(9) 2008 Kame-Jiru-Shi Gyokuro

Gyokuro: any other tea that triggers the same sense of excitement and festivity?

Gyokuro: any other tea that triggers the same sense of excitement and festivity?

Other posts in this series:

2008 Gyokuro Kame-Jiru-Shi (O-Cha)

2008 Gyokuro Tama Homare (Marukyu)

2008 Kabusecha Takamado (Marukyu)

2008 Sencha Miyabi (O-Cha)

2009 Shincha Fukamushi Supreme (O-Cha)

2009 Shincha Shigaraki (Marukyu)

2009 Shincha Shuei (Marukyu)

2009 Shincha Uji Gold (Marukyu)

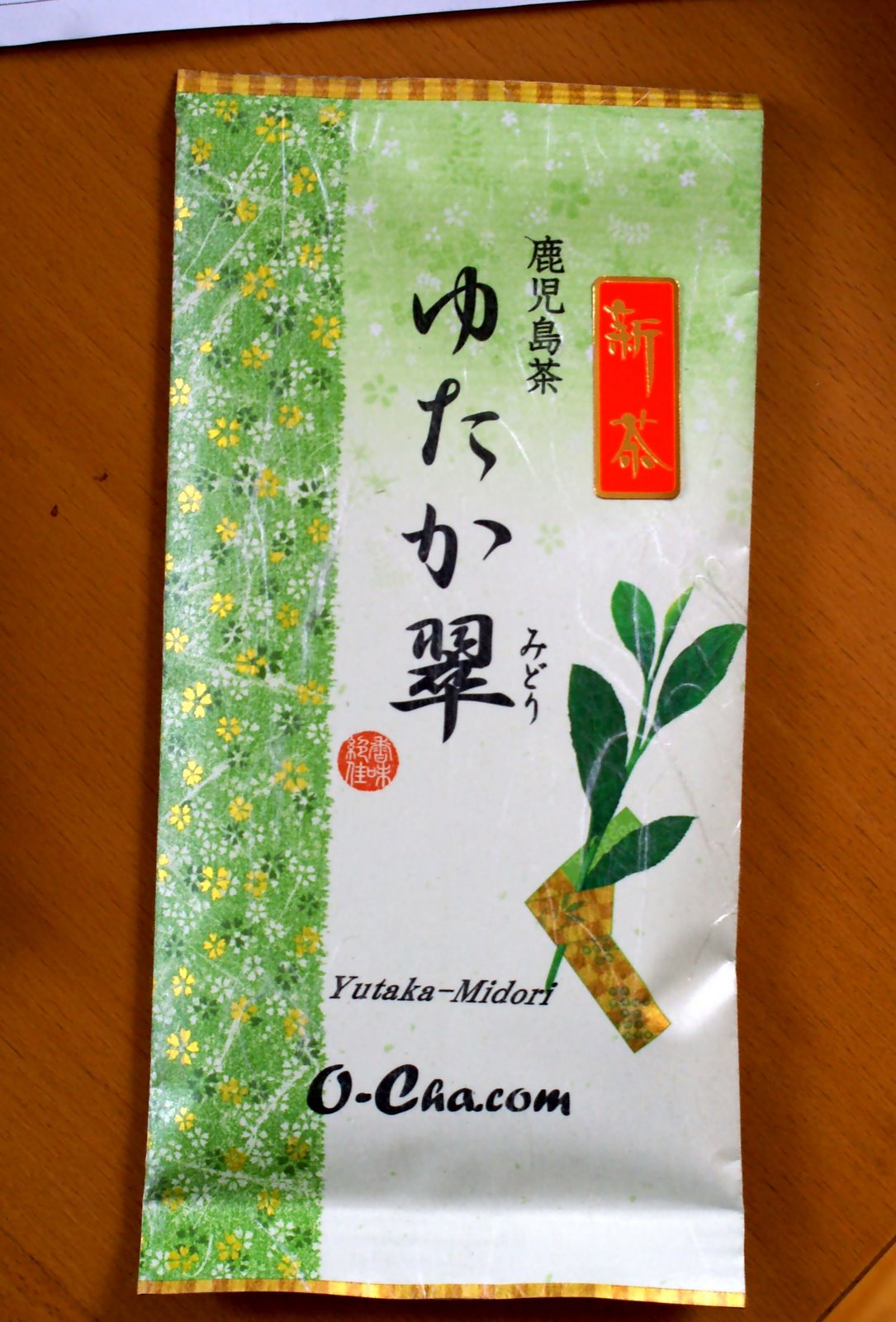

2009 Shincha Yutakamidori (O-Cha)

There are many aspects of the Japanese civilisation that I find totally incomprehensible (such as pachinko) and many others that I find highly admirable.

One such aspect is the pragmatic savviness that is applied to tea production. Unlike those crazy Chinese that insist on making tea from whole leaves and often conduct only one harvest per year, the Japanese really make their tea trees and leaves work hard for their living. From the most immaculate gyokuro to the lowliest genmaicha nothing is ever wasted and everything is produced with logic and order.

Your summer harvest has produced large leaves with no finesse and lots of bitterness? Roast them and sell cheaply to restaurants as bancha. Lots of substandard leaves in your sencha? Mix with puffed rice and a bit of tea powder for a good genmaicha. Gyokuro yields low and takes a long time to cash in? There’s always market for an earlier release of affordable kabusecha.

The Japanese tea tradition has also created a number of products made from material that elsewhere would be considered leftovers. Tea debris from the production of sencha or other grades make mecha and konacha. And then there are stems, stalks and twigs. Surely there’s the occasional twig in some oolongs (like the Young Tree Baozhong from Tea Masters), and most puer is made with leaves attached to the stems, but the latter’s amount remains marginal. Kukicha, on the other hand, is a Japanese speciality made mostly from stems with some addition of leaf; the whole is roasted and yields a rich, toasty, grainy infusion that is low in caffeine and reputed to be even healthier than ‘standard’ green tea. Here’s an image of a standard kukicha:

.jpg)

When the stems are a by-product of a higher grade material, the obtained tea is renamed karigane. Karigane is rarely roasted, so that you can taste the flavour of quality stems in its unadulterated sweetness and creaminess. Usually it is blended with a proportion of leaf for a richer taste.

