Anteprima Amarone

Anteprima Amarone: presenting the new vintage of Italy’s unique wine.

Anteprima Amarone: presenting the new vintage of Italy’s unique wine.

Photo highlights of my vineyard tour in Valpolicella and Verona.

Absenteeism is poisoning the Italian wine industry. Producers are shamelessly taking advantage of others.

Bertani enjoys a cult status in Valpolicella. A tasting of 1976 and 1967 Amarone shows why it’s fully justified.

Thoughts on the current condition of Amarone wine.

67 Amarones tasted, overall showing better than expected. And as always with blind tasting, some surprises.

A brilliant lunch in Verona, and what it says about the current economic mood.

Goodbye, Giuseppe Quintarelli. You will be remembered.

There’s still a lot of bad wine made under that name (drive from Verona to Vicenza and you’ll see hundreds of hectares under vine on the flat fertile clays by the railway line). Yet to dismiss Soave altogether would be a grave mistake. In fact, I consider it one of Italy’s leading appellations. This is thanks to some inherently great terroirs (predominantly volcanic tuff) and a generation of hard-working vintners that have elevated the DOC to its deserved glory: Suavia, Tamellini, Prà, Gini, Inama.

And then there is

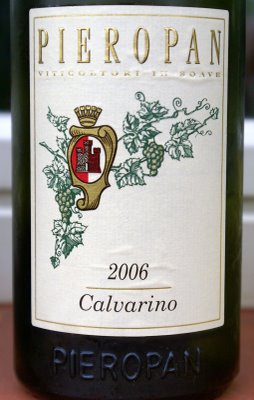

Leonildo Pieropan, Soave’s patriarch making brilliant wines since the 1970s. His Calvarino and La Rocca crus (the latter the first Soave to age in new French oak) are benchmarks for Italian white wine. It’s always intersting to try the old man’s new vintages, so I was happy to pull the corks from the two following bottles.The Soave Classico 2007 is, in short, a relative disappointment. It shows a vague Soave typicity of raw apple, diluted lemony crispness, and nominal reductive minerality, but it’s really a simple and unassuming creature. Same on the palate, juicy with no special length or depth. It remains a reliable wine, at least European-poised and refreshing and terroir-driven, but I just expect more fireworks from the name Pieropan on the label. It’s consistent with the latest vintages of this bottling: I think some new vineyards were introduced and the production increased, and perhaps this drop in stature and structure is inevitable until these new plantings grow older.

The Soave Classico Calvarino 2006, on the other hand, shows Pieropan in excellent shape. It drinks very well over three days and shows a real sense of place. Not overwhelmingly intense but has a strong mineral and acidic backbone that does wonders with food. Quite saline and active – this is real minerality, perhaps at the expensive of fruit which is much in the background (apple). Contrary to my expectations and despite coming from a warm, low-acid vintage this is everything but flabby. That’s clearly thanks to a 30% of the Trebbiano di Soave grape (the rest is Soave’s flagship grape, Gargànega), long despised for its low ripeness and aroma but now back in favour for the strong acidity (not to say greenness, as in this case) and minerality it lends to Soave wines. And it also lowers the alcohol – this wine is only 12.5%. An excellent bottle that needs a year or two more before peaking.

The Soave Classico Calvarino 2006, on the other hand, shows Pieropan in excellent shape. It drinks very well over three days and shows a real sense of place. Not overwhelmingly intense but has a strong mineral and acidic backbone that does wonders with food. Quite saline and active – this is real minerality, perhaps at the expensive of fruit which is much in the background (apple). Contrary to my expectations and despite coming from a warm, low-acid vintage this is everything but flabby. That’s clearly thanks to a 30% of the Trebbiano di Soave grape (the rest is Soave’s flagship grape, Gargànega), long despised for its low ripeness and aroma but now back in favour for the strong acidity (not to say greenness, as in this case) and minerality it lends to Soave wines. And it also lowers the alcohol – this wine is only 12.5%. An excellent bottle that needs a year or two more before peaking.

Went to a friend’s house recently to go through a shipment of samples he received from Gambellara, an appellation from the Italian region of Veneto that was recently awarded a DOCG status.

DOCG is supposed to be a notch above denominazione di origine controllata (DOC, Italy’s appellation of wine origin, equivalent to France’s AOC), although the exact difference is somewhat vague and the ‘G’ of garantita is hardly ever a guarantee of anything. There are currently 34 DOCGs in Italy including classic winemaking zones such as Barolo and Chianti Classico but also some rather puzzling nominations such as Albana di Romagna, an obscure and underperforming white wine zone east of Bologna.

Gambellara consists of 800 hectares of withered volcanic basalt located on extinct volcanoes between Verona and Vicenza in north-eastern Italy. Its whites wines – traditionally sweet passito from dried grapes, and now increasingly dry – are made of the Gargànega grape variety, and are in fact a lesser sibling of the better-known Soave, one of Italy’s classic whites made from exactly the same grape and on similar terroir.

I really, really like Soave and think it is one of the most underrated wines in Italy (today, thanks to the efforts of a dynamic group of vintners, it increasingly lives up to its potential). So I approached this tasting in a positive mood, but was vastly disappointed. We tasted 16 wines (10 dry, 6 sweet) that were all on a disastrously boring commercial level with no interest whatsoever.

Gargànega is not easy grape. It takes an expressive terroir and low yields to show good intensity, and the winemaking style needs to avoid extremes of technicity (bland ‘white-winey’ wines tasting like a million cool-vinified chardonnays or pinots) and oak (which can easily obscure the varietal character). On an everyday level, Gargànega can deliver a vaguely almondy, appley-crisp white with a hint of mineral salinity that is an unpretentious delight with lighter foods, but even that needs to be made properly.

These Gambellaras were simply mediocre. There wasn’t a single bottle I would remotely contemplate buying. They were thin, industrial, with a fair bit of SO2 reduction effectively masking whatever meagre fruit here might have been. There was no dream of terroir, and often not even of basic vinosity. There was so little body and such obvious underripeness in the dry wines it had me wondering what proportion of the 13% alcohol proudly displayed on labels was achieved with the forgiving participation of rectified grape must (Europe’s industrial wine chaptaliser / sweetener for those not in the know).

Even Gambellara’s best-known estate, Luigino Dal Maso, failed to deliver. One notable exception was the Gambellara Classico Prime Brume 2007 by the local co-op Cantina di Gambellara. Nothing great but what this wine should be: pleasantly almondy-bitterish fruit with a crisp, dry palate.

The sweet wines were, in a way, even more nonplussing. Apart from straight traditional passitos (named recioto here; it’s the wine that got the DOCG category from 2008) there were odd variations, including botrytis wines, and recioto spumante: sweet wines made from raisined grapes but given a secondary fermentation; so you have an odd crossing of Sauternes and Moscato d’Asti. The flavours don’t match (you don’t usually squeeze lemon on your peach jam?), the bubbles are as coarse as in Perrier mineral water, and the intellectual level is somewhere near kindergarten. I don’t even mention the other problems (volatility, dirty botrytis, reduction).

I don’t think Italy can find a writer more enthusiastic about its culture and wines than yours truly, but it really needs to work harder. Awarding the country’s highest level of wine certification to a bunch of mediocre stuff like this is surely going to alienate the public. Browsing Italian wine blogs it becomes obvious that the DOCG promotion for Gambellara was entirely a political move (the zone, together with neighbouring Soave, is home to some of Italy’s largest industrial wine producers) but from the consumer’s point of view, it’s an obvious scandal.