Roero: the third twin

Posted on 31 May 2013

Being the third child is never easy. Especially when your two elder brothers are geniuses. But that’s the life of Roero, a small wine appellation in Piedmont that lies next to Barolo and Barbaresco.

Barolo & Barbaresco together form a district known as Langhe. Roero technically is distinct from Langhe, but it is too small to be thought of as a separate entity. And so in an act of courage Roero has joined the annual presentation of new Barolo and Barbaresco vintages known as Nebbiolo Prima. This has been my primary opportunity for tasting the majority of its wines, year after year. The progresses have been staggering: there were maybe six or seven interesting producers a decade ago, now there are three times as many. And the wines seem to have it all: quality, honest prices, a distinct personality, nuances of difference between producer styles and microareas. The worst thing you can do to Roero is to taste alongside a Barbaresco and a Barolo: this can only reinforce the perennial third twin stereotype.

All equal, all different

It is unfair to compare them in the first place. Those three zones lie side to side and they use the same grape variety: Nebbiolo. But it’s pretty much where similarities end. Roero lies on the northern bank of the Tanaro river, on light, fresh soils – predominantly sand – that give the wines a crisper, more immediate appeal than the brooding sweet cherry fruits of Barolo, for example. The slightly more northern position gives a different microclimate, too, as do the very steep slopes you encounter here: while the renowned crus of Barolo such as Cannubi, Brunate or Bussia are well-exposed but reasonably soft hills, some of the vineyards in Roero are almost vertical. Much harder to work, of course, with very limited mechanisation; but nobody said it would ever be easier for the third twin.

Roero has been on a roll of late. The qualitative ascent of the entire district has been largely enabled by one simple thing: money. Vintners have cashed in thanks to the soaring popularity of Arneis, a white wine grown almost exclusively in Roero, that has become Italy’s urban favourite in the last decade. Traditionally Arneis was a rustic, often charmless wine marred by a heavily bitter finish; it worked decently well with the local cuisine (try it with carne cruda, the local version of beef tartare; it’s a delight) but didn’t have assets to move on. It was with modern techniques such as cool fermentation, leaving a dollop of residual sugar and/or CO2, and launching popular brands such as Ceretto’s Blangé that Arneis really took off. Ceretto now make 600K bottles of Blangé (that’s 15% of all Arneis sold around the world), fuelled by the insatiable Italian appetite for “aperitivo” which this wine suits so well, and other producers have followed.

Apples or pears?

I really love Arneis, and I think it has more facets than the simple aperitif bland-ish white. It can do that well, granted: a light body, transparent citrusy and peary flavours, supported by that bitterish pithy signature that makes Arneis such a great second-glass wine. Giovanni Almondo makes an Arneis like this, as do Matteo Correggia, Vietti and Malvirà. In Bruno Giacosa’s bottling, the first Arneis many people will taste because of the producer’s notoriety, there is more oomph, and the flavours veer toward apples and peaches; it’s a style you’ll also find in the likes of Cornarea.

But Arneis can be like Riesling, too. It’s a comparison that inevitably comes to mind whenever I taste the impressive Inprimis from Ghiomo. Giuseppino Anfossi (see my profile of this overperforming producer) bottles this wine as DOC Langhe Arneis because his vineyards are on the wrong side of the hill but this could well be the best white wine in Roero: limpid, mineral, sleek and refreshing, it has the electrifying acidity of a good Rheingau or Nahe Riesling. This year, we looked at a mini-vertical of Inprimis from 2011 (bursting with delicious crisp fruits) to 2008 (slowly ageing towards honey and toast, but having no less than 7g acids, it will go on for years). And Arneis can age like a good Chablis, too. I reported here on the staggering vertical tasting organised by Angelo Negro where we went back to Arneis Perdaudin 2001: well alive with fantastic dimension, it showed the real, hidden potential of Arneis.

But Roero is at heart a red wine region. The relative affluence brought in by Arneis also helped develop the reds. And the district’s moment of glory came in 2004 when after years of effort, the area was granted the DOCG, Italy’s highest appellation status, effectively putting it on the same level as Barbaresco and Barolo. Well, at least bureaucratically, because the top bottlings of Roero Riserva DOCG usually sell for 15–25€, which is half the price of Barolo and some 25% less than Barbaresco. But producers I spoke to this year were unanimous in their appraisal for the move: it has improved the image of Roero and helped spread the word. There are surely some very good wines made under that category. From my tastings this year, I really liked the 2009 Giovanni Almondo and Cascina Chicco Valmaggiore. In past vintages, including the cooler 2008, I’ve also liked the Malvirà Trinità, Michele Taliano Ròche dřa Bòssořa (no typo here, these are the Piedmontese dialect diacritics), Monchiero Carbone Printi, and two quickly improving producers are Cascina Ca’ Rossa and Daniele Pelassa.