The 2008 Otowa Gyokuro-Karigane I am tasting today is yet another tea from the ever-so-reliable Marukyu-Koyamaen. It is the aristocracy of stem tea: tiny young tea shoots blended with gyokuro-grade leaf. The visual aspect is quite delightful and so is the aroma: spinach-vegetal but with a rounder, richer, almost white-chocolatey dimension than a leaf-only tea.

3g of Karigane separated into 0.9g of stems (left) and 2.1 of gyokuro-grade leaf (right).

Eager to find out more, I sacrificed an hour to separate the stems from the leaves in a 3g sample. It turns out that the former constitute less than half the material here (1/3 by weight, but they’re lighter than the leaves proper). Then I brewed these two fractions separately. The leaves are of excellent quality yielding a sweet, excitingly raspberry-scented, gyokuro-styled infusion. Really surprising. As for the stems, I expected the brew to be quite thin but in fact it is quite intense. Karigane is often described as ‘sweet’ and ‘creamy’ but these stems are giving a bone-dry, rather woodsy, dried-herby flavour. Interesting.

Infused karigane stems (top), karigane leaves (bottom left) and kukicha (bottom right).

It was not the end of my exploration. While centuries of practice and gazillions of reference points have contributed to setting the best infusion parameters for classic tea such as sencha and gyokuro, karigane is trickier. Should you brew it like the leaf it is based on? Or with hot water and longer times to extract the maximum from these tiny stems? I explored all the alternatives in a series of comparative tastings, and came up with the following table:

|

50C |

60C |

70C |

|

|

1 gram |

Light colour. Decent umami personality here but unintense. Not bad if you like your Japanese tea quite light. Only one good brewing. |

Moderate intensity even at this highish temperature. Unremarkable, plus the stale, seaweedy element dominates. |

|

|

2 grams |

Brews very light but the glutamic thickness is obvious. Really interesting how this develops more texture and sweetness than at higher temperatures. Lacks a bit of oomph if you like an ‘expressive’ tea, otherwise I found it as good as a higher dosage at this temperature. |

More aroma and intensity to the flavour than the 50C version but somehow loses thickness (because it isn’t extracted, or its perception is masked by the higher temperature of tea in cup?). A clear taste of umami and all in all a good compromise. I also like the 2nd brewing here. |

Very similar to the 60C version, again seems less thick than the 50C. Quite vegetal. 2nd brewing is OK. But no doubt this temperature is too high to obtain good extraction and balance. |

|

3 grams |

Good thickness but profile is less transparent than with 2 grams: umami clashes with spinach vegetality. A touch bitter. But also good sweetness. This dosage is OK if you want a proper session of 3–4 infusions. |

A deeper colour. At 70C this is quite more nutty than the 2-gram version. Less finesse and less interest. More vegetality than umami. Some interest to the second brew. |

One of my comparative tastings: 1, 2 and 3 grams of leaf (from left to right).

Having found out the best dosage (2g) and brewing temperature (60C) I went on to compare various brewing times:

|

1 minute |

2 minutes |

3 minutes |

|

Colour is pale but a nice brewing, good mixture of sweetness and umami, not too intense or long but there’s a glutinous kiss on the finish. Representative and there’s no need for a longer steeping. |

Little change to the 1-minute version apart from the colour and the stem influence: a more woodsy, herby taste. Sweetness is masked though, the whole is chunky and slightly lacks charm. |

Almost identical to the 2-minute version, as if the extraction stopped. Not very sweet and no more interest than the 1-minute. |

