I owe gratitude for the present post to fellow internet tea lover

Fortunato, who kindly sent the following 13 samples of the œuvre of

Yoshiaki Hiruma, master teamaker from the region of Saitama (Japan’s northernmost tea growing district; read this good article

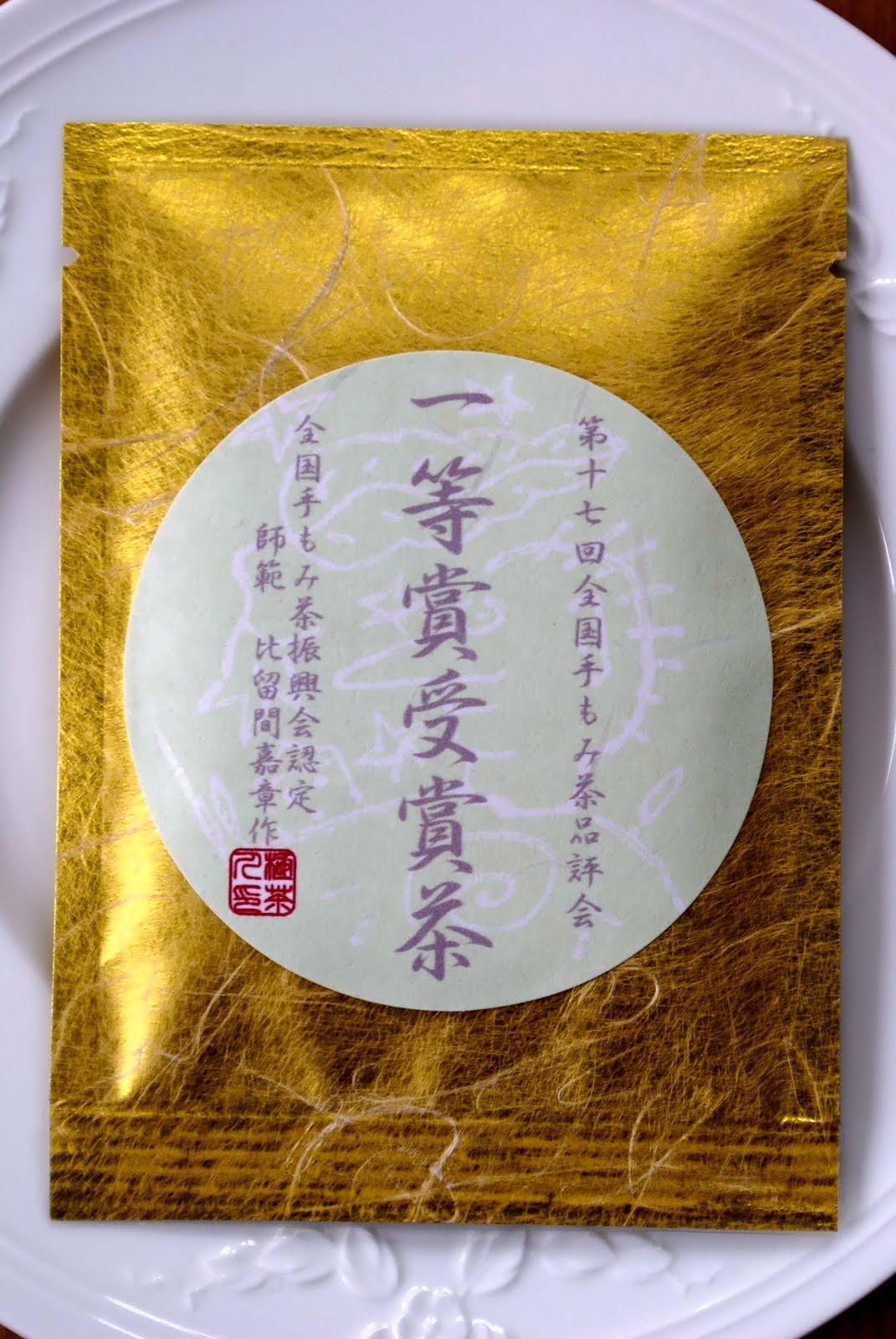

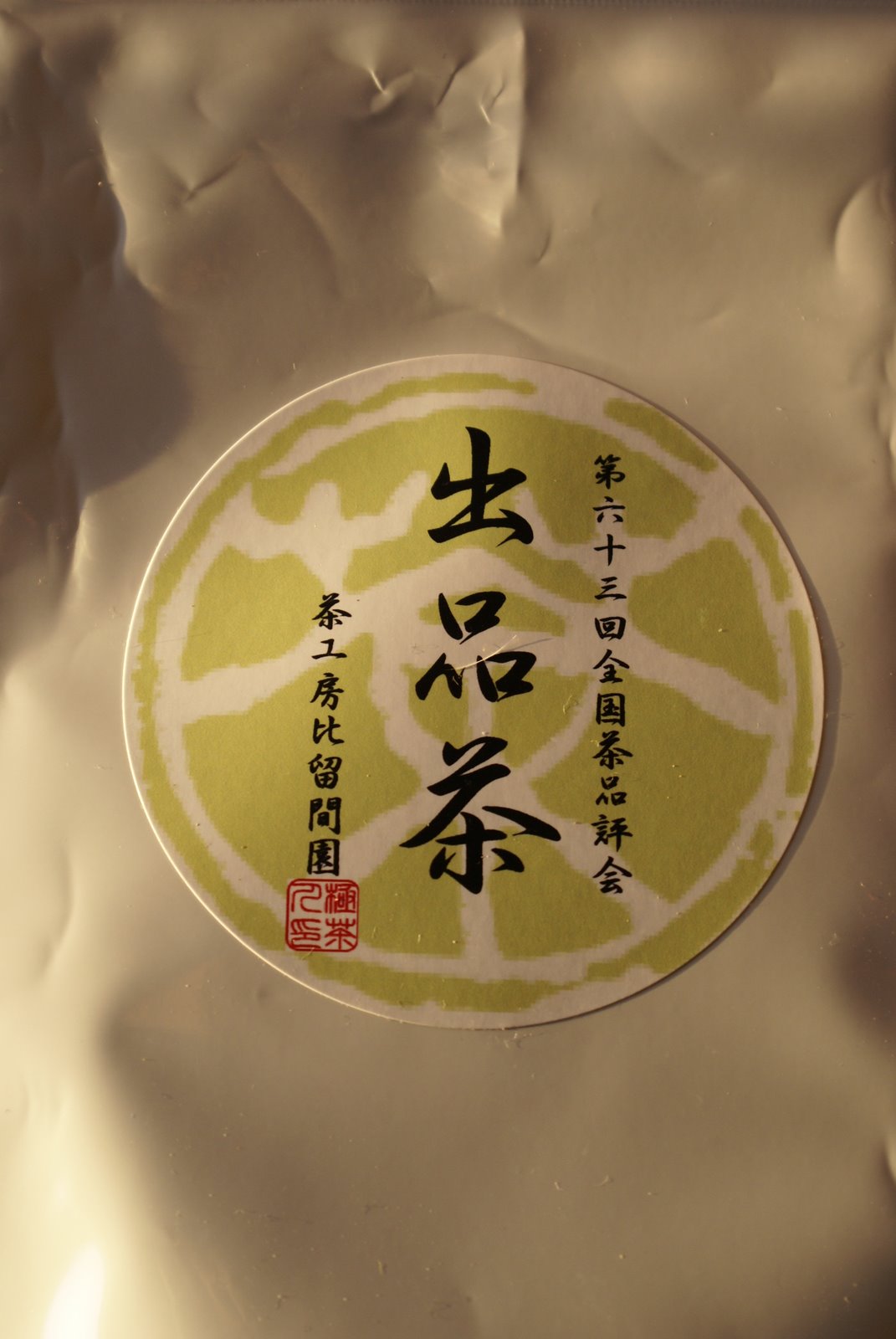

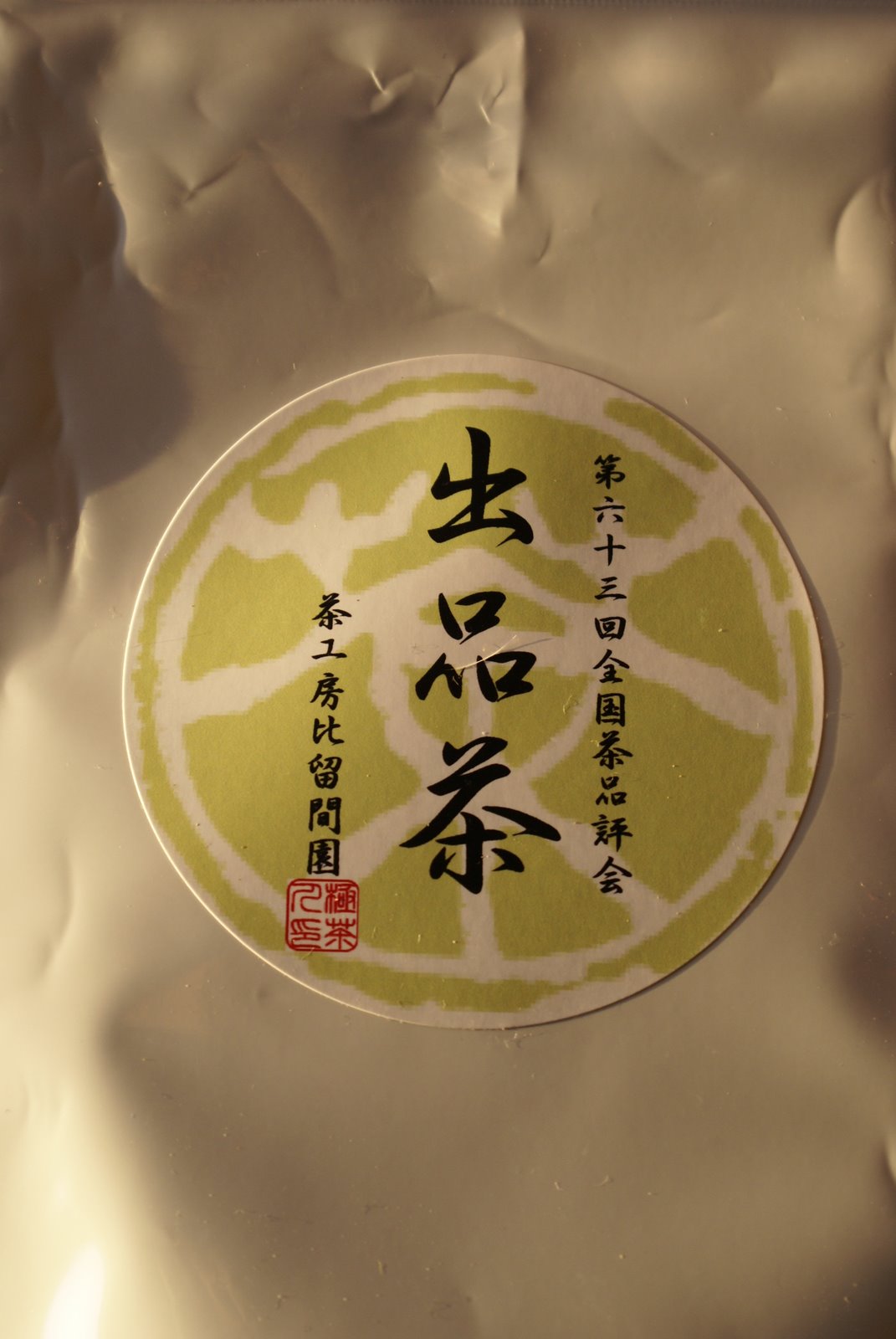

here). Mr Hiruma has achieved considerable success in recent years at the All-Japan competition, including with his

temomicha (see below) and

sencha, one of which won 3rd Prize in 2009, and also received the coveted 1st Prize from the Japanese Minister of Agriculture.

For those who read Japanese, Mr Hiruma has a website where his approach is explained. He is atypical in selling his own tea directly to consumers (Japanese tea is usually marketed by retailers, and is more often than not blended) and while mostly operating in Japan, he occasionally ships tea to the West with Paypal payment (contact him directly through the website for details). (See also this thread about Mr Hiruma on Teachat).

