Other posts in this series:

2008 Gyokuro Kame-Jiru-Shi (O-Cha)

2008 Gyokuro Tama Homare (Marukyu)

2008 Kabusecha Takamado (Marukyu)

2008 Sencha Miyabi (O-Cha)

2009 Shincha Fukamushi Supreme (O-Cha)

2009 Shincha Shigaraki (Marukyu)

2009 Shincha Shuei (Marukyu)

2009 Shincha Uji Gold (Marukyu)

2009 Shincha Yutakamidori (O-Cha)

There are many aspects of the Japanese civilisation that I find totally incomprehensible (such as pachinko) and many others that I find highly admirable.

One such aspect is the pragmatic savviness that is applied to tea production. Unlike those crazy Chinese that insist on making tea from whole leaves and often conduct only one harvest per year, the Japanese really make their tea trees and leaves work hard for their living. From the most immaculate gyokuro to the lowliest genmaicha nothing is ever wasted and everything is produced with logic and order.

Your summer harvest has produced large leaves with no finesse and lots of bitterness? Roast them and sell cheaply to restaurants as bancha. Lots of substandard leaves in your sencha? Mix with puffed rice and a bit of tea powder for a good genmaicha. Gyokuro yields low and takes a long time to cash in? There’s always market for an earlier release of affordable kabusecha.

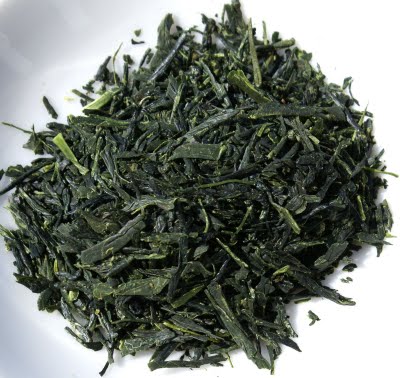

The Japanese tea tradition has also created a number of products made from material that elsewhere would be considered leftovers. Tea debris from the production of sencha or other grades make mecha and konacha. And then there are stems, stalks and twigs. Surely there’s the occasional twig in some oolongs (like the Young Tree Baozhong from Tea Masters), and most puer is made with leaves attached to the stems, but the latter’s amount remains marginal. Kukicha, on the other hand, is a Japanese speciality made mostly from stems with some addition of leaf; the whole is roasted and yields a rich, toasty, grainy infusion that is low in caffeine and reputed to be even healthier than ‘standard’ green tea. Here’s an image of a standard kukicha:

.jpg)

When the stems are a by-product of a higher grade material, the obtained tea is renamed karigane. Karigane is rarely roasted, so that you can taste the flavour of quality stems in its unadulterated sweetness and creaminess. Usually it is blended with a proportion of leaf for a richer taste.

The 2008 Otowa Gyokuro-Karigane I am tasting today is yet another tea from the ever-so-reliable Marukyu-Koyamaen. It is the aristocracy of stem tea: tiny young tea shoots blended with gyokuro-grade leaf. The visual aspect is quite delightful and so is the aroma: spinach-vegetal but with a rounder, richer, almost white-chocolatey dimension than a leaf-only tea.

.JPG)

3g of Karigane separated into 0.9g of stems (left) and 2.1 of gyokuro-grade leaf (right).

Eager to find out more, I sacrificed an hour to separate the stems from the leaves in a 3g sample. It turns out that the former constitute less than half the material here (1/3 by weight, but they’re lighter than the leaves proper). Then I brewed these two fractions separately. The leaves are of excellent quality yielding a sweet, excitingly raspberry-scented, gyokuro-styled infusion. Really surprising. As for the stems, I expected the brew to be quite thin but in fact it is quite intense. Karigane is often described as ‘sweet’ and ‘creamy’ but these stems are giving a bone-dry, rather woodsy, dried-herby flavour. Interesting.

Infused karigane stems (top), karigane leaves (bottom left) and kukicha (bottom right).

It was not the end of my exploration. While centuries of practice and gazillions of reference points have contributed to setting the best infusion parameters for classic tea such as sencha and gyokuro, karigane is trickier. Should you brew it like the leaf it is based on? Or with hot water and longer times to extract the maximum from these tiny stems? I explored all the alternatives in a series of comparative tastings, and came up with the following table:

|

50C

|

60C

|

70C

|

|

1 gram

|

Light colour. Decent umami personality here but unintense. Not bad if you like your Japanese tea quite light. Only one good brewing.

|

|

Moderate intensity even at this highish temperature. Unremarkable, plus the stale, seaweedy element dominates.

|

|

2 grams

|

Brews very light but the glutamic thickness is obvious. Really interesting how this develops more texture and sweetness than at higher temperatures. Lacks a bit of oomph if you like an ‘expressive’ tea, otherwise I found it as good as a higher dosage at this temperature.

|

More aroma and intensity to the flavour than the 50C version but somehow loses thickness (because it isn’t extracted, or its perception is masked by the higher temperature of tea in cup?). A clear taste of umami and all in all a good compromise. I also like the 2nd brewing here.

|

Very similar to the 60C version, again seems less thick than the 50C. Quite vegetal. 2nd brewing is OK. But no doubt this temperature is too high to obtain good extraction and balance.

|

|

3 grams

|

Good thickness but profile is less transparent than with 2 grams: umami clashes with spinach vegetality. A touch bitter. But also good sweetness. This dosage is OK if you want a proper session of 3–4 infusions.

|

|

A deeper colour. At 70C this is quite more nutty than the 2-gram version. Less finesse and less interest. More vegetality than umami. Some interest to the second brew.

|

One of my comparative tastings: 1, 2 and 3 grams of leaf (from left to right).