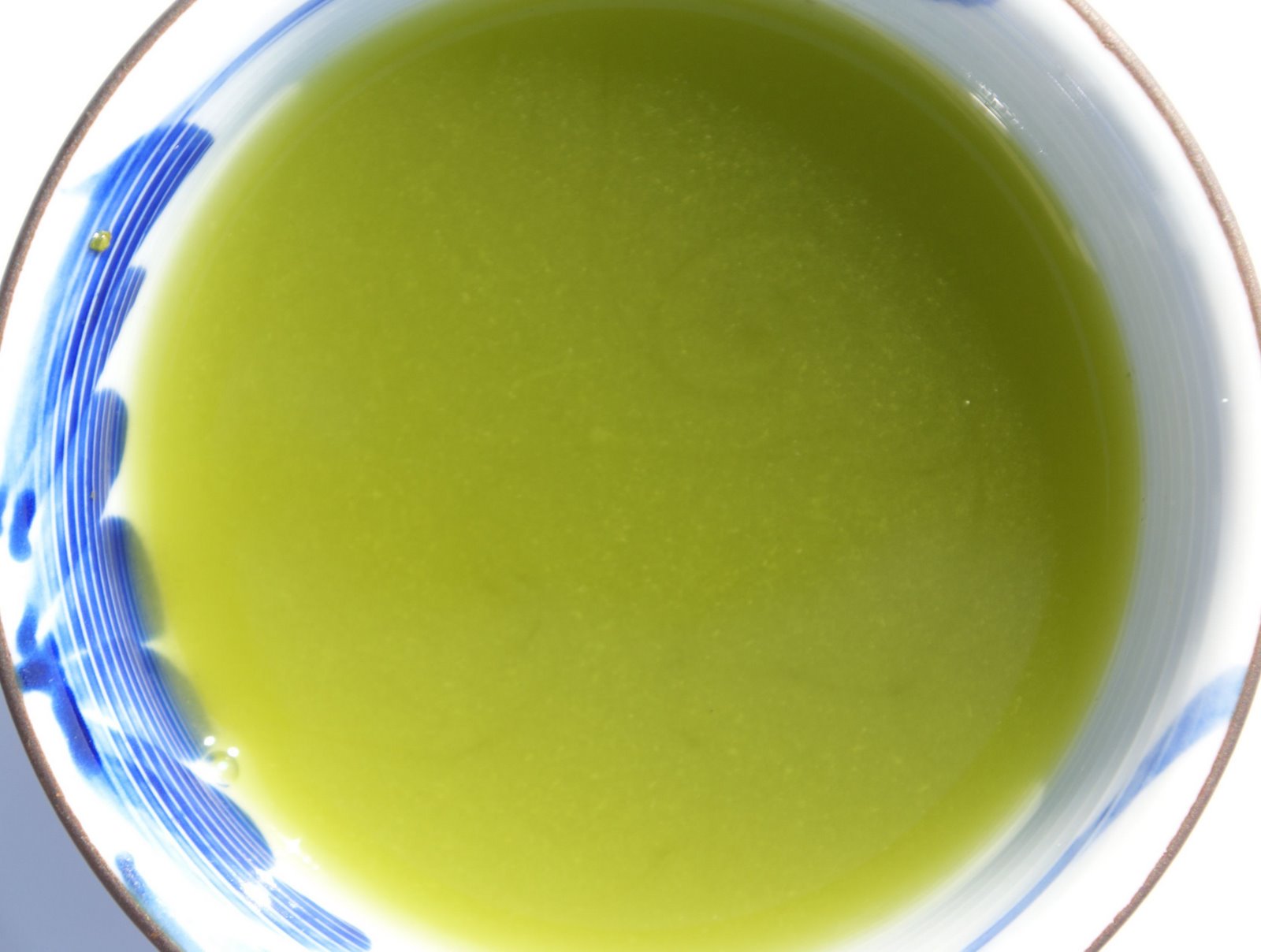

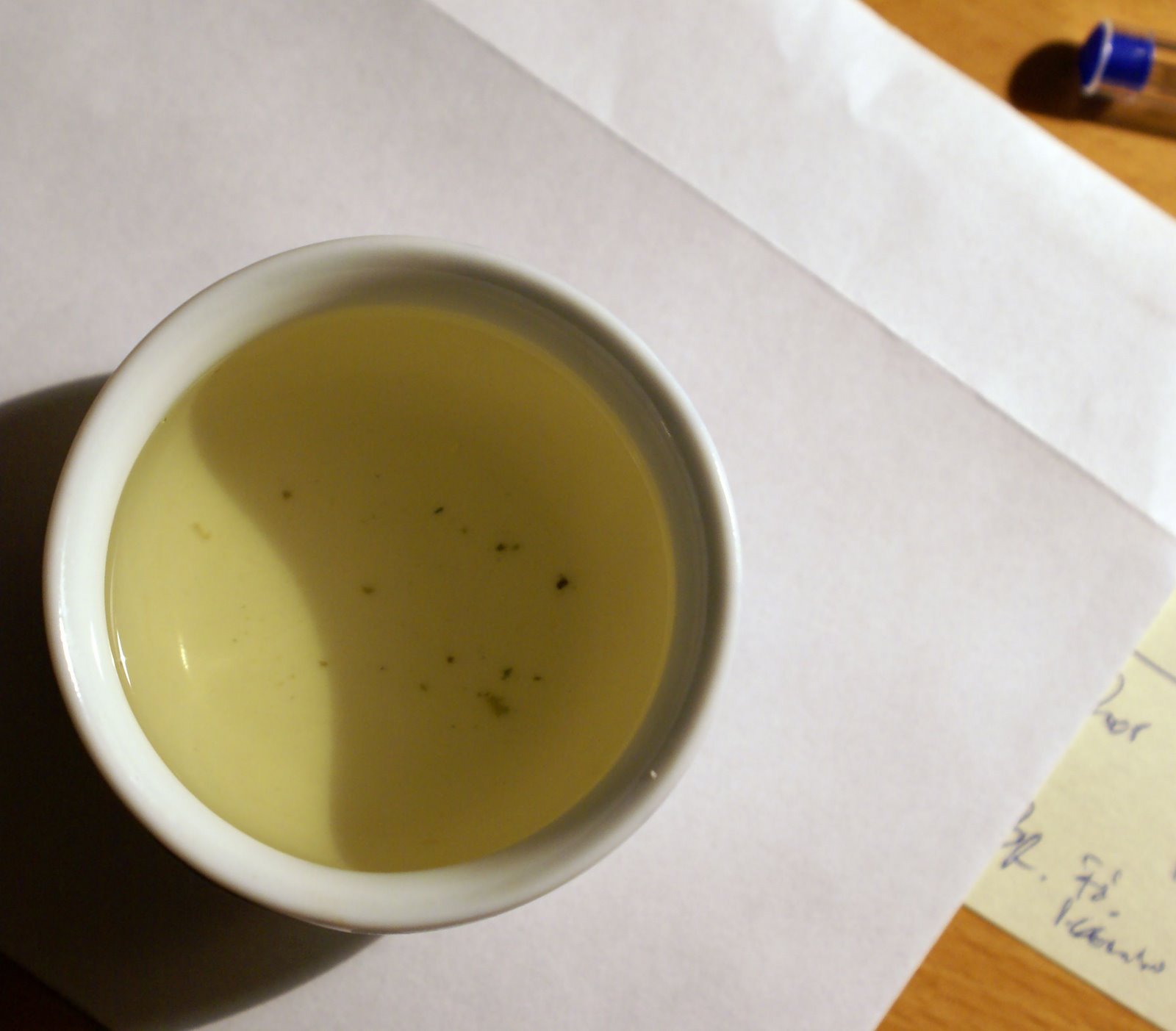

Colour of first infusion with ‘standard’ parameters (3g / 100ml / 60C / 60 seconds).

To summarise, this aristocratic karigane should be brewed like a gyokuro, with warm not hot water (55–60C seems best). 2 grams of leaf per 100ml of water is a good dosage; infusion times can vary but short ones (60 seconds) are pretty good.

