Georgia in the Caucasus. ‘The cradle of wine’, as it styles itself without false modesty. While I think recent research gives priority to China, Georgia is indeed where the wine we drink today – European, Mediterranean wine – originated some 5,000 years ago. And surprisingly much of this heritage directly influences modern Georgian wines. Including Georgia’s greatest assets, its 500+ indigenous grape varieties. Some are the result of 2, 3, 4,000 years of genetic selection. Once the country modernises its wine industry and small family-owned domaines get to do some serious quality work in the vineyards, I’m sure you’ll hear about Saperavi, Rkatsiteli and Mtsvane.

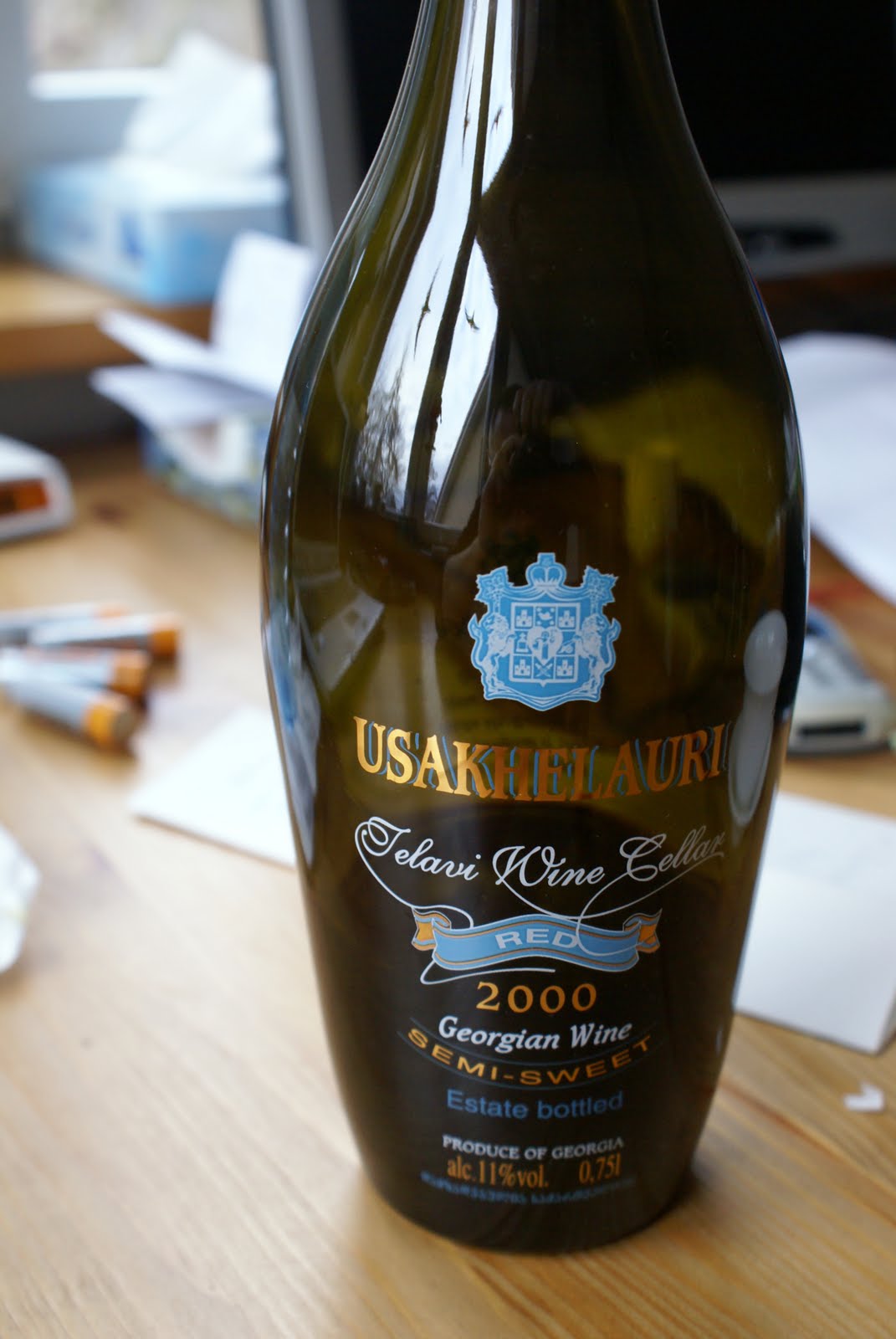

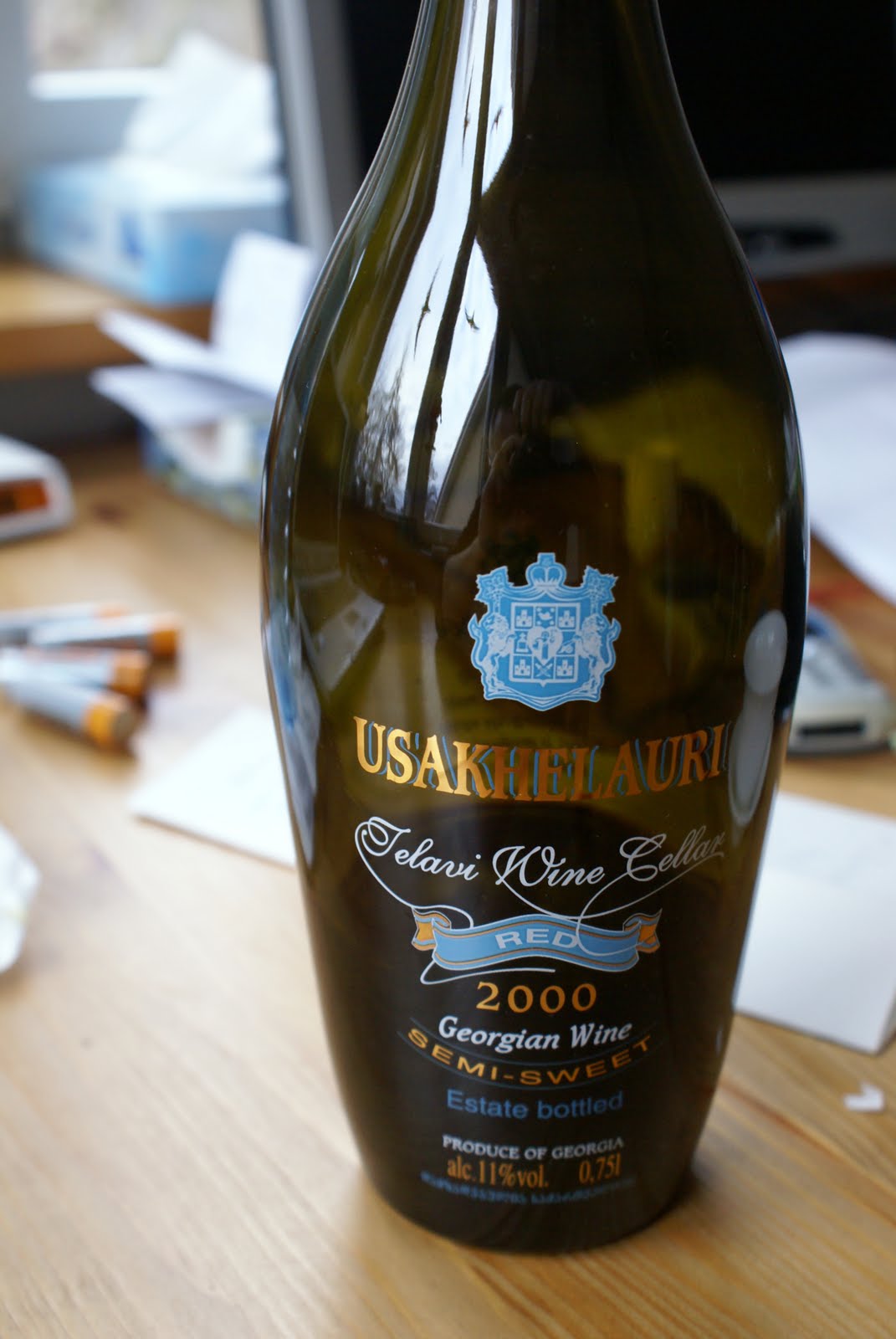

Some of these grapes are widespread and grow on hundreds or thousands of hectares while other are very obscure and limited to single villages. Usakhelauri is one of them. While very famous in the past for its exquisitely flowery, velvety sweet wines, it is difficult to grow and has fallen out of favour. It’s hard to get trustworthy information but apparently it is now grown on around 1 ha of vines in the central Georgian region of Racha. Only two companies use it: Teliani Valley and Telavi Wine Cellar. The latter’s production is only 700 bottles a year. I was fortunate enough to receive a bottle of this expensive wine (retailing for around $40) upon my last visit to Georgia in 2005.

