Sky is the limit

Posted on 26 August 2011

I rarely blog about one of my favourite products: olive oil (Here’s my recent try). I’m not a trained taster of oil (and it takes a lot of training to be good at that), and the flavours and profiles of extra virgin olive oil are elusive: it’s difficult to put your impressions into words. More so than with wine and tea, I reckon. (Marco Oreggia is an EVOO taster that’s doing a good job at making it easier).

There are some very impressive olive oils around, however. One exciting development is the Olio Secondo Veronelli project. Luigi Veronelli was an leading wine and food writer (see bio here); he’s influenced the development of Italian wine more than anybody else in the last century. Less well-known is his work on food, but the manifesto he coined in 2001 has revolutionised olive oil production.

In very short summary Veronelli’s ultra-qualitative approach advocated total control over the cultivation and processing of olives. Oil is cheap (around 1€/liter on the bulk market), and it lacks the financial incentive for producers to invest in quality. Things such as planned plantings, selecting olive varieties, processing the fruit within hours of the harvest, and extracting and bottling oil with the use of latest technology were economically unviable until recently. As specialist oil has garnered some (though not enough) attention from critics and consumers, willing to pay 15 to 25€ per bottle of oil, some growers in Italy and beyond started exploring and crossing the boundaries of quality.

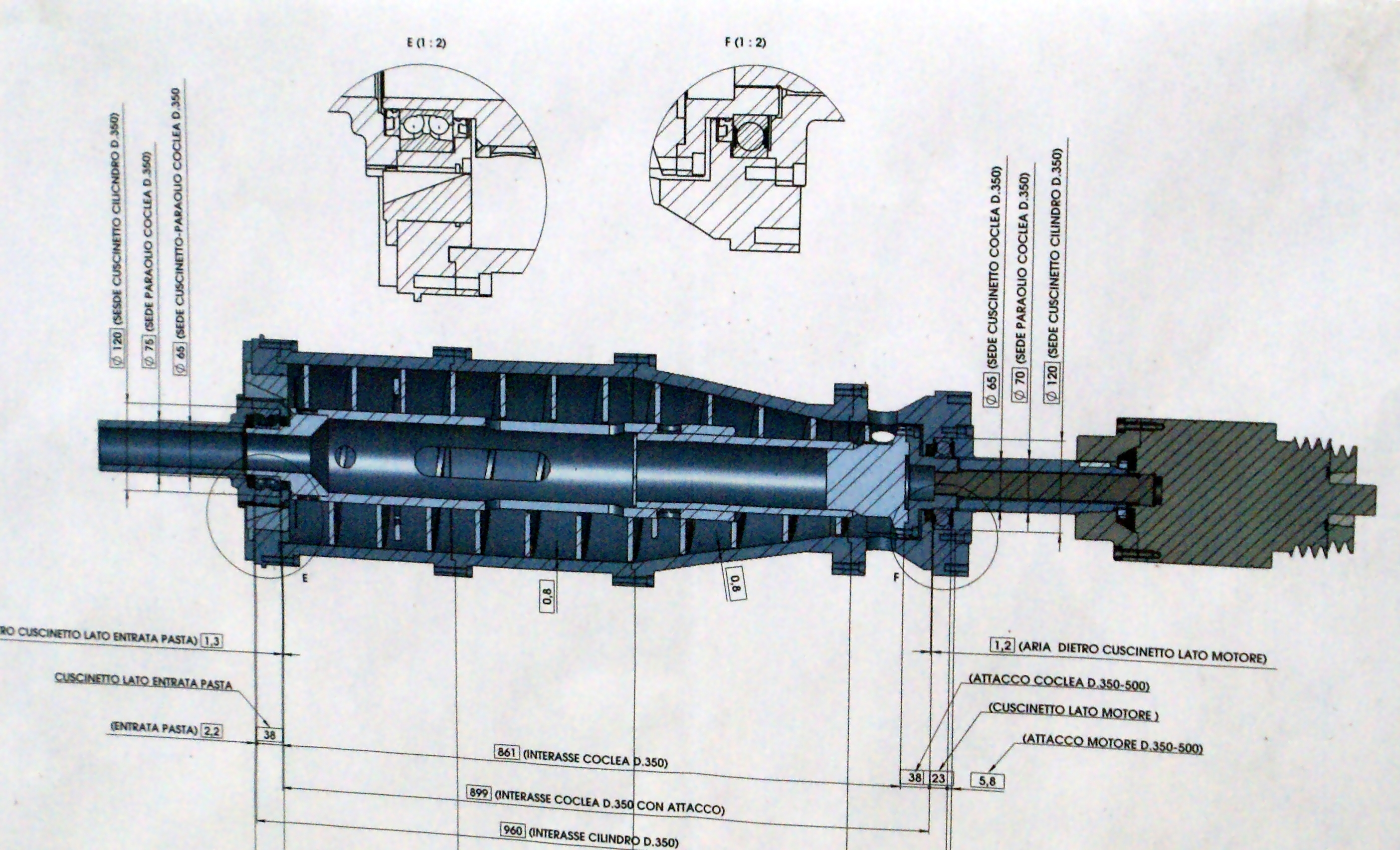

The olive press at Comincioli consists of 500 parts and needs to be disassembled after each pressing.