This is a truly interesting tea: I can’t remember spending so much time recently with a single tea, and I hardly got bored. It shows a bit of 2008 staleness to it (I identify it as dried herbs and seaweeds) but it’s not too obtrusive. The key is to brew it properly. Done sencha-style it is underwhelming with little personality, but gyokuro-style is a completely different animal. Little aroma but on the palate this erupts with glutamic density and length, with good sweetness and an added herby dimension from the leaf. A challenging taste if you’re not ‘of the school’ but impressive for sure. And at ¥1575 / 90g can it is really good value.

Great thanks to readers who are enduring this Japanese tea marathon. We are done with sencha / shincha for now but a few more reviews are pending for other tea types. Here’s one that you don’t see often: kabusecha. Tea geeks will know it’s a style midway between sencha and gyokuro: the tea trees are shaded during the last stage of vegetation but for a shorter period than real gyokuro (days instead of months). The result is a tea that’s heftier than gyokuro but having less catechins, is less grassy and pungent than sencha. An intermediate style that’s rarely seen on sale, it is a by-product of gyokuro for some, and a distinctive tea category for others.

Marukyu-Koyamaen are selling this 2008 Takamado Kabusecha for ¥1,100 / 90g can. The dry leaf has that nice dark green colour of good quality Japanese green tea, with a bit more fragmentation than in the recently reviewed sencha from Marukyu. It’s actually looking more like gyokuro than sencha to my taste, though the leaves are larger. The aroma is quite distinctive. There’s none of the intense sweet fruit of sencha, instead the profile is very vegetal (almost spicy) ranging from olive oil to spinach.

Infusion no. 1 (60 seconds at 70C): a light colour typical of a low-steamed [asamushi] tea.

We find the latter scent again in the infused leaves: boiled spinach. Brewed sencha style (2g of leaf / water @ 70C / 1 minute steep) the flavour register is consistent with the leaf aroma: very green and vegetal, without the top citrusy notes of sencha, and not exactly ‘milder’ as people often define kabusecha. A bit of kick on the finish. Good length and an overall impression of cleanliness and very good leaf material. There’s very little bitterness even when brewed at higher temperatures, although it’s really a simple tea with no great depth.

Spent leaves show low steaming and good quality: whole and wholish leaves, no fannings.

I’ve juggled a bit with the variables here. Kabusecha being mid-way into gyokuro territory, you’re naturally tempted to brew it like the latter. While there’s reasonable texture and a kiss of umami to be obtained, this tea just lacks the guts to benefit much from higher dosage and longer infusions. On the other hand, brewing at 80C and 2–3 minutes results in a pervasive seaweedy vegetality and an almost matcha-like powderiness that shows a bit of 2008 staleness, so I don’t recommend that. It’s at its most satisfying and distinctive brewed as in the tasting note above. And it’s one tea that IMHO benefits most from a Tokoname kyusu pot, with the rough vegetal edges rounded off a bit and some extra creaminess to the texture added.

As mentioned, this is a simple, one-dimensional tea with not a lot of content, plus it’s clearly going down as a 2008. That being said, it is very good quality as all Marukyu offerings IME, is really inexpensive, and makes a fine change from your daily sencha.

The 2009 Shincha Shuei is a competition grade tea – but more knowledgeable readers will have to enlighten me as to the status of the ‘All-Japan Competitive Tea Exhibition’. In any case it’s among the more expensive offerings from Marukyu but at ¥2,600 / 100g it’s hardly exorbitant.

The good people at Marukyu seem to have a preference for asamushi [short-steamed] teas. This is another very well-presented tea with intact leaves of a consistent dark emerald green colour, no fragmentation, no fannings. Visually it is similar to the 2009 Shigaraki and 2009 Uji Gold from the same merchant I’ve reviewed before. However there is a mild variation introduced in the aroma. This tea smells almost erotic – it is so intense, sweet and creamy, full and vegetal while staying really elegant. Smelling the freshly opened can is almost as satisfying as a proper brewing session. In the background there is some very pleasant baked bread light roast.

A standard session with 2g / 100ml, water at 70C and 60 seconds for the first infusion reveals a tea that is both typical and excitingly good. The colour is medium light with as many shades of green as of gold. Flavour-wise this is eminently fresh and has so much presence and subdued, understated intensity. The concentration of a cup of tea is largely a factor of your brewing parameters but what I define as ‘presence’ is derived from the leaf quality. I rarely wax lyrical but this shincha has a haunting finesse that makes the ‘liquid jade’ metaphor sound very adequate. The leafy, spinach-like vegetality of this tea (usual in any sencha) is subordinated to its evocative character of ripe summer fruits and flowers; for me, this is the hallmark of a truly exciting tea.

First infusion with ‘standard parameters’: 2g, 70C, 60s.

In my previous post on the 2009 Uji Gold from Marukyu I mentioned that with this low-steamed category of Japanese sencha green tea, in order to boost the flavour of your infusion, you have two options to depart from the ‘standard’ sencha brewing parameters: increasing leaf dosage and/or water temperature. Applying these with discrimination, you will obtain more body and flavour without extracting too much bitterness from the leaves. (Grassy, tangy bitterness and ‘fishy’ flavours are a reason why Japanese teas – a large portion of which is long-steamed, fukamushi – are usually steeped briefly from a small dosage of leaves). With this very high-quality Shuei tea, I came up with another solution.

I’ll call it ‘gyokuro technique’, in that it consists of treating sencha tea [made from leaves grown in full sun] a bit like gyokuro [a different grade of Japanese tea made from leaves that are shaded]. In my experiment I increased dosage to 4.5g of leaf / 100ml of water and increased steeping time to 2 minutes, but lowered the water temperature to 55C. In this way, extraction of colour, flavour and nutrients from the tea is changed into a ‘softer’ but ‘deeper’ one. The colour becomes a little more intense but keeps the same greenish-golden register. The aroma is a little more intense too, but again doesn’t change substantially. The major change affects the texture. The tea becomes really thick with a glutinous, oily feel to it, and there is a very distinctive brothy, salty character that is defined as umami [the fifth taste; see more about it in this post], although it’s a little more salt-driven than umami is usually considered to be. (When discussing the concept, I’m often told I should identify it as a flavour impression independent of saltiness).

