In my book, the only real usefulness of blind tasting is to develop your own palate and tasting mind by making educated guesses. Tasting a single wine blind, you are forced to concentrate really hard on all its aspects: you have no reference points to assist you in your interpretation.

My palate for tea is that of a beginner, and I find blind tasting a truly useful exercise. It was an exciting perspective, therefore, to receive two unlabelled tea samples from fellow US tea drinker, Kimble22 (a.k.a. Shibumi – check out his blog here). I tasted them as analytically as possible (these were no pleasure sessions) and come up with approximate conclusions. Perhaps, looking at the photos and reading my descriptions, you’ll have better ideas: let me know as I’ll hold on posting the teas’ real identity (which I still don’t know) for a few more days.

An exercise matching tea and chocolate. Can this work at all? Isn’t chocolate too powerful to have with tea? I try some artisanal chocolate pralines with green, oolong, black and puer tea.

How to brew decent tea while travelling? Without access to infinite tea supply from your own tea cabinet and 25 brewing utensils. The answers are: keep it simple; carry your own tea; choose a tea that will perform well in less-than-perfect circumstances.

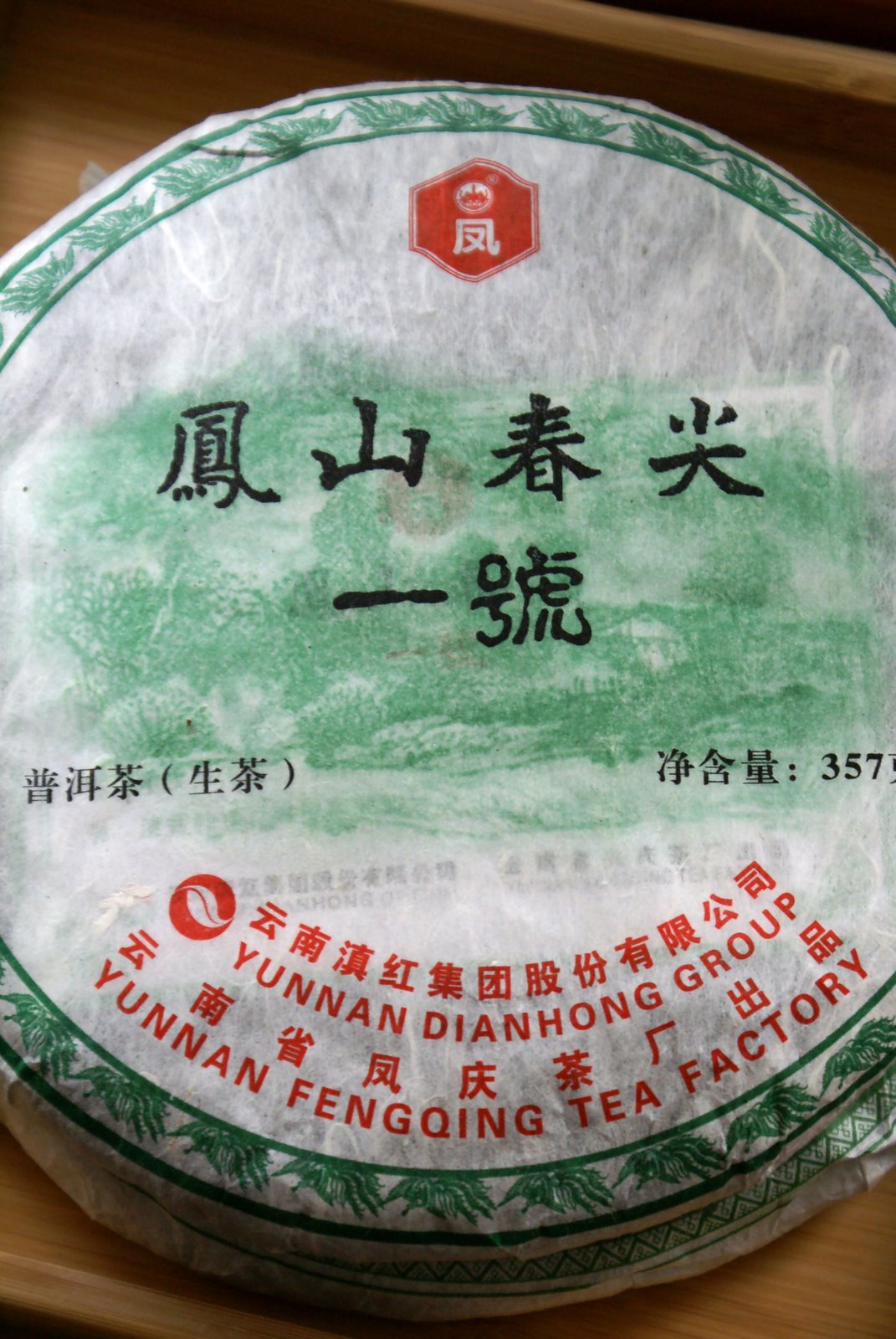

It might have done so for some upper-bracket brands but the large tea factory of Fengqing (a.k.a. Dianhong Group, hinting at their main activity as a black tea producer) has remained more than reasonable in its pricing. If you browse the internet for opinions about their puer teas, it’s usually dismissive: they’re cheap, basic and uninspiring. Perhaps I’ve been in a forgiving mood of late but I found this utterly satisfying for the price (and better than many $15–20 cakes). One thing it needs is a generous dosage. In fact my initial attempts at 2–3 grams or competition style produced an unaromatic, content-less and anonymous tea. Much better with double that amount of leaf.