Trying too hard?

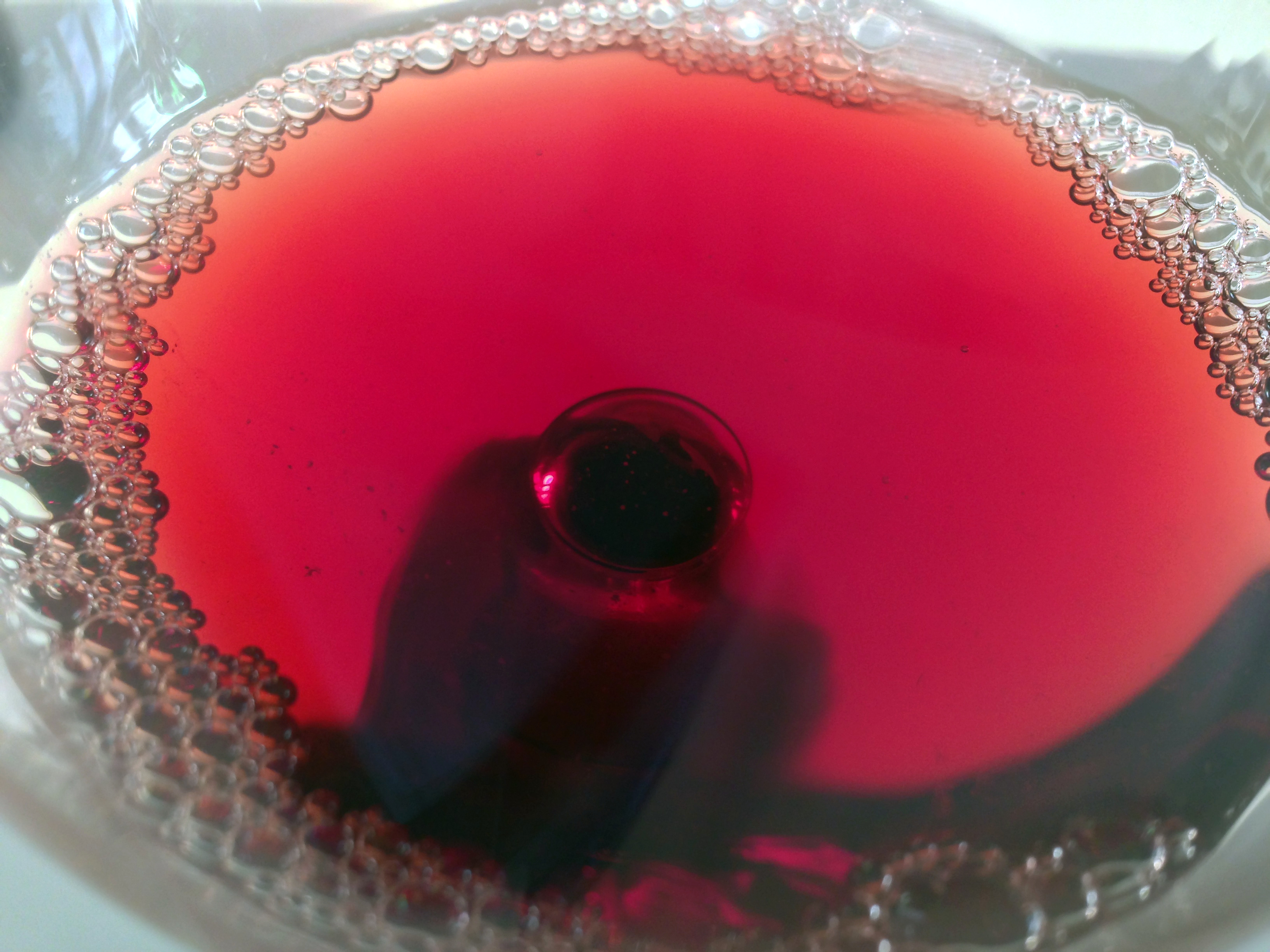

These are all fine wines, rich and structured with plenty of tannic backbone – more so than in your classic Barbaresco, I feel – offering a good 10-year window of drinkability. Actually you could argue some are too structured: overextraction has been a problem for years. Wood, too – although curiously Roero seems to take new oak better than some Barolos, there is always a question of whether Nebbiolo really needs it. The paradox of the Roero Riserva DOCG is that on one hand, it undeniably gives credit to an area that deserves it, but on the other, it puts emphasis on heavier wines. (Admittedly many of the latter come from pockets of heavier, more suitable clay soils). Italians call them importante, and that mild obsession with “importance” (which really means “extract”) is a very Italianate phenomenon. I for one often prefer a producer’s simple Roero. Usually made unoaked (which Barbaresco or Barolo cannot be), such versions really take advantage of Roero’s lighter sandy soils and offer a wonderfully elegant, drinkable interpretation of Nebbiolo. Just look at the delightful rose petal colour of the Malvirà Roero 2009, or taste the lip-smacking cherry vibrancy of Ca’ Rossa’s Audinaggio. These bottlings might be less “importante” but I actually find them more representative of Roero, its wine tradition and identity.

As mentioned, Roero as a wine zone is currently on the upswing. But there are still issues to be resolved. One is a stronger emphasis on Roero as a brand. There needs to be concerted effort by all vintners operating in the area. The unfortunate situation at the moment is that producers can opt for their wines to be labelled as Roero but also as DOC Nebbiolo d’Alba or Langhe Nebbiolo. The latter two have the advantage of printing Nebbiolo on the label, which some argue is better known internationally and domestically than Roero. They might be right, but that is precisely why everybody needs to work to make Roero more notorious. Others, e.g. Renato Ratti, say they were historically labelling their wines made from this area as Nebbiolo d’Alba long before Roero became a DOC. True again, but a household name like Matteo Correggia, whose Ròche d’Ampsèj has for years been the most impressive and coveted red wine to originate from Roero, has now moved it to the DOCG Roero Riserva category. Others should follow his example but not all do. Is it because many producers of Roero wine have their HQ elsewhere, in Barolo and Barbaresco, and so feel no imperative to promote Roero as a brand?