The distinctive salinity of this 2009 Shuei shincha reminded me of a great mineral white wine from such places as Cinqueterre in Italy or Santorini in Greece. Its eminent quality is also confirmed when you brew it the wrong way. Heavily overbrewed with 85C water, this is shown packing in some considerable power for asamushi, but the bitterness it develops is clean and excitingly fruit-flavoured. Whereas the similarly profiled Shigaraki Shincha from Marukyu was a very tasty but eminently simple tea this has a lot of dimension. Is it three times better as the price would suggest? No. Would I buy it again at the same price? Very definitely so.

Package aside, the dry leaves are a joy to look at:

We are on totally different territory than the trio of O-Cha releases reviewed in the last few days (see links at top of post). This is very definitely an asamushi [short-steamed] tea, and the leaves are impeccable, dark emerald in colour, 100% intact, almost exclusively whole. It’s a rare sight among Japanese teas. It has an enjoyable aroma, rather light and elegant, sweet (melon), ungrassy but vaguely reminiscent of spinach, very lightly roasted; compared to the other 2009 shincha teas reviewed in this series, this Uji Gold introduces a sweet-spicy note of vanilla.

We are on totally different territory than the trio of O-Cha releases reviewed in the last few days (see links at top of post). This is very definitely an asamushi [short-steamed] tea, and the leaves are impeccable, dark emerald in colour, 100% intact, almost exclusively whole. It’s a rare sight among Japanese teas. It has an enjoyable aroma, rather light and elegant, sweet (melon), ungrassy but vaguely reminiscent of spinach, very lightly roasted; compared to the other 2009 shincha teas reviewed in this series, this Uji Gold introduces a sweet-spicy note of vanilla. The dry leaf tells a lot about this tea’s characteristics and pretty much preannounces the ups and downs of actually brewing it. As much as I am aesthetically admirative of the leaf quality here, it’s a difficult tea to interpret. It has little to do with Japanese sencha as we know it. Brewed with standard parameters (2g / 120ml / water at 70C / 60–90 seconds) this yields a light greenish-golden colour, and the profile is very close to a continental Chinese green tea. Light-bodied, unpungent, vegetal (in the sense of green beans and spinach, not the more usual grass), with little fruit (melon); only a very minor reminiscence of brothy umami. This profile continues through the second brewing (where Japanese greens usually pack in more oomph). Perhaps a bit of creaminess to the texture (egg custard).

The dry leaf tells a lot about this tea’s characteristics and pretty much preannounces the ups and downs of actually brewing it. As much as I am aesthetically admirative of the leaf quality here, it’s a difficult tea to interpret. It has little to do with Japanese sencha as we know it. Brewed with standard parameters (2g / 120ml / water at 70C / 60–90 seconds) this yields a light greenish-golden colour, and the profile is very close to a continental Chinese green tea. Light-bodied, unpungent, vegetal (in the sense of green beans and spinach, not the more usual grass), with little fruit (melon); only a very minor reminiscence of brothy umami. This profile continues through the second brewing (where Japanese greens usually pack in more oomph). Perhaps a bit of creaminess to the texture (egg custard).

Infusion no. 1: 60 seconds at 70C.

Logically for a whole leaf tea, where the leaf surface to water ratio is far larger than in a fragmented leaf fukamushi [long-steamed] tea such as this, it’s reasonable to increase leaf quantity, water temperature, or both in order to get better extraction and more depth of flavour. From these options, a higher 80–85C temperature is fine, with more palate presence and length (but a finish that’s bit hard), but I’ve been happier with a higher dosage. Move from 2 to 4 grams of dry leaf in the pot (60 seconds for the first brewing, shorter afterwards) and you’re getting a totally different animal. Deeper in colour (though still yellowish rather than jade-green), much more saline and mineral, this reminded me of some avant-garde white wines from Alsace or Friuli in its full terroir presence. I’m interpreting this as a signature of Uji, Japan’s most renowned tea growing location. Still not exactly a typical Japanese sencha, again reminiscent of something more continental, but now a really exciting tea.

As it stands, I found this an eye-opener. Too often we are stuck with what we deem is ‘typical’: an important concept in interpreting any agricultural product but dangerous when it starts to handicap truly individual ones. This 2009 Uji Gold is precisely that: a high-quality product with a distinctive style. I’m sorry to see my 50g pack drawing to an inevitable end.

No mistake: this is Japanese shincha.

O-Cha consider this one of their best offerings. Unlike the Yutakamidori and Fukamushi Supreme that I’ve reviewed earlier (see links at top of page), this tea is from Uji, perhaps Japan’s most prestigious tea-growing appellation. At $26 per 100g, it surely has a prestigious price tag.

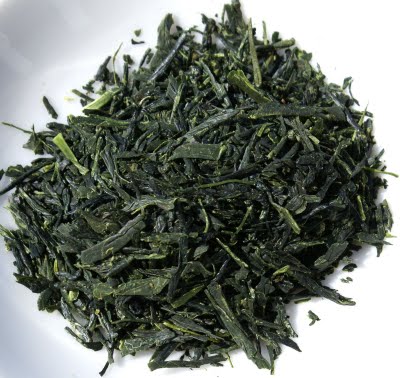

It’s interesting how I disagree with this vendor’s product descriptions. The 2009 Yutakamidori is described as heavy-steamed and this Miyabi as medium-steamed, yet there’s no doubt the latter sees heavier steaming. While the Yutakamidori, to me, is chumushi (click link at top of page to see a picture of spent leaves: there is a mixture of heavily fragmented and nearly intact that I find characteristic of medium steaming), the Miyabi is a finer fragmented tea, and it also shows in the infusion:

The dry leaf is similar to the 2009 Fukamushi Supreme in aroma, showing a larger-than-life bouquet of ripe exotic fruits that on the whole is reminiscent of a New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc; compared to the Fukamushi Supreme, it is less tangy, sweeter, fruitier (melon, papaya, some kiwi), and really tremendously enjoyable.