Brewed in: dahongpao pot

Dosage: 6g / 130ml

Dry leaf: Compression is rather loose, and the leaves are very easily separated into a clean and intact collection. Reasonable leaf size, minor amount of tips – nothing special here but the quality is good. Wet leaf is quit thin and clearly plantation-grown but mostly wholish and intact, adding to the good overall impression.

Brewing #1 (30 seconds in clay pot)

Tasting notes:

20s: Fairly enjoyable: it is obviously a rather generic pu but at this dosage nicely intense, with medium pale (but not the palest yellow) colour and sweet tobacco dominating in the aroma cup.

30s: As tasty as brewing #1 but a bit less alive, slowly receding into a generic bean-like chewiness and sweetness. Quite some bitterness appearing, but it is of the clean, energetic, positive kind.

40s: More beany character but there are also hints of apricot and almost flowers replacing tobacco in the aroma cup. Some citrusy bitterness on end. Not massively structured but better than expected for the price. Dosage is the key to satisfaction here.

40s, 70s, 60s. Slowly becoming a little generic-candy but still satisfyingly intense. Brewings #5–6 still very good indeed: good huigan.

3m: Surely quite light in flavour but there is still enough bean, mushroom and sweet candy for interest. Long live high dosage. This delivers another half-dozen of gradually fading infusions (provided you keep the times short).

Overall this has all the characteristics of a basic but well-made sheng: tobacco, old wood, beans, some citrus, some invigorating bitterness, reasonable patience. It takes a lot of leaf in the pot to show content and texture, but at this price I don’t mind it at all. This tea will not sparkle a romance with puer if you’re still to be converted, but is really a smart choice if you need (who doesn’t?) an inexpensive tea for various mundane uses. I’m happy I bought it.

