Overbuying tea is commonest of vices. Tea is cheap (mostly), vendors carry a large range of potentially interesting stuff, and then tea comes from far away where shipment often makes up a large portion of your payment (so it’s sensible to buy a bit more than you would from a shop next door).

I ordered a dozen samples of aged puer from Nadacha in the summer, hoping to go through them in a few weeks and perhaps make some buying decisions. But soon afterwards I had four orders of 2009 Darjeelings, then a large batch of Taiwanese teas from Teamasters, and now I’ve just bought two dozen 2009 puer cakes from Yunnan Sourcing. And so the time to taste through the Nadacha samples has been very little!

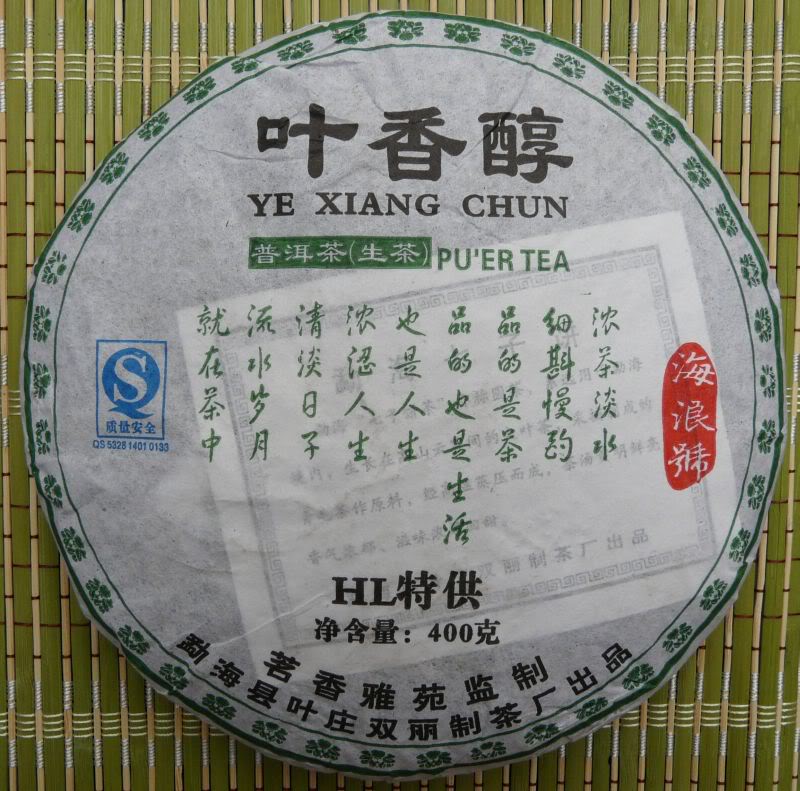

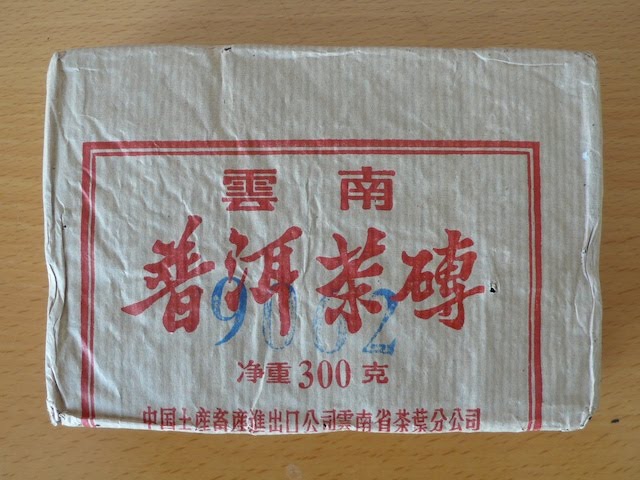

I must make it a commitment for 2010 to buy less tea and be more systematic in my tasting. I’m toasting to this ambitious undertaking with this 1990 Menghai #9062 Brick (see Nada’s product description). At £78 it’s a fairly inexpensive tea for its age and producer; this is because the brick itself is a mixture of sheng [‘green’ puer] and shu [‘ripe’, or artificially fermented, puer], lacking the dimension and complexity of a true sheng.

Let’s look at the leaves. They are fairly dark, with minor amount of white ‘frosting’ of age, and have a faint smell: cavernous shicang [‘wet storage’, fermentative aromas] and decomposed wood. The spent leaves are interesting to look at: you can clearly see the mixture of sheng (the larger, dark brown leaves that unfold completely) and shu (darker, almost black leaves that remain rolled). Both components look like a reasonably high grade, with large, good quality leaves of which many are still intact; the shu leaves are not the usual non-descript mulch. The mix is quite rustic, however, including a generous helping of twigs and stems.

