Anniversary wines

It was the sort of event that takes weeks if not months of planning. Browsing internet wine shops, enquiring for offers, searching for tasting notes. Pondering a dinner menu, thinking of food & wine matches. Planning a proper ‘trajectory’ for the event. Alternative scenarios, ‘B’ plans (old bottles are often faulty). In the end I’m happy with how smoothly it went. With some helping hands in the kitchen I managed to serve 12 courses with matching wines to a party of 10, steering clear of major disasters. And it all took short of 9 hours.

I’ll spare you a description of the food – reading about bisques, soufflés and chocolates on a blog always sounds a little over-indulgent and of little usefulness – and share a few tasting notes.

Domaine Vacheron Sancerre 2006

This wasn’t served to guests – it was the cook’s aperitif. It’s quite ripe for a Loire Sauvignon, with subdued acidity but an obvious mineral character. A classy wine, though not a monster of expression. But I prefer Vacheron’s clean style in a less ripe vintage.

Pol Roger Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill 1993

A gift from the maison that I’ve cellared since 2003. 1993 was a structured vintage, but never great and now largely overshadowed by the likes of 1996. Yet top cuvées from 1993 are now in top shape – this Churchill surely is. Outstanding from the first to the last drop (not that it lasted long). Fresh, unevolved, poised and mineral. There is some underlying sweetness of dosage but also good vinosity and juiciness. The flavour is very fused, and it’s difficult to give a detailed analysis: perhaps a bit of raspberry atop the more usual notes of brioche and vanilla. Still very young – this can go on for another decade or two. Brilliant wine.

We’ve also had some other champagnes including a crisp, engaging Brut Réserve Rosée (two years since dégorgement) from Philipponnat, whom I find very much on the upswing of late.

Perrier-Jouët Blason de France 1959

I got this bottle from the Barolo–Brunello shop in Germany. The level was a little low and there was some heavy sediment so I knew the risk (and the very amiable owner Stefan Töpler made it clear). Such old bottles are always a hazard. Here, the cork was completely loose and the wine awfully oxidised with no bubbles. Oh well.

Domdechant Hochheimer Domdechaney

Riesling Spätlese 1983

I visited this estate on the Main near Frankfurt in April 2005, and we’ve had a great conversation with owner Dr. Franz Werner Michel. At lunch, this 1983 was served, and enhanced by Michel’s engaging stories, it tasted as good as any mature Riesling ever did. Upon saying our goodbyes we were offered a bottle each of the same wine. As usually with precious wines, it was waiting in my cellar for an ‘occasion’. A very mature wine, with some storage problems perhaps (cork was completely soaked) showing in a musty, unclean nose, though underneath there is some good Firne [aged Riesling] character. Sweeter than expected on the palate, but there is also a greenness to the sweetness and acidity. This bottle showed a bit unremarkable but was surely short of perfectly stored.

Jean-Marc Brocard

Chablis Grand Cru Bougros 1998

As expected from the youngest wine of the afternoon, no problems whatsoever with this bottle. It was part of a mixed case of older vintages I bought at the estate last October. It’s only 35€ – a bargain for a grand cru of any age, let alone a decade old. When tasted in Chablis, it showed very good saline minerality but also quite some oak sweetness. Yet served with food (a saffron-flavoured poule à la crème), the oak disappeared almost completely. It was a lesson in real-life food & wine matching. Crisp, linear, mineral, statuesque almost, showing power and reserve. An excellent wine. Dregs retasted the day after were less exciting, less poised, built around the butter and vanilla I remembered from October. Not bad at all on a hedonistic level though.

Domaine Huët

Vouvray Le Haut-Lieu demi-sec 1961

I got this bottle a couple of years ago from the excellent Bacchus Vinothek in Germany. The price seemed low (50€), and these Vouvrays are known for their ageing potential so I took the plunge. Looking at the intact label and the immaculate cork it’s clear this bottle was at best recorked (and likely refilled?), and at worst it’s not a 1961 at all. It’s an excellent aged Vouvray but it really tastes too young and dynamic to be 48 years old. The colour is also a bit suspect, with green tinges (unlikely in a wine of this age?) to a medium golden whole:

Aromatically it’s dominated by a taut, austere reductive character: not quite stinky but very herby and hayey, with a bit of richness that reminded me of an old Tokaj. On the palate it is very structured with mouth-puckering acidity effectively covering the sweetness, although the demi-sec character is quite pronounced for a wine of this alleged age. There’s also some alcohol (only 12% on the label). A big, structured wine that’s fairly immobile and could easily survive another decade. If you don’t need it to be a genuine 1961 it’s a very fine bottle for the money.