Straddling the grand cru

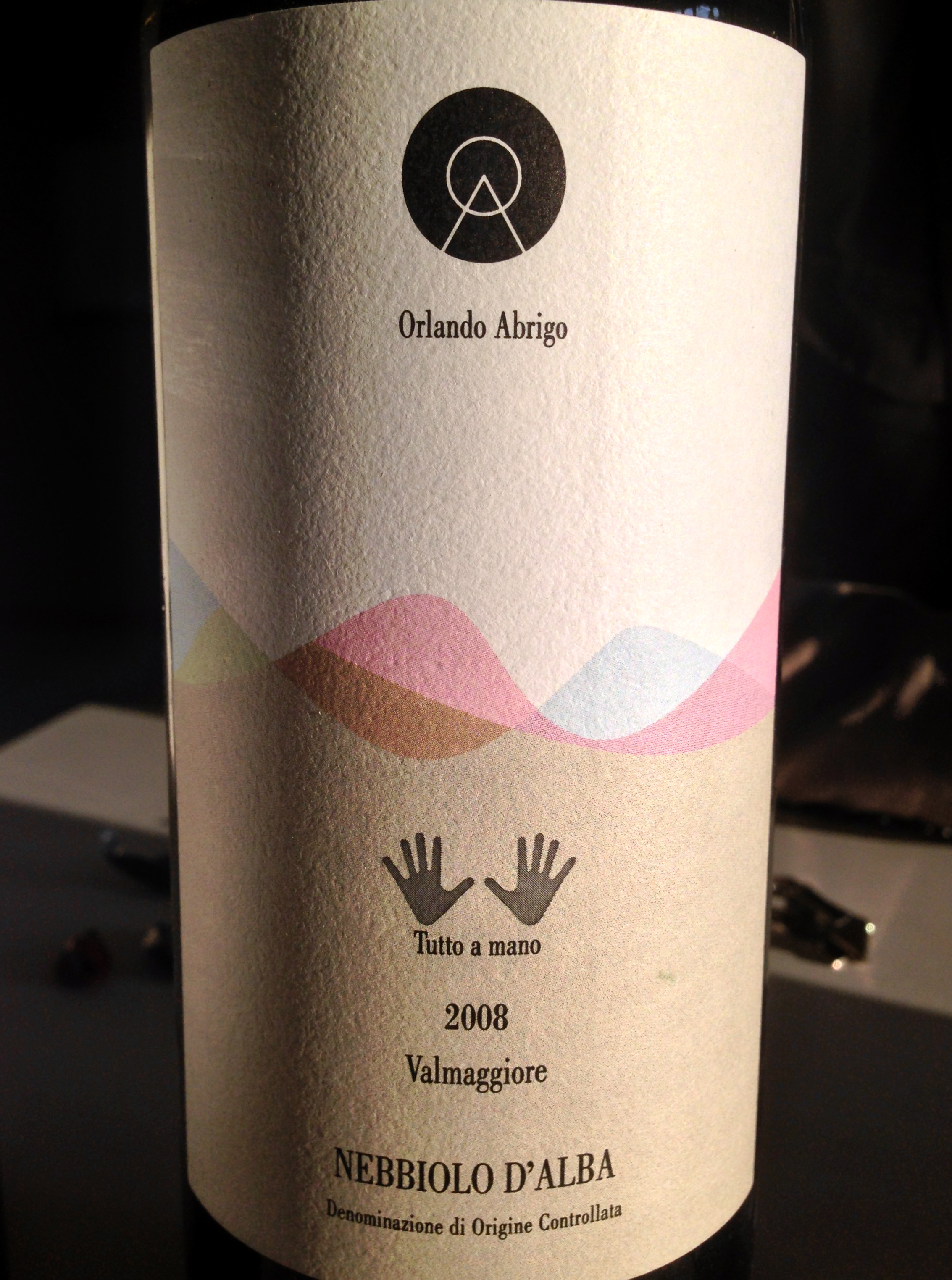

Two most famous Roero single vineyards which have long been bottled as Nebbiolo d’Alba are Occhetti and Valmaggiore. I visited Valmaggiore with vintner Gianni Abrigo of the Orlando Abrigo winery (himself a producer of excellent Barbaresco). And after years of tasting hundreds of Roero wines, it is only here, climbing at 340 meters of altitude and looking down on those impossibly steep slopes, that I finally appreciated the true identity of Roero. Valmaggiore is the northernmost grand cru for Nebbiolo in this macroarea, and lies on the lightest soil too: eroded marine Plyocenic sand. Rainwater flows through it like a sieve; heavier precipitations can simple wash down an entire slope, as happened in 2009.

Gianni Abrigo reinforced his vineyards with microterraces but the manual work of tending those vines remains very tough (700 hours per hectare per year). When we visited, spring was quite late but vines were avidly spreading their green shoots around; butterflies and bees wandered through the vineyard and in the distance, we spotted a hare. There are bits of forest around, and wild boars can be a problem. For a moment it felt incredibly remote and tranquil, though the vistas of the surrounding crus reminded us we were in the Gotha of Nebbiolo.

