Giuseppe Quintarelli dies

Posted on 16 January 2012

Sad news today, communicated by Franco Ziliani. Giuseppe Quintarelli, patriarch and champion of Valpolicella and Amarone, passed away on Sunday at the tender age of 84.

I first met Quintarelli in 2002. A novice writer at the time, visiting the Great Man was something of a pilgrimage for me. I remember it involved hitchhiking from Verona and then a longish climb until an unsigned cypress-lined alley diverted from the local road, leading to an unassuming country house that didn’t betray the large cellar and treasure nest lying underneath. Quintarelli himself greeted me, showing me around the cellar with its imposing old Slavonian oak casks and thousands of bottles ageing before he deemed them ready for release (which seemed ages; even his Valpolicella went on sale after seven years). He was not a heart-on-his-sleeve kind of man, and I felt a bit of an examined schoolboy as we sat down on a wooden bench to taste the wines. I remember it was my familiarity with the Saorin grape that broke the ice eventually: Quintarelli was very fond of this rare local variety that he revived (albeit in minute proportions) in his tellingly named Bianco Secco.

Tasting at Quintarelli’s always followed the same regime that never changed in the number of visits that I made there over the years. All wines were standing there in opened bottles for what likely was weeks; there was never question of opening a new bottle before the old one was finished. I remember visiting with an English wine writer who later said he thought all the wines were oxidised and awful. Were they? It wasn’t my feeling, even if the Valpolicella and Amarone were tasted a month after opening. Their elemental power was laid even barer for the drinker to appreciate. Tasting was always in minuscule ISO glasses and I was strictly told ‘no’ to the large Schott-Zwiesel glass I usually carry on my trips. There was no talking, just sipping, until the drinker was ready to summarise his or her feelings, to which Quintarelli would nod approvingly. But vinification and other technical details were uninteresting topics. Tradition and history, more so, and his insights into how Valpolicella grew from the forgotten backwater to what it is now were fascinating.

Quintarelli was uncompromising as a person and as a winemaker. Although firmly of the Old School, he did introduce new things, growing quite some Cabernet and Merlot in the vineyards and even using small barrique oak in Alzero, his stunning reinterpretation of Amarone. But quality was a condition sine qua non. Never was substandard fruit allowed into any of his wines, and even the entry-level Primofiore showed a level of quality beyond the reach of many wineries in the region. Although he sometimes was criticised for this forceful, superconcentrated style (the Valpolicella here was little else than a baby Amarone), nobody could deny Quintarelli’s absolute commitment to wine quality and the tradition of his region.

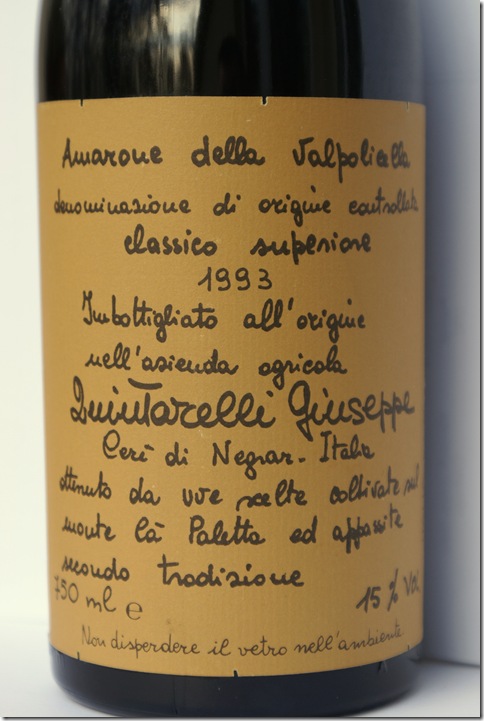

I have been blessed to taste many of his creations, including the 1995 Valpolicella that is easily the best that I’ve ever has, and more recently an epic bottle of 1993 Amarone. And that is even without mentioning his legendary (and excruciatingly expensive) Riservas.

He will be remembered.