This aromatic register is reflected in the teacup. The scents are elegant and subtle: melon, pomelo, with an underlying vegetality. The combination of sweetness and vegetality (becoming a chewy bitterish seaweedy character when overbrewed) is also to be found in the flavour. There is nearly no astringency but quite a bit of thickness. And interestingly, the second infusion is best in nearly all my trials; while I usually rate my first infusions of Japanese greens highest, this tea is an exception. Somehow, it’s only in the second brewing that flavours seem to come together.

This tea is true to its name: miyabi, ‘elegance’. Despite its obvious thickness and a certain power it focuses around clean, elegant fruit flavours. To get the best of this character, I recommend dosing sparingly: in a comparative tasting with 2, 3 and 4 grams of leaf, the former version was the best.

Is this 2008 showing its age? Honestly, not much. It’s a clean, well-defined, reasonably complex tea of real personality, and it’s perhaps my favourite from the three sencha teas from O-Cha I’ve tried this year. But it’s even more ephemeral than the 2009 offerings from O-Cha, and its plateau of highest quality lasts only a few days from opening the pack; later, there’s a slightly drying seaweedy impression on the palate that’s a telltale sign of a Japanese green going stale. The 2009 is now available and I’m sure it won’t disappoint.

Let’s have a look at the 2009 Shincha Fukamushi Supreme. It’s another best-selling tea from O-Cha. Produced from the Yabukita varietal in the central region of Shizuoka. Priced at $23 / 100g.

Dry leaf: living up to its fukamushi [heavy- or long-steamed] name, this is very fragmented with few intact leaves. If you look at yesterday’s photo of the 2009 Yutakamidori, the difference is subtle but visible, as between chumushi [medium-steamed] and fukamushi. The most remarkable thing about this Fukamushi Supreme is the dry leaf aroma. It’s among the most intensely perfumed teas I’ve encountered. It’s a cornucopia of tangy exotic fruits, citrus, pomelo, melon, guyava, kumquat, you name it, with a subdued background grassiness and mild roast; a bouquet that positively reminds me of Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc wine from New Zealand. (The aroma also shows you how vital freshness is to this type of tea; four weeks after I opened the pack, it’s not quite the same thing, even stored in a double-lid tin).

Brewed as usually in the present series of reviews (2g / 120ml of water / 70C / 60 seconds), this tea pours a lighter colour than expected. While some chopped leaf residue makes it into the cup, the colour remains a pale green. It’s only with the second infusion (even if very short) that you get that legendary deep opaque emerald colour, like unfiltered olive oil from Central Italy:

Infusion no. 1 (60 seconds @ 70C) and 2 (25 seconds @ 80C).

The aroma is unfruity, fairly brothy, with a distinctive umami character. It’s also rather glutinous in texture from infusion #2 onwards. A dense, chewy tea with some dryness on the finish (as much a factor of astringency as texture). Interestingly, it isn’t exactly crisp, and technically has little acidity; the mouthfeel is similar to a light broth (if you cook it without lemon!) or miso soup. The melony fruit at core is soft and sweetish though, not citrusy, remaining the single fruit reference even in overinfusions at 95C. Second infusions at their densest move towards a more vegetal, chewy bean character (French beans).

Many Japanese tea drinkers have a preference for the full-on style of fukamushi teas, and I can see why this particular Fukamushi Supreme is so popular. Personally, I much like asamushi [short-steamed] Japanese greens, and so approached this tea with no positive bias. It is wholesome, of obviously good quality, and I’m perhaps doing it injustice expecting a bit more poise and zest.

As an aside, it’s one of the most short-lived teas I’ve come across, in the sense of an obvious drop in quality and complexity within a few weeks from opening the (nitrogen-filled as per O-Cha declaration) pack. While my inaugural sessions revealed some limey and grassy tang on the finish and were fairly vivid, four weeks later I am left with a simpler, flatter profile. This is understandable, fukamushi being one of the most fragmented leaf teas out there, and with the higher surface of exposure to air it just loses freshness so much more quickly than whole-leaf stuff.

As an aside, it’s one of the most short-lived teas I’ve come across, in the sense of an obvious drop in quality and complexity within a few weeks from opening the (nitrogen-filled as per O-Cha declaration) pack. While my inaugural sessions revealed some limey and grassy tang on the finish and were fairly vivid, four weeks later I am left with a simpler, flatter profile. This is understandable, fukamushi being one of the most fragmented leaf teas out there, and with the higher surface of exposure to air it just loses freshness so much more quickly than whole-leaf stuff.

Other posts in this series:

2008 Gyokuro Kame-Jiru-Shi (O-Cha)

2008 Gyokuro Tama Homare (Marukyu)

2008 Kabusecha Takamado (Marukyu)

2008 Karigane Otowa (Marukyu)

2008 Sencha Miyabi (O-Cha)

2009 Shincha Fukamushi Supreme (O-Cha)

2009 Shincha Shigaraki (Marukyu)

2009 Shincha Shuei (Marukyu)

2009 Shincha Uji Gold (Marukyu)

In the second installment of my Japanese series I have a look at the 2009 Yutakamidori Shincha from reputed online merchant O-Cha. (As an aside, I want to praise their customer service: my original $100+ order went missing somewhere between Japan and Poland, and they’ve replaced it free of charge, even shipping by EMS. It’s the sort of attitude that guarantees a re-purchase there). At $25 / 100g it is priced at the upper middle end of the range for sencha (though objectively expensive).

In the second installment of my Japanese series I have a look at the 2009 Yutakamidori Shincha from reputed online merchant O-Cha. (As an aside, I want to praise their customer service: my original $100+ order went missing somewhere between Japan and Poland, and they’ve replaced it free of charge, even shipping by EMS. It’s the sort of attitude that guarantees a re-purchase there). At $25 / 100g it is priced at the upper middle end of the range for sencha (though objectively expensive).