Valmaggiore has been made famous by Bruno Giacosa and Luciano Sandrone. The latter’s wine (from 2.7 ha; the product page has good information on the vineyard) is made as a baby Barolo in Sandrone’s forceful style, dark as ink with big concentration and attractive black fruits on the palate. It ages beautifully, too, and I’ve tasted some impressive bottles even from derided vintages such as 2002.

There are other Valmaggiore bottlings now including from Cascina Chicco (year in year out this is one of my favourite Roeros), Fratelli Pezzuto, Battaglio, Eugenio Bocchino, Brovia, Cascina Bruni, Giacomo Grimaldi and Mario Marengo (tellingly and unfortunately, only the first two are labelled as Roero; the others are Nebbiolo d’Alba). Back at the Abrigo winery with Gianni, we opened a bottle of his 2008 Valmaggiore. In the glass was the most incredible light rose petal colour, lighter than many a rosé these days, with an ethereal nose of wild forest fruits and spring flowers. The lightness carried on the palate, deceptively so because the crunchy tannins were surely those of structured Nebbiolo.

I felt magically transported to the vineyard again, its natural serenity and the sandy soils full of sea creatures from 5 million years ago. “The colour of rosé, the acidity of white wine, and the tannins of red”: this was Nebbiolo in its purest form. And Valmaggiore, Roero’s grandest vineyard, was there to tell its true story.

Disclosure: my trip to Piedmont including flights, accommodation and wine tasting programme was sponsored by the Albeisa association of local wine producers.