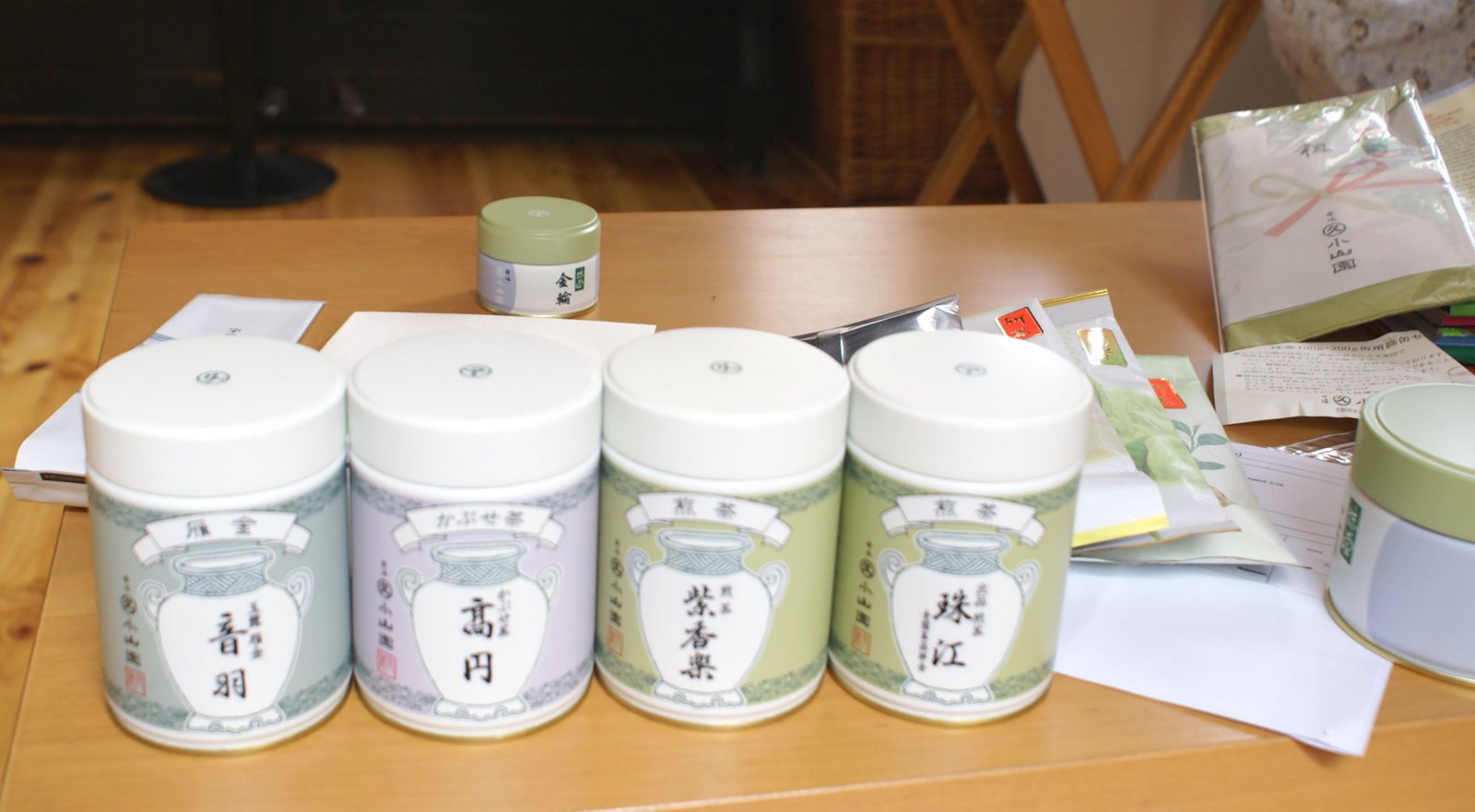

By pure coincidence (well, a polite way to thank Polish Mail for holding packages for two weeks for ‘customs inspection’) I’ve received no less than four shipments of tea today. Now this is real embarras de richesse! My Japanese 2009s are here (tins on the photo above are from Marukyu-Koyamaen and there’s another box from O-Cha; I must praise the latter’s service as they’ve replaced an order that went missing, free of charge on EMS) and I’ll dedicate a series of future posts of various shinchas and gyokuros from these two vendors.

By pure coincidence (well, a polite way to thank Polish Mail for holding packages for two weeks for ‘customs inspection’) I’ve received no less than four shipments of tea today. Now this is real embarras de richesse! My Japanese 2009s are here (tins on the photo above are from Marukyu-Koyamaen and there’s another box from O-Cha; I must praise the latter’s service as they’ve replaced an order that went missing, free of charge on EMS) and I’ll dedicate a series of future posts of various shinchas and gyokuros from these two vendors.

