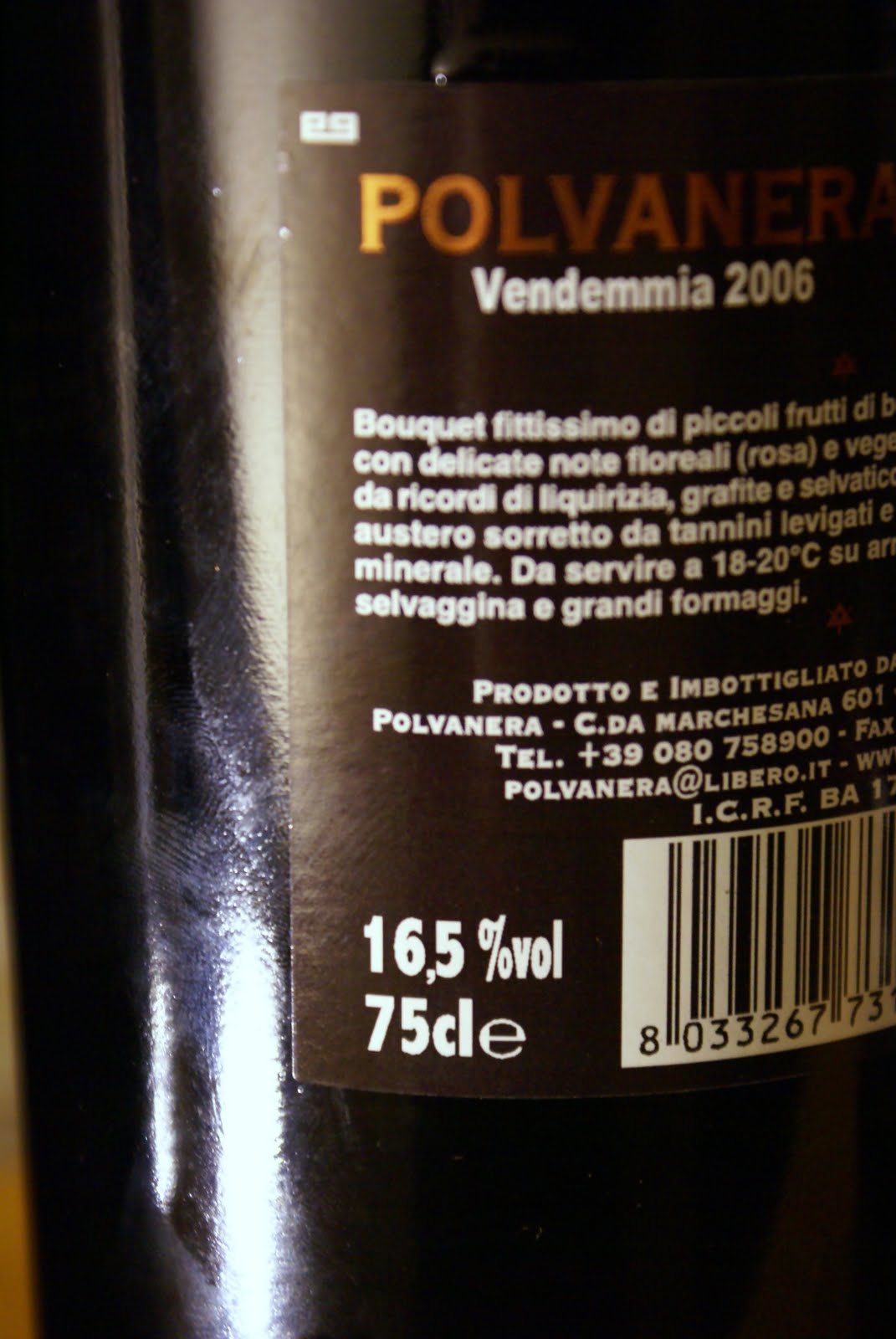

And this even isn’t Polvanera’s strongest wine.

For those port drinkers among you this might not sound all that outrageous but remember that half of a port’s 20% alc. is added in the form of grape spirit. Indeed the sweet Primitivos share many characteristics with port (and at the same time, amarone, being more often than not produced from slightly dried grapes) but have much better balanced alcohol. Semi-sweet red is a marginal style anyway. But the big problem comes with those 16 and 17% dry reds. If you agree that a wine’s primary characteristic is drinkability, Primitivo is born with a serious handicap.

It’s not the grape’s only problem. Naturally low acids and an obvious simplicity of bouquet are another. Combined with the modern tendency towards interventionist viticulture to increase concentration, late picking, heavy extraction, short ageing to boost primary fruit, and new French oak, all this results in Primitivos that are one-dimensional and really rather tiresome to drink. Sure, they have some of the most sensually compelling fruit profiles to be found anywhere, and when skillfully made can provide spectacular wines. Out of the 120-odd we’ve tried I’ve enjoyed those of Fatalone, Plantamura, scJ’o and recent star Polvanera (all from Gioia del Colle) as well as the very amaronish Attanasio, the superconcentrated Mille Una, the meatier, more rustic range of Accademia dei Racemi and the polished Duca Guarini. But a good half of those Primitivos were just too heavy, tiresome and barely drinkable.