For all the teas below I have followed Mr Hiruma’s recommended brewing parameters. They are quite extreme, and crucially influencing the teas’ perception. While Japanese tea is usually brewed with medium-low dosage (2–3g of leaf per 100–150ml being the norm), Mr Hiruma advocates dosage as high as 5g / 50–60ml for some teas. That does make you raise an eyebrow. As an example, for the 3rd Prize Asamushi Sencha described below, it’s 5g / 60ml / 60C / 2 minutes. But actually only 34ml of liquid can be drained from the teapot (I’ve weighed this on an electronic scale), so it’s more of a ‘maceration’ than an actual brewing. It’s an approach that I’d call the gyokurization of sencha: a controversial policy, although it admittedly showcases the teas’ intensity and complexity on an unparalleled scale. Retrying some of the teas with more human parameters (usually 2.5g/100ml) yielded different results so please bear in mind that the below tasting notes are all taken with the Hiruma recommended parameters.

I started with two competition sencha teas. One Asamushi is a regional blend of Saitama and Mie leaves (Yabukita cultivar; two photos above), good-looking, sweet-vegetal, balanced, clean, voluminous with a fair bit of sweetness when brewed normally. With the recommended brewing parameters, the infusion is incredibly concentrated, magnifying the interplay between umami, sweetness, fatness and mild bitterness (the latter more pronounced as the tea cools down). The 3rd Prize Asamushi (also unblended Yabukita) is a more impressive grade, with immaculate short-steamed leaves that are extremely well-sorted. Little aroma in the cup with the recommended dosage of 5g/60ml, this is really outrageously concentrated with an explosion of flavour, dominated by sweetness over umami, later rounded off by some bitterish astringency; sweet over vegetal, long finish; there positively seems to be an added dimension of purity and intensity in this over the other competition asamushi.