One of Georgia’s oddities is its wide range of ‘semi-sweet’ red wines. Produced by artificially stopping the fermentation when the wines reach c. 11% alc. and 50g residual sugar, they are surely an acquired taste, and are frequently frowned upon. I remember some vitriolic comments from Western critics after their trips to Georgia. Out of context, these wines cans surely seem odd (and many are pretty awful). In Georgia they are served in the afternoon over teatime nibbles that include dried and fresh fruits, nuts, fruit preserves, as well as tea and coffee. It’s difficult to find a wine that would pair well with such foods and drinks without being too alcoholic (as port and sherry are). Sweetish Georgian reds fill this gap. And when well-made from quality grapes, they can really be delicious.

This Telavi Wine Cellar Usakhelauri 2000 is a very good surprise. It’s only faintly sweet, balanced by really high acidity (I’d categorise this as semi-dry really). It tastes very young, with no evolution at all, and has a very good expression of crisp red cherry and damson fruit, with perhaps a bit of Usakhelauri’s notorious floral bouquet. Not too tannic but with plenty of vinosity: while many Georgian sweet reds can taste like a diluted home-made currant wine, this is the real thing. I’ve learned to appreciate its usefulness at the coffee table and a perfect match with festive conversation when we’ve had guests at 4pm yesterday. Port would have been too heavy, sweet Riesling too light, Tokaj too sharp, oaky Sauternes completely out of place. This Usakhelauri called for attention (for a moment) and kept the company spritely and good-humoured. The Georgians know how important that is: they spend a lot of time at family and friendly gatherings, talking a lot and drinking a lot. Thank God for the Georgians.

Everything you’ll need to match with Usakhelauri.

Disclaimer

Source of wine: gift from the winery upon a visit in 2005.