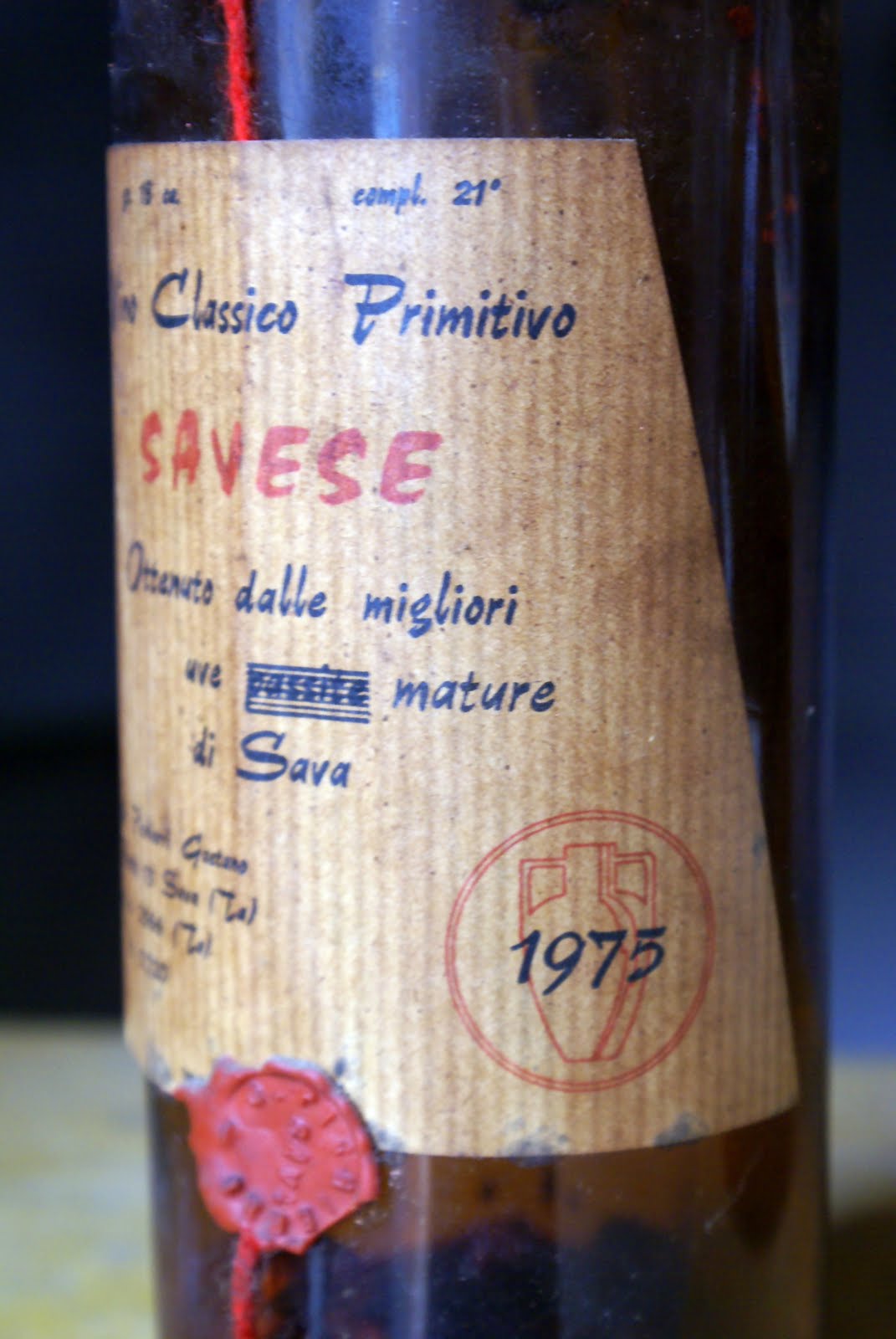

Vittorio Pichierri drawing 22-year-old Primitivo from clay amphora.

Although it can be argued that Primitivo as a grape can digest the modern style better than many (surely better than Apulia’s other main grape, Negroamaro), there’s something unique to traditionally-made old-style Primitivo that is sorely missing in the modern examples. A visit to the cellars of Pichierri in the town of Sava (formerly the heart of Primitivo cultivation) was an eye-opening revelation. Produced largely from bought-in grapes from free-growing old vines (alberello), slowly fermented in concrete tanks, largely unoaked, bottled several years after the harvest, and sold ridiculously cheap, Pichierri wines are unlike anything else I’ve tasted. Here, Primitivo reveals an unexpected depth of aroma, a compelling bitter chocolate texture that has nothing to do with the jammy flabbiness of the modern style, and the alcohol – although often even higher than its peers’ – is miraculously well balanced. Everything here is honest, wholesome and dangerously drinkable, from the basic 1.10€-a-liter bulk wine sold to locals in plastic containers (this is an important part of the business in Apulia, and most wineries we visited still sell a sizeable part of their production this way) to the trio of vini dolci naturali, unfortified semi-sweet Primitivos of wonderfully balsamic fruit and staggering expression.

The fun at Pichierri continued with the desealing of a traditional clay amphora called capasone, containing a 22-year-old Primitivo that was fresh as a daisy and deliciously juicy (if a little unclean and bretty), and then the 1975 Primitivo di Sava, one of the great wines of my life. 18% alcohol and a fair bit of sugar, black as ink after 34 of ageing (22 of which in tank), with a fabulously complex bouquet of grand cru chocolate, balsamic vinegar, dried fruits and Christmas spices, and a palate of such vibrancy and unadulterated, fleshy fruit that was beyond the reach of many vintage ports at age 10 and modern Primitivos at age 2.

Pichierri sell quite a bit on export markets and although largely ignored by the press and critics, they seem to be in good commercial shape. I truly hope they can continue to make Primitivo as they have for 30 years. When they stop, it’s one of Italy’s best kept classic secrets that dies out.

See another report on this visit by Franco Ziliani.