One of the most memorable moments of these sessions was comparing four single-cultivar sencha teas alongside. Some of Mr Hiruma’s teas are blends of these (and several others), and it’s usual practice in Japan to operate a blend, unless your tea is from a wider-known variety such as the ubiquitous Yabukita, Yutakamidori (see a review here), Saemidori etc. Not only some of these Saitama-grown cultivars are fairly obscure (at least to me), but here is a rare opportunity to try them unblended. Put briefly, the differences in flavour and style are huge. The Fukumidori is processed as a rather highly fragmented fukamushi, with a strong spinach aroma and a Sauvignon-like profile of kiwi and lime; it gives a nicely tangy, zesty first brewing but fades quickly:

The Hokumei is sweeter, floral on nose and palate, almost milky in expression, with a very long finish; tasted blind I wouldn’t be sure this is sencha, it is so un-vegetal. The Sayamakaori is a chunky asamushi grade with kiwi tang and tannic potency in the flavour; more structured than charming, less sweet than the other varietals, this is a grown-up sencha that I’d qualify as austere. The most extraordinary, however, is the Yumewakaba: yielding a concentrated, creamy, almost almond milk-like brew with no astringency whatsoever, it is absolutely delightful.

Apart from standard sencha teas I’ve also tasted several oddities here, including a top-grade 2009 Kukicha Fukamushi Honeppoi Yatsu (pictured above and right) that combines the familiar high-roasted flavours of kukicha (stem tea) with echoes of umami green tastes so typical of fukamushi; and the 2009 Sencha Asamushi Chakakacha that has some flower buds added to the blend contributing to a very elegant, juicy, fruity, mildly floral tea.

Apart from standard sencha teas I’ve also tasted several oddities here, including a top-grade 2009 Kukicha Fukamushi Honeppoi Yatsu (pictured above and right) that combines the familiar high-roasted flavours of kukicha (stem tea) with echoes of umami green tastes so typical of fukamushi; and the 2009 Sencha Asamushi Chakakacha that has some flower buds added to the blend contributing to a very elegant, juicy, fruity, mildly floral tea.

One of the most peculiar creations of Hiruma is the bihakkou sencha, a tea that’s allowed to wither for a very short time before being processed like a sencha. The result is a very slightly oolonged green tea whose aromatic register shifts from the vegetal towards the floral. In fact the orchid and lilac notes come very close to a Taiwanese Baozhong, and there is no bitterness or dryness whatsoever in the flavour.

I tried four of these: the Seikakou (Sayamakaori cultivar; bottom photo above) starts very flowery and also emulates the buttery texture of Baozhong but is a bit simplistic and coarse (recommended brewing temp of 90C might have caused that); the Hanayaka (Hokumei cultivar; top above photo) is the most floral of the three, and very smooth on the palate with a low-key, elegant flavour; the Tsuyayaka (Yumewakaba cultivar) is less floral, chunkier in style, but has a very pleasant sweet baked bread expression, and a successful fukamushi-like cloudy second brew; the Kobashicha (Yumewakaba cultivar) sees a higher roasting. These are very distinctive teas for Japan, and inexpensive @ ¥2,500 / 100g. (All Hiruma teas are very well-priced, generally speaking). Mr Hiruma recommends a lower dosage here: 3g for 90ml (70C). I’m told he also makes a full-throttle oolong style called hanhakkucha – now that would really be interesting to try.

Mr Hiruma’s most extraordinary achievement, however, is temomicha – sencha that is entirely hand-processed and hand-rolled. Machine processing is what makes Japanese tea affordable, but leaf fragmentation inherent with this process adds coarseness and power at the expense of elegance. Hand processing – something that’s still the norm for some Chinese green teas and oolongs, but is extremely rarely seen in Japan – gives a pure expression of the tea leaves. Mr Hiruma obtained the 1st Prize at the All-Japan competition for his 2009 version (pictured above and below; it’s 100% select Yabukita trees). Composed of immaculate needle-shaped leaves, this tea has an exhilarating smell of sweet vegetality and tropical fruits, and brews one of the most distinctive infusions I’ve tasted in my short tea career (3g / 30ml / 55C / 2 minutes 30 seconds). At this extreme concentration the intensity is larger-than-life, though the colour remains a transparent pale white-emerald and the flavour is subtle, almost light on its feet. It is also extremely peculiar. Consisting almost exclusively of umami, it is most reminiscent of spinach and steamed salmon (I prefer not to write fishy, because it lacks the brothy boiled-fish aggressiveness of lower-grade sencha that this word is usually used to describe). Surprisingly, unlike Mr Hiruma’s senchas, this shows no overt sweetness; consequently the umami element is revealed in a purer, juicier, less ‘fat’ style than usually. It’s a little like eating a good home-made Chinese meal prepared with fresh veggies and unsalted water after a lengthy diet of MSG-enhanced food.

In summary, these are some of the most extraordinary teas I’ve tasted. Totally handcrafted with fantastic personality. May the good word of Mr Hiruma spread around the tea world.