Other than being a perennial favourite from O-Cha and one of the more consistently high-rating tea among writers and bloggers, the interest of this tea is that it is made with a single tea variety (‘cultivar’, ‘breed’, or ‘tea tree’): Yutakamidori. While Chinese tea is more often than not a single variety product, Japanese teas are frequently blended, and when they’re not, they are predominantly from the hardy Yabukita variety, which accounts for over 80% of plantings in Japan. Yutakamidori is one of the more popular cultivars, responsible for between 3 and 5% (according to various estimates) of tea plantations. It’s a variety typical of southern tea-growing regions: this example is from Kagoshima. Yutakamidori is often described as mild and sweet, yielding a brew that’s less grassy and pungent than Yabukita.

The loose leaf is far more fragmented than the Shigaraki Shincha I reviewed yesterday. While the latter was lightly steamed, leaving the leaf reasonably intact, this Yutakamidori saw a heavier steaming that resulted in more leaf breakage and a fair amount of fannings. O-Cha are classing this as heavy-steamed, but I think it’s more towards medium steaming [chumushi], or perhaps chumushi+ as there is still some intact leaf. The dry leaf smell is very intense and delightfully fruity; from the O-Cha sencha offerings I’ve ordered this year (reviews to follow in the next few days), this is the least tangy, and the fruitiest. There’s also a mild baked bread roast to be discerned when the leaves are warmed in the pot.

Look at the colour: a clear light green-yellow, becoming only partly cloudy in subsequent infusions. It’s another shincha that is, to evoke the descriptor generally used for this class of Japanese tea, not really ‘bold’. As Yutakamidori should be, it is mild, sweet, and fruity. There is never any citric or grassy tang that I associate with tea from other Japanese varieties. Instead, the fruit register centers around melon, papaya and lychee. Later on the palate there is a mealy, grainy, cerealy, perhaps ricey impression that has a bit of umami feel to it. Brewed conservatively at 70C with a minute or so of steeping, it doesn’t really develop much in terms of bitterness or kick. It is a clean, not to say pure, tea that in my experience requires a slightly higher dosage: 2.5 or even 2.8g per 100 ml of water.

It’s a very satisfying tea, a typical chumushi with good texture. But it’s not a monster of expression or intensity: the key characteristic is balance. The high quality is emphasised when you overbrew it: it becomes bitterish and strong, but maintains the same profile and isn’t really unpleasant. It’s the first time I’m tasting this renowned tea from O-Cha, and it’s living up to its fame.

This is chumushi.