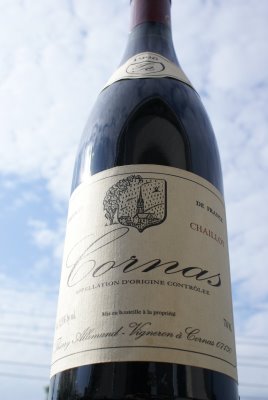

Thierry Allemand Cornas Chaillot 1996

A bin-end from Vienna’s Unger & Klein, sold at 32€ instead of the more usual 60€. Deepish colour especially at core, for the age. It starts fairly barnyardy and reduced on the nose but fortunately isn’t bretty, and with some proper airing this blows off, revealing a fairly engaging nose of crushed raspberries and good vinous depth. Some mild age on the palate but this is far from old. Palate on entry is also pleasant: vaguely varietal and peppery, but the progression is highly disappointing. Basically this just weakens and disappears on the palate. No structure whatsoever: modest acidity (though enough for freshness) and no tannins. There’s a beguiling purity about the whole thing and I can’t say it’s uninteresting but I wouldn’t pay the normal price for it. Perhaps the vintage’s lowly reputation in the northern Rhône is justified after all.

Cosimo Taurino Brindisi Riserva Patriglione 1975

This was another bin-end from a German shop, so obscure they didn’t even know how to price it. Eventually I got away with 35€. In its recent vintages it’s a southern Italian classic I very much enjoy, essentially a modified Salice Salentino (based on the Negroamaro grape) made with an amarone-like technique of drying the grapes to raisins. Fill level is quite and the cork is excellent (certainly recorked) but storage is an issue, as the wine is showing very aged. There’s a leathery, cooked-fruity, vinegary, almost maderised character that some of my diners disliked, though with a bit more experience in Apulian wines I find it fairly typical. This has aged on acidity (and some greenness) but lacks superior dimension or definition. On the other hand a Brindisi red at age 33 in this shape is surely not a bad achievement.

Giacomo Borgogno & Figli Barolo Riserva 1947

It’s another Barolo–Brunello bottle from Stefan Töpler. I paid 149€ for it and whenever I can justify the expense again, I’ll be sure to order some more – an outstanding bottle of wine.

I have had numerous older Barolos from the house of Borgogno, including a fantastically refined 1958, an impressive, brooding 1961 and a gentler 1967. But all came from the producer’s cellar, and were all opened and checked for faults, then refilled with the same wine, recorked and relabelled. Basically you get a Borgogno guarantee that the wine is in good shape. This makes the producer’s prices (the 1961 was 105€ a year ago) even more of a ridiculous bargain.

The one disappointing thing here is the nose. I usually enjoy Barolo as much for its fantastically floral, deep bouquet as for anything else, but here it’s a little lifeless, showing modest notes of raspberries, dominated by a green, briney, animal, damp-cellary, mildly over-the-hill character. But palate is very fresh and alive, with beguiling coffeed complexity. Very good length too. Perhaps not the ultimate Barolo experience (1961, with its remaining power, is more impressive) but very interesting for sure. Last sips at room temperature are really tannic (!), mineral, impressively long and so very much alive.

The one disappointing thing here is the nose. I usually enjoy Barolo as much for its fantastically floral, deep bouquet as for anything else, but here it’s a little lifeless, showing modest notes of raspberries, dominated by a green, briney, animal, damp-cellary, mildly over-the-hill character. But palate is very fresh and alive, with beguiling coffeed complexity. Very good length too. Perhaps not the ultimate Barolo experience (1961, with its remaining power, is more impressive) but very interesting for sure. Last sips at room temperature are really tannic (!), mineral, impressively long and so very much alive. Kopke Porto Colheita 1938

Kopke Porto Colheita 1938A half-bottle that was distributed to journos who attended a presentation of old colheita ports from the Sogevinus companies (a holding that was established in 2006 and regroups some of the most prestigious port brands: Barros, Burmester, Cálem and Kopke). No bottling date but likely to have been 2007, shortly before the event. Colour is a transparent brown-amber. For volatility and a salty, marmitey character this is close to a madeira in style. A vestige of pink fruit, crystallised sugar, minor saltiness underneath; not really nutty (unlike most of these old colheitas). Moderate sweetness, high acidity, good (but not extraordinary) length, this is a good example of an aged colheita but frankly unexceptional. The flavour is a bit low and there’s only reasonable complexity; this tastes like a mid-1970s colheita could (and not a greatly structured one at that). Perhaps just an inferior vintage here, as the 1937 was one of the stars of the said tasting.