Tea on the move

Posted on 1 September 2009

I am back on the vineyard trail after several months of being confined at home. Together with erratic internet access, currency exchange and oversized hotel pillows frequent flying brings one major problem: how to drink tea?

Water is almost universally of poor quality and never at the right temperature; carrying fragile yixing teapots on economy class would be madness; there’s never room and time to properly brew – and pour – tea. Yet it’s impossible to do without. Unreasonable, too; as I travel to taste and drink wine, I often need increased hydration that can be efficiently supplied by some types of tea.

Water is almost universally of poor quality and never at the right temperature; carrying fragile yixing teapots on economy class would be madness; there’s never room and time to properly brew – and pour – tea. Yet it’s impossible to do without. Unreasonable, too; as I travel to taste and drink wine, I often need increased hydration that can be efficiently supplied by some types of tea.

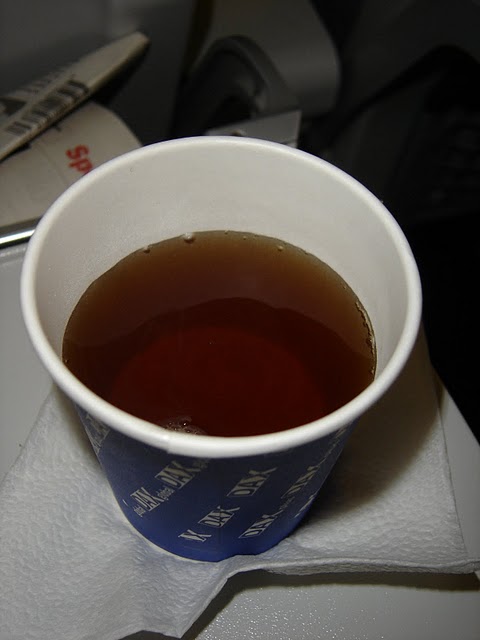

All tea lovers know that the quality of mass-produced tea is probably worse than any other food product. Industrial wine and branded coffee can be drinkable, but powdered tea in paper bags is one of the most execrable liquids you can put in your mouth. Flying Lufthansa last week, I was offered a paper cup of this:

The aroma was not all that bad, vaguely recalling some real-life teas such as shu [‘ripened’] puer in its mulchy, smokey, earthy edginess, but the mouthfeel was a total disaster. It tasted like a blend of shu and black tea, with a strong note of floating cadaver. (I later found out this tea-like product is supplied by Eilles and brewed on board in large plastic containers).

The aroma was not all that bad, vaguely recalling some real-life teas such as shu [‘ripened’] puer in its mulchy, smokey, earthy edginess, but the mouthfeel was a total disaster. It tasted like a blend of shu and black tea, with a strong note of floating cadaver. (I later found out this tea-like product is supplied by Eilles and brewed on board in large plastic containers).

So we tea lovers need to find a way to brew our own tea while on the move. There are two critical issues: the type of tea and how you brew it. Starting with the latter, I’m strongly advising single-vessel brewing: you put leaves and water into a largish cup and drink from it. I know some people carry a gaiwan or even a clay pot but I find this to be OK for comfortable hotels stays (where you can expect some kind of tea service anyway); pouring hot liquid from a gaiwan on an airplane seat is not a great idea. You could of course just carry your tea leaves and infuse them in the paper or plastic cups that are available everywhere, but I find paper to give an unpleasant dryness to the tea, plus a disposable cup will cool down rather quickly and the tea will almost always be underinfused:

My choice is for a cylindrical 150ml cup made of thick porcelain (retains heat well) with a loose-fitting lid. This piece is both solid and functional and thanks to its shape, drinking is easier than from a wide-mouth gaiwan:

Type of tea: in my experience, this needs to satisfy two criteria. It needs to withstand long infusion times (using a cup like the above, you cannot drain tea into another cup so leaves continue to infuse as you drink). And it needs to brew properly with water at less than boiling temperature. Point 1 effectively eliminates black tea (becomes too tannic), Japanese greens (too bitter) and puer (too bitter, unless it’s old, but even then prolonged brewing times will hardly do the tea justice). Point 2 eliminates puer (needs boiling water) and some types of oolong: while you could insist on having Wuyi oolong, I find they really need very hot water to brew properly. On a plane, at a train station, even at a hotel’s buffet breakfast water is more often around the 85–90C mark.

Type of tea: in my experience, this needs to satisfy two criteria. It needs to withstand long infusion times (using a cup like the above, you cannot drain tea into another cup so leaves continue to infuse as you drink). And it needs to brew properly with water at less than boiling temperature. Point 1 effectively eliminates black tea (becomes too tannic), Japanese greens (too bitter) and puer (too bitter, unless it’s old, but even then prolonged brewing times will hardly do the tea justice). Point 2 eliminates puer (needs boiling water) and some types of oolong: while you could insist on having Wuyi oolong, I find they really need very hot water to brew properly. On a plane, at a train station, even at a hotel’s buffet breakfast water is more often around the 85–90C mark.

This leaves us with a couple of tea types that can do a good job in the circumstances. Taiwanese Baozhong is one: lower water temperature is OK and brings the tea’s floral aromas to the fore, and it can happily be brewed with little leaf and long infusions. The drawback is that Baozhong leaves take a lot of room and are fragile, so packing them in bags results in leaf breakage, and if you’re travelling for a week or so, your supply of tea will require a largish jar / can that is impractical to pack. For this reason, I prefer to carry rolled oolongs such as Anxi from China or gaoshan from Taiwan. On the picture below, it’s the 2008 Competition Grade Maoxie (see review here) brewing: just seven or eight tea ‘balls’ into the pot and water from the Boeing 737 hot water dispenser. Put the lid on and wait for two or three minutes. Afterwards I start sipping, but the leaves continue to infuse for another five minutes or so. The resulting tea is less delicate and floral-driven than a gongfu-styled brewing of the same tea, with a more pronounced vegetality and a bit of dryness at end. However, it remains a very refreshing tea with good texture.

Taiwanese high mountain oolong will result in a creamier, richer cup. An unroasted Shanlinshi, for example (such as this one), will echo the leafy notes of the Maoxie but will be subtler. You can also introduce an element of roast for a grainier, less vegetal tea: try this high-roast Shanlinshi for example.

I often carry two or three different teas while travelling. Being able to brew your own top-quality stuff and forget the Lufthansa plonk is a luxurious feeling.