I’ve brewed this tea several times with different techniques, and can say it’s quite unsatisfactory with long steepings. Anything beyond 30 seconds for your first brewing will result in a very wet storage-dominated profile with a vegetal decomposed-wood bitterness on end I’ve found unpleasant.

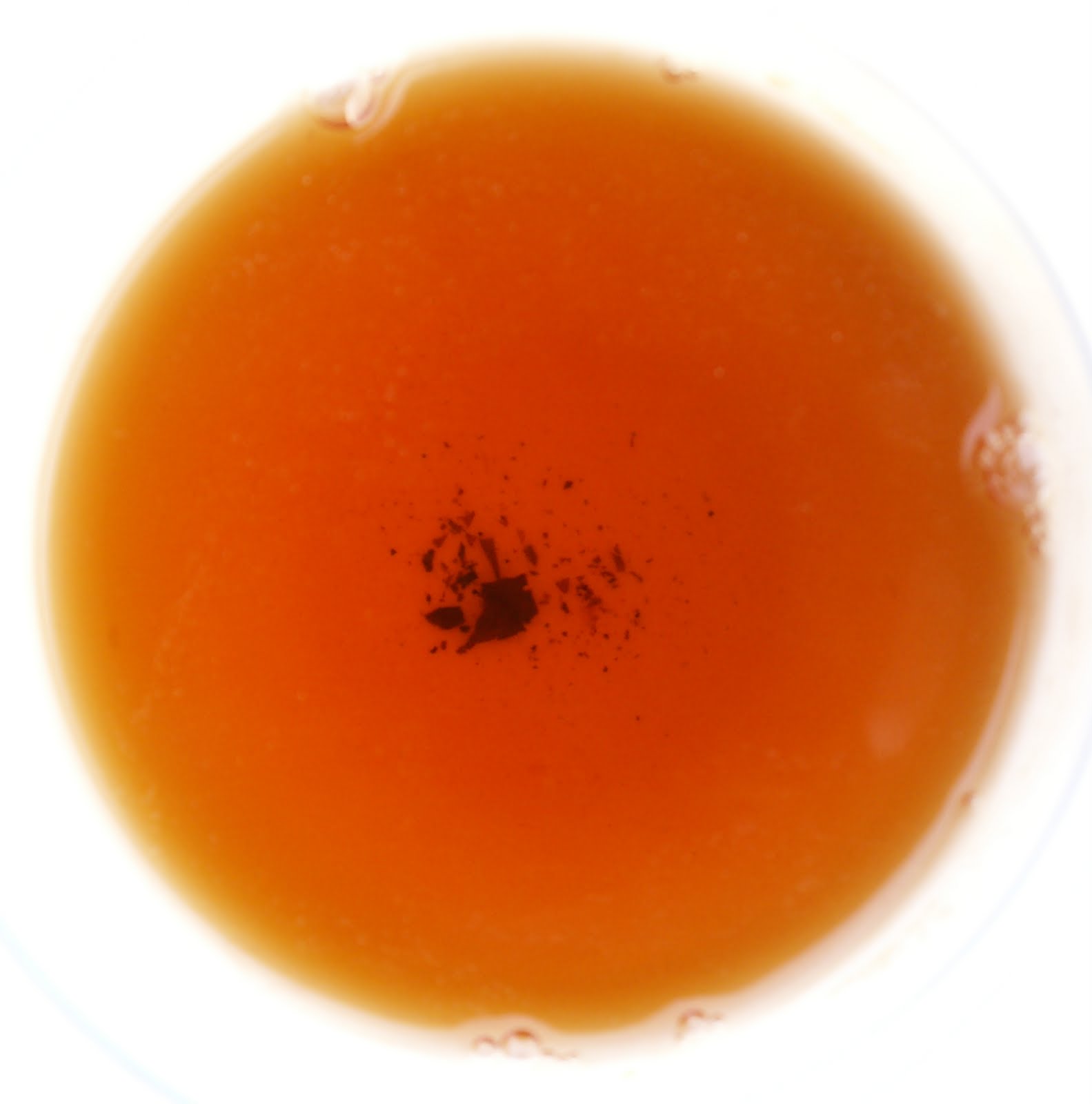

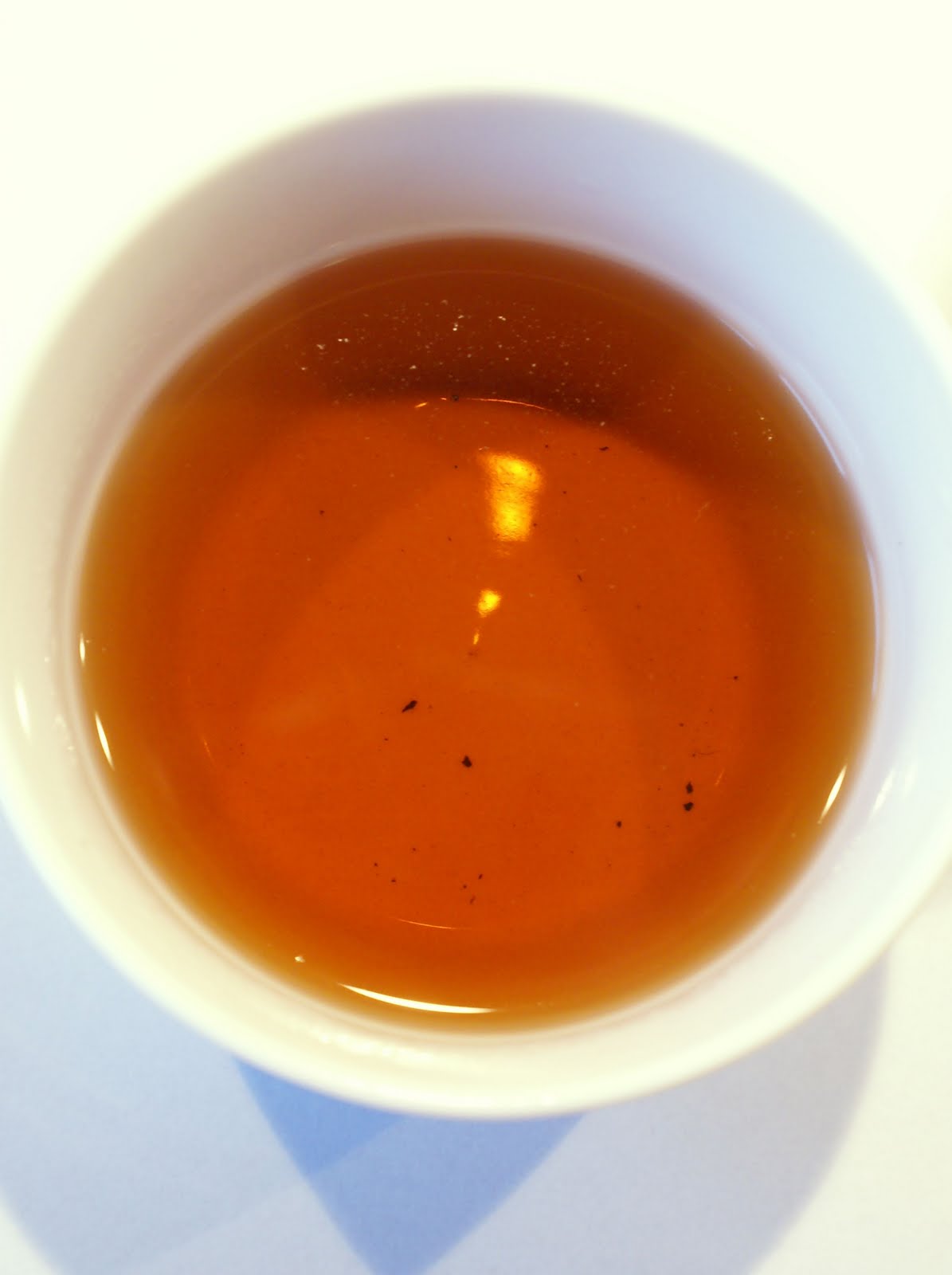

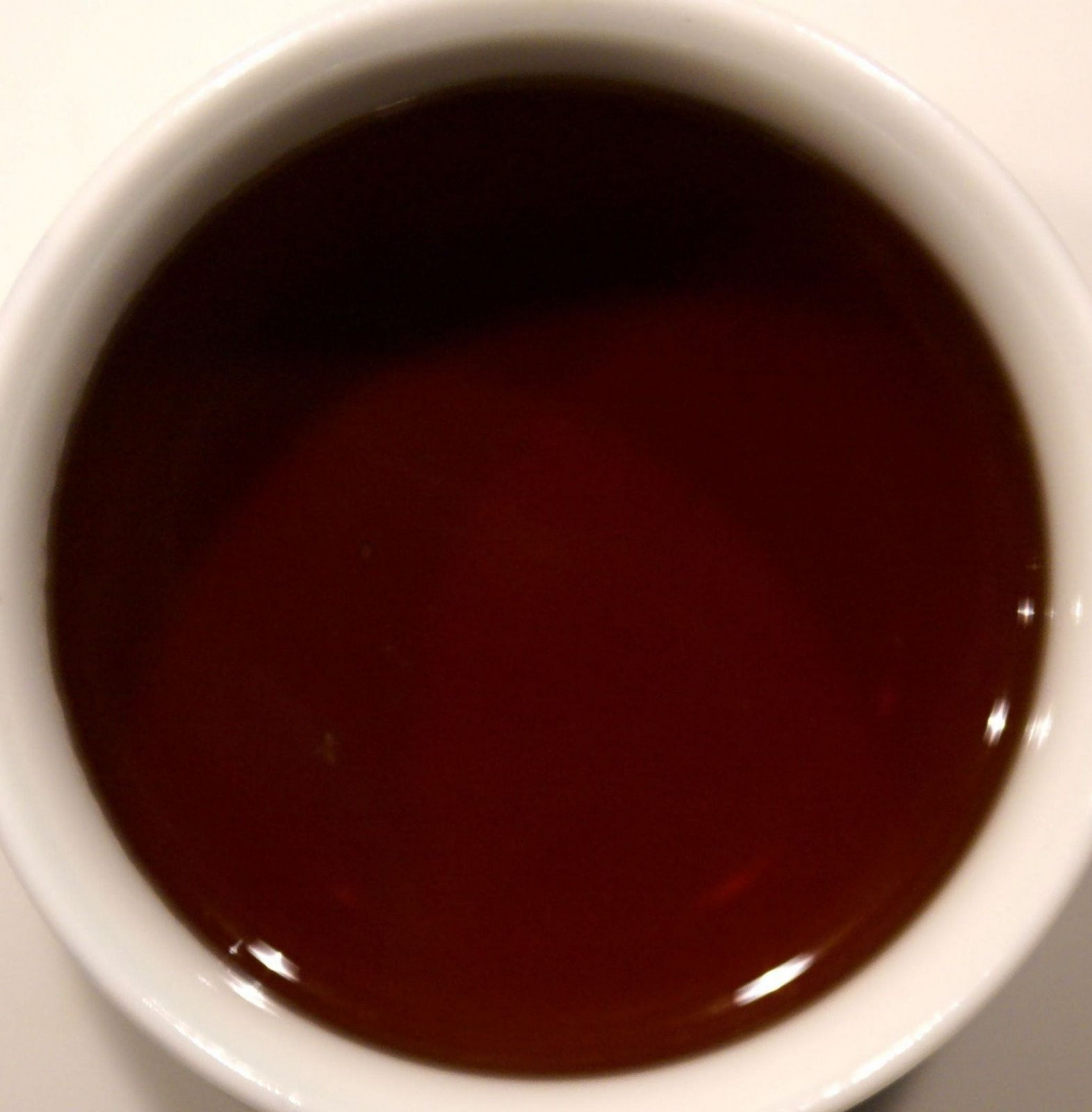

The best approach to this tea is a classic gongfu series of short brewings in clay pot (I’ve dosed exactly 5.2g of leaf for 120ml of boiling water, rinsing once and brewing 15s, 15s, 25s, 30s, 30s, 40s, 3m). It’s hefty, powerful tea, delivering quite a bit of colour from the beginning, and a good intensity of wet storage-driven, stoney, mineral, woody taste. The first brewing also provided a nice warm mealy, fat textural touch, but afterwards the tea failed to deliver this promise and showed rather one-dimensional.

