2008 Jirisan Woojun

After yesterday’s post on a tea from Korea here’s another one. This 2008 Woojun (alternate spelling of ujeon, the top grade / earliest picking of Korean tea) from the Jirisan mountain is also from Eastteas. Unlike yesterday’s Nokcha, this tea is fairly expensive (£65 / 100g) but I would gladly pay double the price.

After yesterday’s post on a tea from Korea here’s another one. This 2008 Woojun (alternate spelling of ujeon, the top grade / earliest picking of Korean tea) from the Jirisan mountain is also from Eastteas. Unlike yesterday’s Nokcha, this tea is fairly expensive (£65 / 100g) but I would gladly pay double the price.

When buying Chinese tea, the earliest April flush (pre-qingming) is a reasonable standard of what you should seek and accept. Unless you’re late with your shopping and the spring teas are sold out there’s usually no problem in sourcing pre-qing stuff, and it needn’t be extravagantly expensive. At least for me, it is a good ‘normal’ grade.

Korean ujeon (which technically is the same) is a different story. Due to very low production (it makes up a fraction of Korea’s insignificant 1500 tons of annual yield) and high demand it’s a rare grade, and can get frightfully expensive. On the positive side, the quality is usually spectacular. This sample surely is.

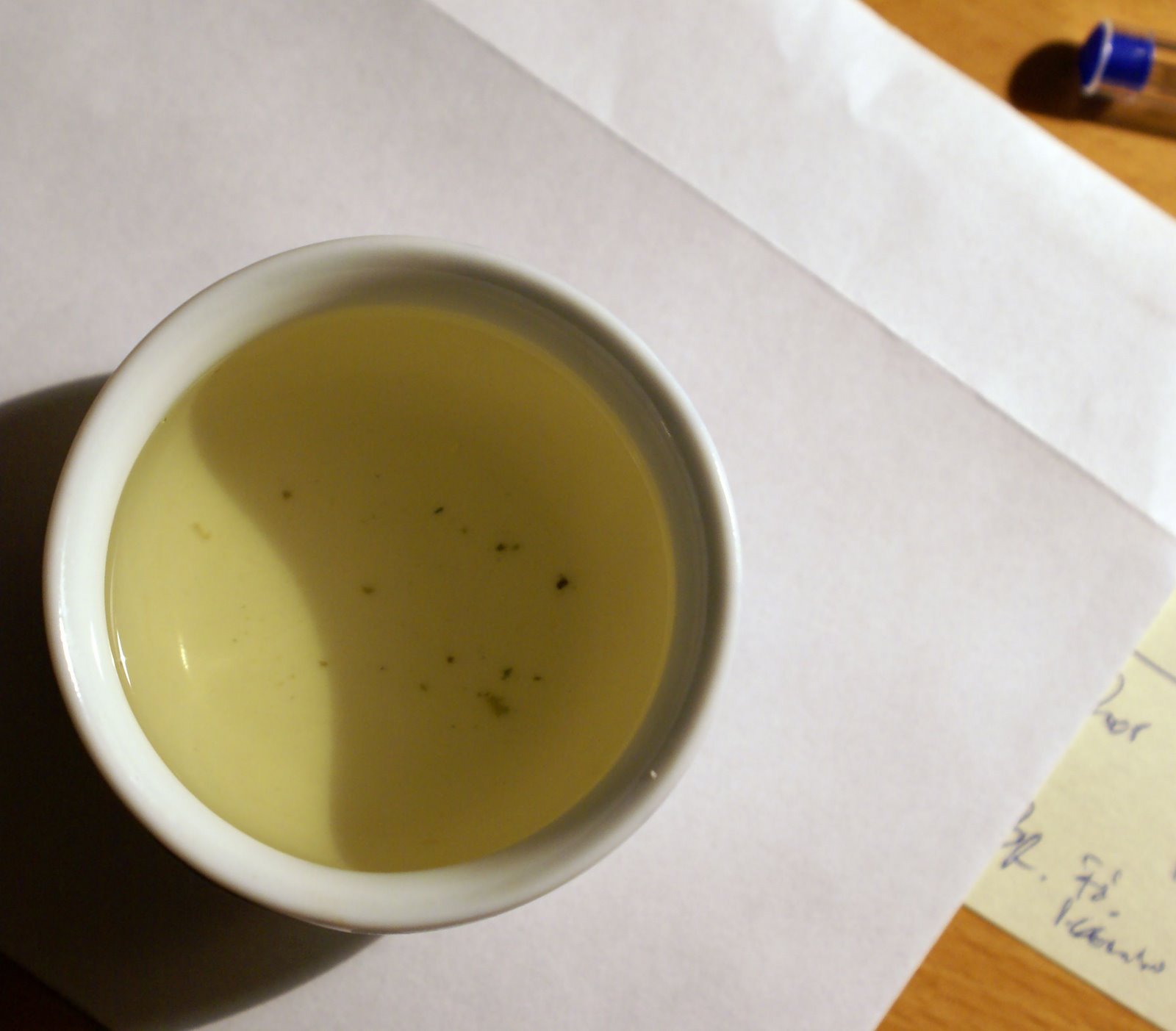

Infusion no. 1 (45 seconds).

I have formerly enjoyed the Sparrow’s Tongue offering from Eastteas (colonial translation of jaksol or chaksol = sparrow’s tongue, a blanket term for green tea that can range in grade from ujeon through sejak down to jungjak), finding it superlatively intense and defined, and when Alex Fraser said Woojun is even better, deeper, and more intense, I was incredulous. And yet…

The leaves are really tiny (while perfectly intact). If you want to see how tiny, scroll down to the last image of this post. They indeed look like sparrow tongues or very tiny curly needles. Importantly, the dry leaf aroma is superb. It shows a very intense, distinctly herbal character I identify as oregano, with top notes of supergrade Italian olive oil. One of the best-smelling teas in my memory.