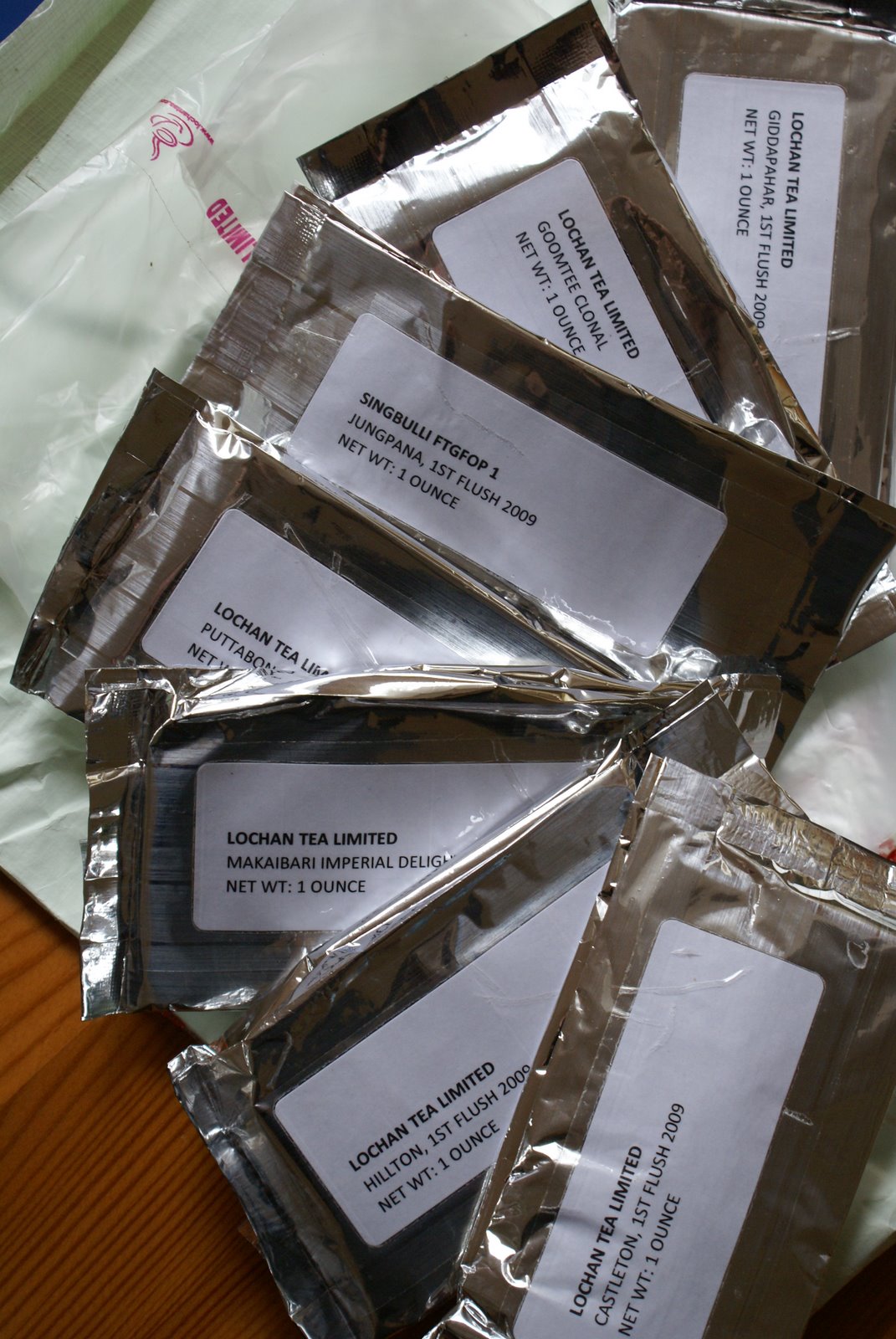

By contrast I’ve also ordered a box of various aged puer samples from Nadacha (and some excitingly affordably yixing clay jars):