First infusion (15 seconds) in yixing teapot.

It is quite unaromatic, and even using an ‘aroma cup’ that usually helps to magnify the bouquet only resulted in an interesting first progression from shicang through toasted grain to caramelised sweetness; subsequent infusions were pale and uncomplex.

This tea is not very patient, as soon as the 7th infusion it’s become quite unintense and losing interest. Even though short steeps help control the vegetal bitterness on the finish, it’s still there in varying proportions, and is my greatest criticism about this tea. Although quite aged, it still has power left, and the sheng and shu elements are by now nicely fused, but there is no complexity or structure and essentially the tea has little to offer beyond its chunky shu-driven power.

It’s an interesting opportunity to taste a mature tea from a leading producer but I feel no need to go beyond my 15g sample.

Disclaimer

Source of tea: own purchase

This is an extraordinary creature of a tea. Looking at the expired leaf (see photo above and below), there are still lots of intact whole leaves after 20 years! Really thick with very developed veins. This tea abounds in rough, elemental power, making it easy to believe the declared ‘wild tree’ provenance (how many modern puer can you say this about?). In purely drinking terms, it may lack the elegance (or ready-to-drinkness?) of the

This is an extraordinary creature of a tea. Looking at the expired leaf (see photo above and below), there are still lots of intact whole leaves after 20 years! Really thick with very developed veins. This tea abounds in rough, elemental power, making it easy to believe the declared ‘wild tree’ provenance (how many modern puer can you say this about?). In purely drinking terms, it may lack the elegance (or ready-to-drinkness?) of the