Brewing is a tricky affair. Alex Fraser recommends high dosage, low temperature and short infusions. Surely you should step down even to 50–55C for your first brewing; dosage is a matter of how you like your green tea. Using 5–6g per 100ml and lukewarm water you obtain something along the lines of a Japanese gyokuro, while I’m happy with a more conservatively Chinese-styled infusion at around 3.5g. There are echoes of the nose’s oregano and olive oil with some artichoke, the signature nuttiness of Korean green tea, and even a hint of salty umami. Outstanding character and intensity with a mouth-cleaning mentholly character on end. While it’s easy to overbrew and can become fiercely bitter, when properly handled this tea has remarkable intensity coupled with great purity. Extraordinary stuff.

This tea is made with the leaf on the right…

This tea is made with the leaf on the right…

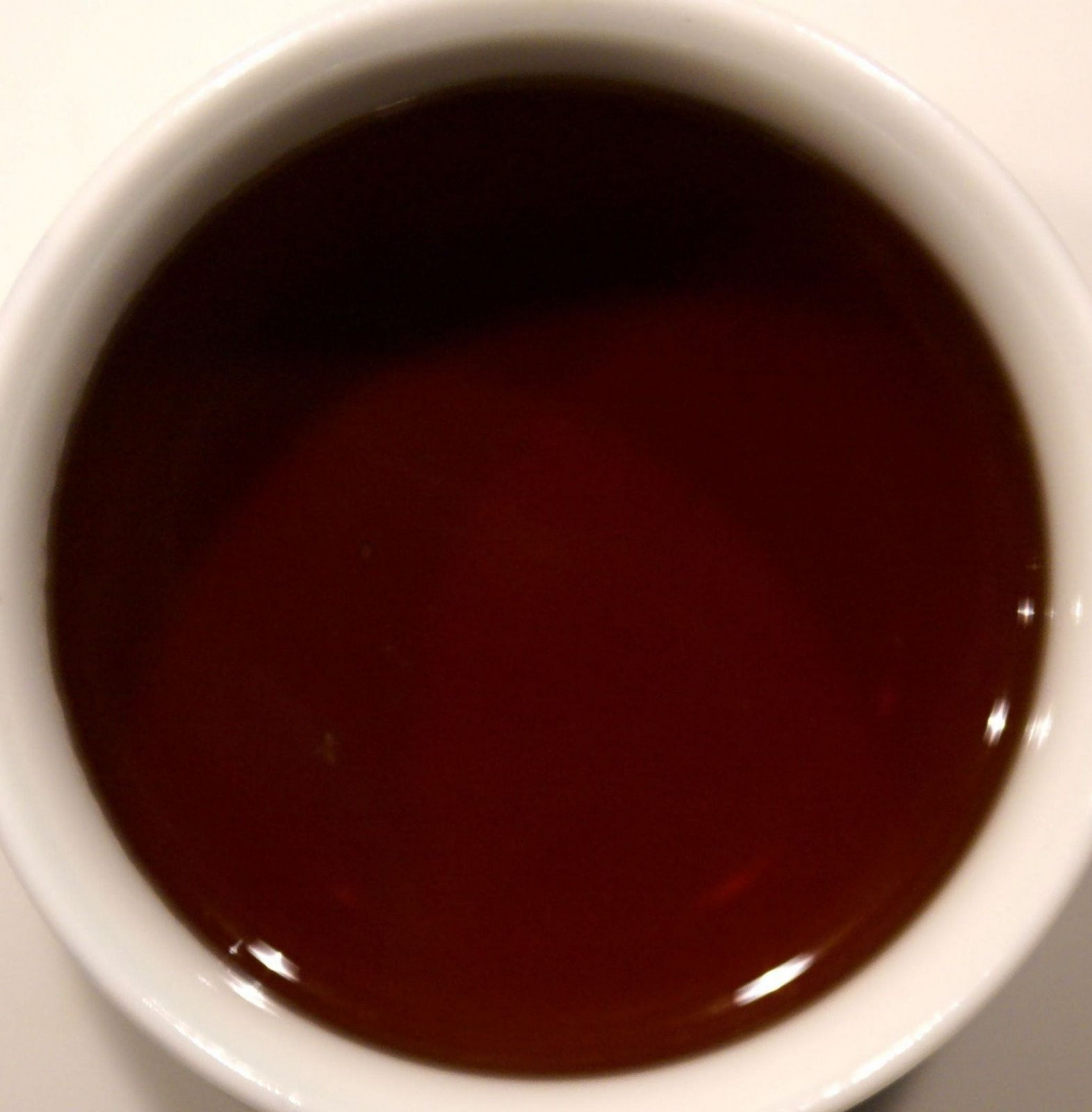

This is an extraordinary creature of a tea. Looking at the expired leaf (see photo above and below), there are still lots of intact whole leaves after 20 years! Really thick with very developed veins. This tea abounds in rough, elemental power, making it easy to believe the declared ‘wild tree’ provenance (how many modern puer can you say this about?). In purely drinking terms, it may lack the elegance (or ready-to-drinkness?) of the

This is an extraordinary creature of a tea. Looking at the expired leaf (see photo above and below), there are still lots of intact whole leaves after 20 years! Really thick with very developed veins. This tea abounds in rough, elemental power, making it easy to believe the declared ‘wild tree’ provenance (how many modern puer can you say this about?). In purely drinking terms, it may lack the elegance (or ready-to-drinkness?) of the