I’ve started the exploration with a black tea from Nada:

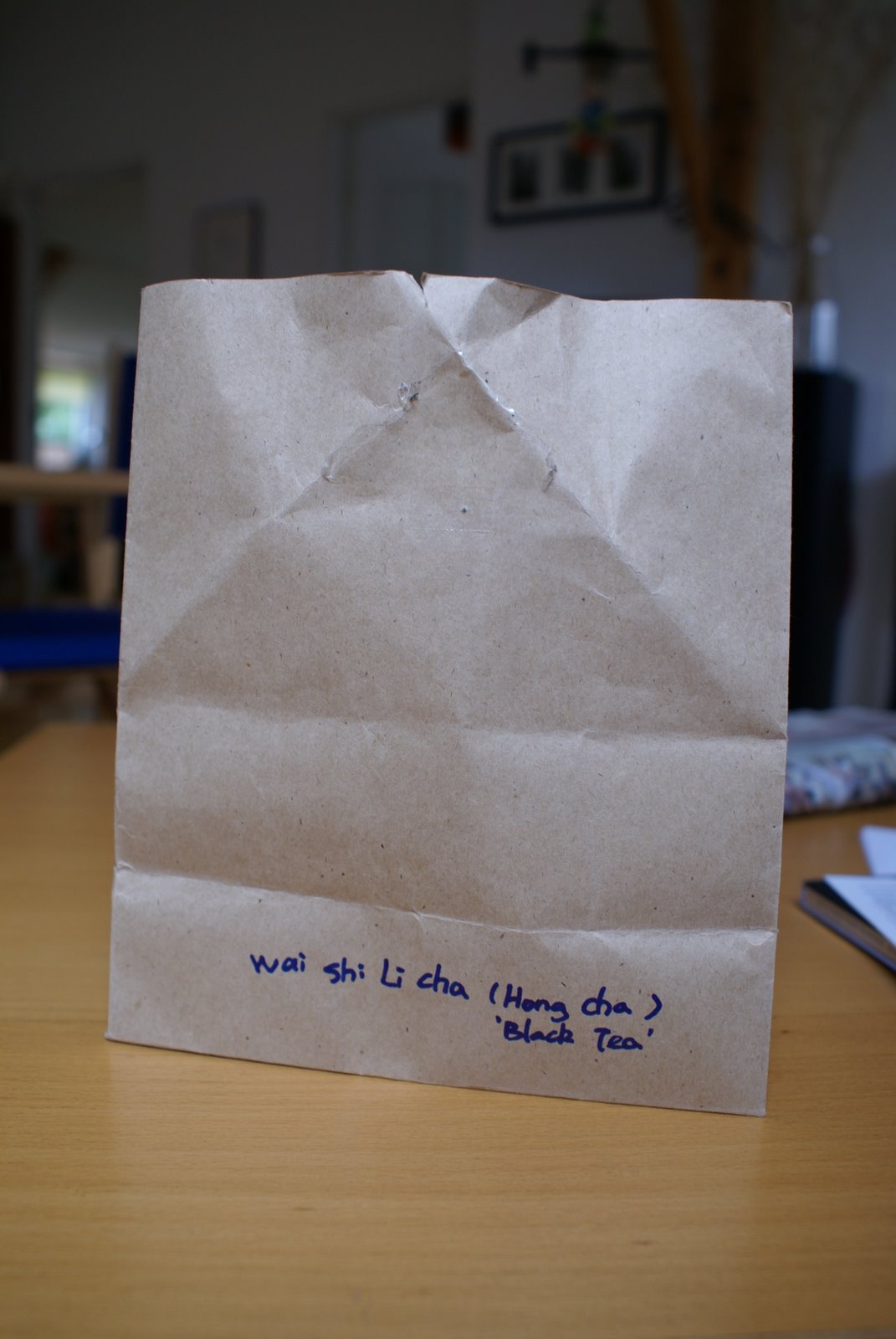

The 2009 Fengqing Wai Shi Li is a high-grade spring flush from the Fengqing Tea Factory (and more specifically their Dianhong brand) who are classic producer of both black tea and (more recently) puer. It’s fairly inexpensive at £6 / 100g, and I also very much like Nada’s wabi-sabi packaging:

Brewed in: gaiwan

Dosage: 3g/140ml

Dry leaf: Rather small leaves with a degree of golden tips but overall colour is darkish. Aroma is typically Yunnan and very hongcha: earthy, herby, rather unfruity, not terribly complex or deep; perhaps a bit of smokiness. No increase in intensity as the leaf is warmed.

Tasting notes:

45s: The profile of this brew is best described as ‘traditional’. It has a subdued aroma dominated by earth and smoke, with no fruit frills. The nose might be unremarkable but the flavoury is very good, with medium body and a less oblivious oxidation than I expected from the nose. Hardly a lot of complexity or poise but this is good for the price. I might have been just lucky with the brewing parameters as this is showing a perfect balance of tannins and body. Really quite traditional: rather solid and oxidised, less fruity than many modern examples of black Yunnan but more consistent and solid.

Overall this is satisfying tea for the price. Another good buy from Nada! This also makes me curious about the

other 2009 Fengqing black that he’s offering.

Value for money

This tea is one of the main productions from one of the main tea factories, and has been widely discussed on the internet (see e.g. here). I would perhaps have liked more content and density but for what is essentially a village-level tea at an affordable price, this is really well-composed with some depth and some grip to this safe, commercial, unintense style.

Mengku Old Tree 2008

Merchant: Dragon Tea House

Price: $12 / 400g cake

Brewed: competition style + subsidiary notes in dahongpao pot (5g / 120ml)

Yesterday night, in memory of those who perished on the Square of Heavenly Peace two decades ago, I brewed a very special Chinese tea in a commemorative tea ceremony. A full-blown chaxi (tea setup), such as I never prepare. I slowly brought the best Polish mineral water to a boil in my earthenware kettle, put dry leaves of the 1989 Jiang Cheng Wild Tree Brick in my dahongpao yixing clay pot, and let it infuse slowly. The tea was brewed in silence and no tasting notes were taken.

This outstanding tea, produced a few weeks before the mournful event, is full of unabated elemental force and seemed a more than appropriate homage to the departed. What follows is an account of an earlier tasting session with photographs from today, as I finished off the leaves from yesterday’s session.

This is an extraordinary creature of a tea. Looking at the expired leaf (see photo above and below), there are still lots of intact whole leaves after 20 years! Really thick with very developed veins. This tea abounds in rough, elemental power, making it easy to believe the declared ‘wild tree’ provenance (how many modern puer can you say this about?). In purely drinking terms, it may lack the elegance (or ready-to-drinkness?) of the 1999 Menghai #7532 but shows an unadulterated old style of sheng puer when no concessions were made for the modern yuppie public and teas were made to last decades. I wouldn’t have liked to be near these leaves in 1989. A majestic tea of authority and austerity. And right for the occasion, I would say.

This is an extraordinary creature of a tea. Looking at the expired leaf (see photo above and below), there are still lots of intact whole leaves after 20 years! Really thick with very developed veins. This tea abounds in rough, elemental power, making it easy to believe the declared ‘wild tree’ provenance (how many modern puer can you say this about?). In purely drinking terms, it may lack the elegance (or ready-to-drinkness?) of the 1999 Menghai #7532 but shows an unadulterated old style of sheng puer when no concessions were made for the modern yuppie public and teas were made to last decades. I wouldn’t have liked to be near these leaves in 1989. A majestic tea of authority and austerity. And right for the occasion, I would say. The Chablis of tea: a worthy name for one of China’s greatest greens.