Having found out the best dosage (2g) and brewing temperature (60C) I went on to compare various brewing times:

|

1 minute

|

2 minutes

|

3 minutes

|

|

Colour is pale but a nice brewing, good mixture of sweetness and umami, not too intense or long but there’s a glutinous kiss on the finish. Representative and there’s no need for a longer steeping.

|

Little change to the 1-minute version apart from the colour and the stem influence: a more woodsy, herby taste. Sweetness is masked though, the whole is chunky and slightly lacks charm.

|

Almost identical to the 2-minute version, as if the extraction stopped. Not very sweet and no more interest than the 1-minute.

|

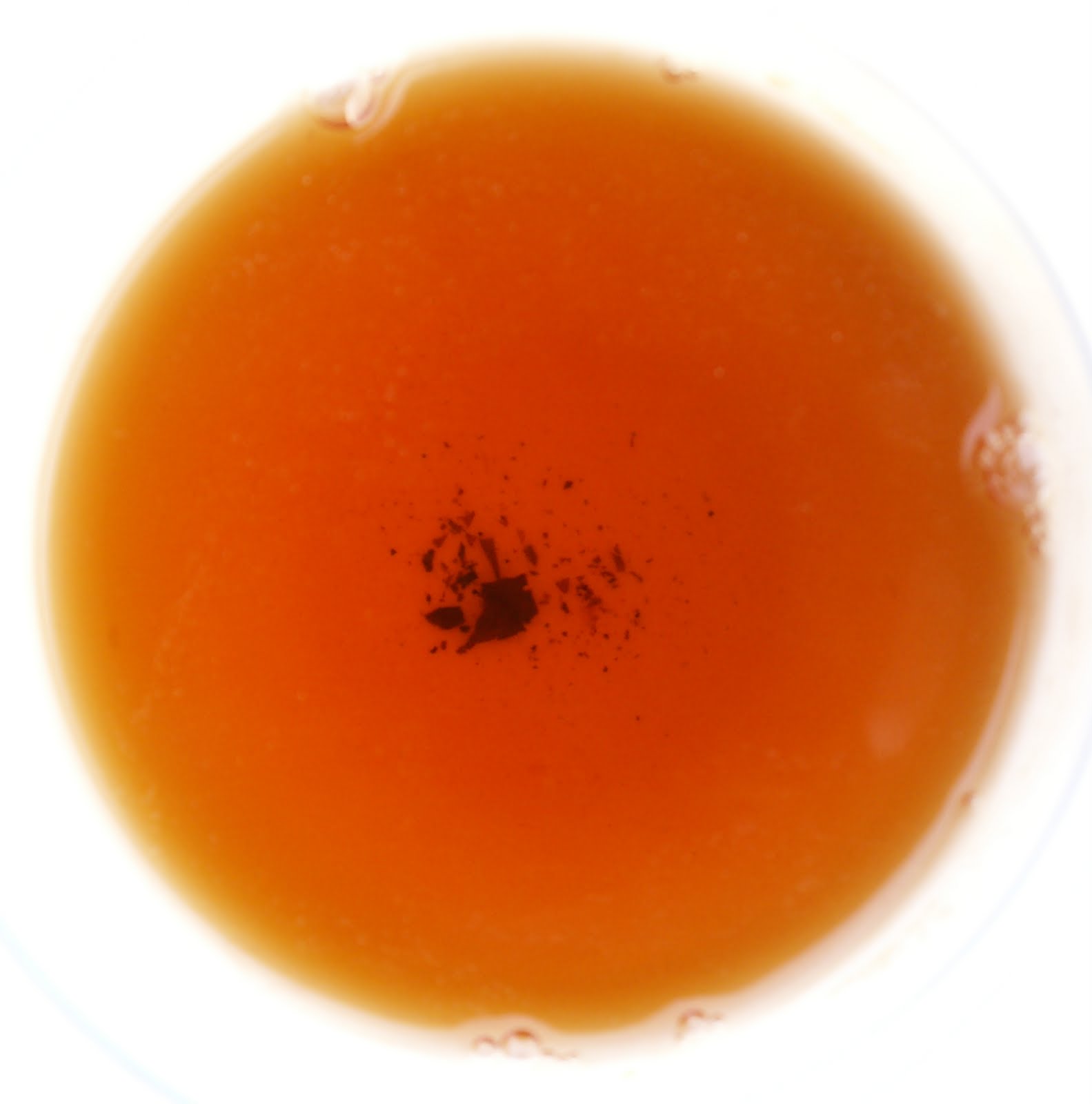

Colour of first infusion with ‘standard’ parameters (3g / 100ml / 60C / 60 seconds).

To summarise, this aristocratic karigane should be brewed like a gyokuro, with warm not hot water (55–60C seems best). 2 grams of leaf per 100ml of water is a good dosage; infusion times can vary but short ones (60 seconds) are pretty good.

This is a truly interesting tea: I can’t remember spending so much time recently with a single tea, and I hardly got bored. It shows a bit of 2008 staleness to it (I identify it as dried herbs and seaweeds) but it’s not too obtrusive. The key is to brew it properly. Done sencha-style it is underwhelming with little personality, but gyokuro-style is a completely different animal. Little aroma but on the palate this erupts with glutamic density and length, with good sweetness and an added herby dimension from the leaf. A challenging taste if you’re not ‘of the school’ but impressive for sure. And at ¥1575 / 90g can it is really good value.

.jpg)