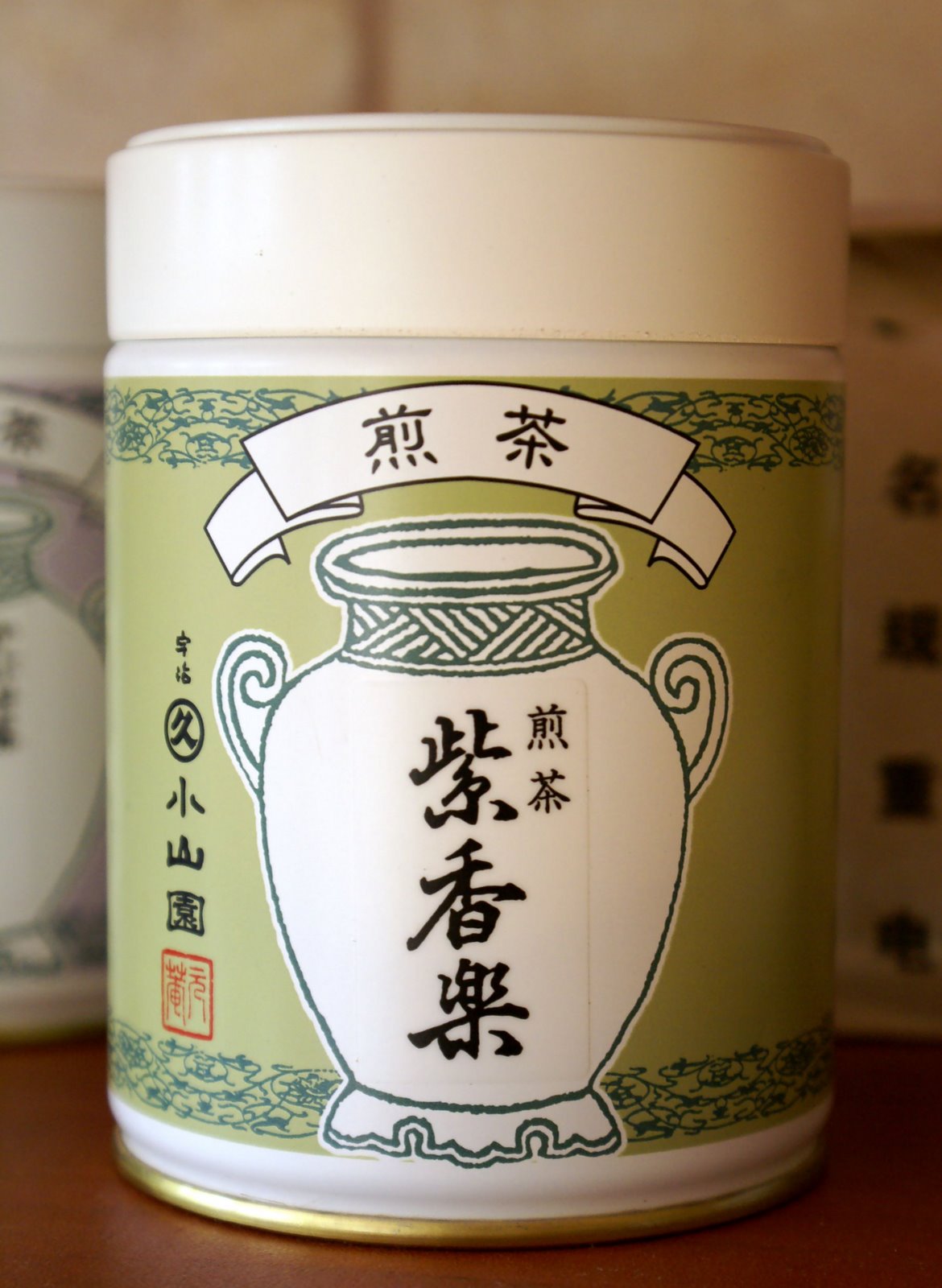

This 2009 Shigaraki Shincha is the second-cheapest from Marukyu-Koyamaen (where I’ve received excellent service, and can heartily recommend this shop). At ¥900 / 90g can (and the cans are pretty nice: see photo), it is fairly inexpensive for a quality sencha. Shigaraki is a town historically renowned for its pottery; located next to Uji, I have no confirmation whether the leaves for this tea do indeed come from Shigaraki.

This 2009 Shigaraki Shincha is the second-cheapest from Marukyu-Koyamaen (where I’ve received excellent service, and can heartily recommend this shop). At ¥900 / 90g can (and the cans are pretty nice: see photo), it is fairly inexpensive for a quality sencha. Shigaraki is a town historically renowned for its pottery; located next to Uji, I have no confirmation whether the leaves for this tea do indeed come from Shigaraki.

I have brewed this tea as all other Japanese greens in my reviews, alternating 150ml glass pot, 180ml Tokoname kyusu pot, and my favourite Korean clay pot (which you can see more extensively in

this post), dosing at 2g / 100ml and with water at 70C, 75C, 80C (I find myself stopping by the third brew almost universally with Japanese teas; the first one is almost always the most enjoyable and revealing). Where there is a deviation from this regime I will indicate this.

Brewing no. 1 (90 seconds at 70C).

Brewing no. 1 (90 seconds at 70C).In essence, this is a fairly light tea. It brews a light, transparent yellow-green colour, and is noticeably low in aroma. The flavour, however, is satisfying. No great intensity but a clean character, quite mild and unaggressive with no astringency whatsoever if brewed conservatively. It’s vegetal, leafy (but not grassy), less tangy than most sencha, with decent length. It’s not really thick but has a vaguely milky mildness to the texture, true to its asamushi peerage. Definitely uncomplex but I like it for its clean and classic profile. It’s also fairly forgiving: you really have to beat it hard on the head (i.e., going above 80C and dosing >3g) to develop any bitterness, and even then it’s of the clean invigorating kind. Shincha [first spring harvest of sencha] is often defined as bold and powerful, and tea vendors routinely warn you against overbrewing it. As with sencha, there’s a wide variety of styles and it all really depends on the region, tea cultivar, grade, processing technique etc. This tea is everything but ‘bold’, which is fine with me. For the price, it’s utterly good, and I highly recommend it.

Shincha [first spring harvest of sencha] is often defined as bold and powerful, and tea vendors routinely warn you against overbrewing it. As with sencha, there’s a wide variety of styles and it all really depends on the region, tea cultivar, grade, processing technique etc. This tea is everything but ‘bold’, which is fine with me. For the price, it’s utterly good, and I highly recommend it.

After yesterday’s post on a tea from Korea here’s another one. This 2008 Woojun (alternate spelling of ujeon, the top grade / earliest picking of Korean tea) from the Jirisan mountain is also from Eastteas. Unlike yesterday’s Nokcha, this tea is fairly expensive (£65 / 100g) but I would gladly pay double the price.

After yesterday’s post on a tea from Korea here’s another one. This 2008 Woojun (alternate spelling of ujeon, the top grade / earliest picking of Korean tea) from the Jirisan mountain is also from Eastteas. Unlike yesterday’s Nokcha, this tea is fairly expensive (£65 / 100g) but I would gladly pay double the price.

When buying Chinese tea, the earliest April flush (pre-qingming) is a reasonable standard of what you should seek and accept. Unless you’re late with your shopping and the spring teas are sold out there’s usually no problem in sourcing pre-qing stuff, and it needn’t be extravagantly expensive. At least for me, it is a good ‘normal’ grade.

Korean ujeon (which technically is the same) is a different story. Due to very low production (it makes up a fraction of Korea’s insignificant 1500 tons of annual yield) and high demand it’s a rare grade, and can get frightfully expensive. On the positive side, the quality is usually spectacular. This sample surely is.

Infusion no. 1 (45 seconds).

I have formerly enjoyed the Sparrow’s Tongue offering from Eastteas (colonial translation of jaksol or chaksol = sparrow’s tongue, a blanket term for green tea that can range in grade from ujeon through sejak down to jungjak), finding it superlatively intense and defined, and when Alex Fraser said Woojun is even better, deeper, and more intense, I was incredulous. And yet…

The leaves are really tiny (while perfectly intact). If you want to see how tiny, scroll down to the last image of this post. They indeed look like sparrow tongues or very tiny curly needles. Importantly, the dry leaf aroma is superb. It shows a very intense, distinctly herbal character I identify as oregano, with top notes of supergrade Italian olive oil. One of the best-smelling teas in my memory.

Brewing is a tricky affair. Alex Fraser recommends high dosage, low temperature and short infusions. Surely you should step down even to 50–55C for your first brewing; dosage is a matter of how you like your green tea. Using 5–6g per 100ml and lukewarm water you obtain something along the lines of a Japanese gyokuro, while I’m happy with a more conservatively Chinese-styled infusion at around 3.5g. There are echoes of the nose’s oregano and olive oil with some artichoke, the signature nuttiness of Korean green tea, and even a hint of salty umami. Outstanding character and intensity with a mouth-cleaning mentholly character on end. While it’s easy to overbrew and can become fiercely bitter, when properly handled this tea has remarkable intensity coupled with great purity. Extraordinary stuff.

This tea is made with the leaf on the right…

This tea is made with the leaf on the right…