The Olio Secondo Veronelli project currently gathers a dozen producers including Fèlsina in Tuscany (other than my favourite wines, perhaps the best EVOOs I’ve ever sampled), Terre di Balbia in Calabria, and Planeta in Sicily. The Veronelli Manifesto outlines the technical premises for oils to receive the prestigious OSV trademark: all trees are catalogued, all olives are 100% traceable, chemical weed killers are forbidden, olives are harvested in 20kg boxes, olives must be washed with drinkable water. But most importantly all olives are pitted. This crucial innovation reduces the oil’s acidity and bitterness by allowing to produce oil in a completely reductive, oxygen-free environment. With the pits in, olives need to be crushed in a mill, and there’s always a bit of oxidation resulting. The denocciolamento allows for the making of a soft olive pulp that is subsequently extracted in a vacuum stainless steel press; stabilisation and bottling are also done under a blanket of neutral gas and the oil never sees any oxygen until you open the bottle. This pushes the best before date by an extra year (normal EVOO should be consumed within year, though see here for the ageability of oil). It also boosts the polyphenolic content of EVOO.

I admired all this, and more, at the Comincioli winery & olive mill on the Lake Garda in Italy. Gianfranco Comincioli is one of the most ambitious producers working hard to elevate the Garda DOC from its current position as a provider of anonymous holiday wines. His several takes on the indigenous Groppello grape are fascinating, as is the skin-contact white Perlí. His Diamante rosé might well be the best wine of that colour I’ve ever tasted: deeply coloured, minerally refreshing, it just explodes with layers of sensual fruity and flowery flavours on the palate.

Comincioli’s greatest ambition, however, is olive oil. By investing thousands of € into quality he has rocketed into EVOO fame, scooping awards every year for his cutting-edge pitted oils. Olive trees occupy about 10 ha here on the soft morenic gravelly hills on Lake Garda’s western shore, the same surface as vineyards: Gianfranco’s success can also be seen in 39% of the estate’s revenue being generated by EVOO today (normally from a similar surface, it would be closer to 10%).

No expense is spared and no technical innovation is neglected in reaching for the sky. Olive trees are trained in the revolutionary monocone shape, facilitating mechanical picking of olives by custom-design harvesters. Normally, olives are picked by hand, but a skilled worked can only do 100 kg of fruit in a working day, whereas a machine can do 3000 kg: since time is crucial in picking olives, using machines allows to get the whole crop in a couple of days.

Less than an hour elapses before washed and sorted olives are put into a space-technology olive press where they are pitted, ground and softly extracted under a blanket of inert gas before being transfered to stainless steel vats for stabilisation. From olive to vat, the entire process takes 80 minutes. Loss of quality is thus minimised, resulting in an incredible richness of flavour. Comincioli’s top oil, the 2009 single-cultivar Casaliva, topped 617mg/l of polyphenols which is Italy’s and perhaps Europe’s record. (A good regular oil is between 100 and 150mg; Olio Secondo Veronelli is usually >300). Gianfranco is confident that more can be done. “Olives have about 2000mg of polyphenols, so even with the inevitable loss during processing, we might still get around 1000mg into the bottle if we improve our process further”. He is currently looking at actually lengthening the extraction so that processing is more delicate.

Unforgettable: Comincioli Casaliva 2009. © Comincioli.

In one of the most memorable sittings of my life as a taster we were served three Olios Secondo Veronelli from the 2009 vintage. The Leccino, from a cultivar you’ll find all over Italy including Tuscany, is a piquant, peppery oil that however has a caressing sweet texture with amazing length. The N. 1, a blend of a dozen traditional Garda Lake varieties of olives including the ultra-rare Trepp, Favaröl, Cornaröl, and Rossanelis is more assertive and complete, with fabulous intensity and a roaring progression on the palate. Depitted oils lack the often violent bitterness and mild oxidative nuttines of regular oils, but are also more multi-dimensional, and much longer on the palate. It’s like oil on a good stereo: not always better music than from a scratchy LP but so much more vivid and spatial. Finally, the 2009 Casaliva (a local variety of olive from the Garda) has the elegance of the Leccino and the fullness of the N. 1. Artichoke, tomato and bay leaf, spinach, vanilla, almonds, pine nuts, green peppercorn, finishing almost tulipy… It has to be tasted to be believed.

It might have cost Gianfranco Comincioli €1m to get there (though the Casaliva itself is more than reasonable at 22€ per 500ml bottle) but he now stands where no man has stood before: on the Mt. Everest of olive oil.

Disclosure

I travelled to the Garda in September 2010 on the invitation of the Garda consortium of wine producers who sponsored my flights, transfers, accommodation and wine tasting programme. Bottle of 2009 Casaliva EVOO to retaste at home kindly offered by Gianfranco Comincioli.