Indulgence

Toasting the New Year with… Bordeaux.

Toasting the New Year with… Bordeaux.

There are two types of wines that could hardly be held in higher esteem by wine journos, and yet are quite unpopular with the wider drinking ‘public’: dry sherry and dry Riesling. I can recall the names of at least a hundred colleagues who have sung the praise of Jerez seco and Riesling trocken. ‘The wine world’s best-kept secret’, ‘ridiculously good value’, ‘when will humanity open its eyes to the greatness of these wines’ etc.

There are two types of wines that could hardly be held in higher esteem by wine journos, and yet are quite unpopular with the wider drinking ‘public’: dry sherry and dry Riesling. I can recall the names of at least a hundred colleagues who have sung the praise of Jerez seco and Riesling trocken. ‘The wine world’s best-kept secret’, ‘ridiculously good value’, ‘when will humanity open its eyes to the greatness of these wines’ etc.

While dry Riesling in the last few years has made significant inroads and now can hardly be said to be ‘unpopular’ (although it still loses to sweet Riesling on such markets as the US and the UK, I think), dry sherry remains a commercial disaster that’s only surviving thanks to sales of the lightest style, fino sherry in Spain and abroad. The longer-aged, more complex styles like amontillado, palo cortado and especially oloroso are an acquired taste and have been relegated to a shrinking niche.

I don’t drink enough of these (supply in Poland is non-existent), and every time I do, I’m reminded how much I’m missing. These wines belong to the most compelling anywhere. But I’m also reminded how difficult it is to appreciate them from time to time. Delving into these deeply oxidised, unfruity, nutty, at times challengingly acidic and salty flavours requires a complete reset. If you open a bottle of oloroso between a Chardonnay and a Rioja, chances are you’ll find it repulsive. It really needs to be a regular exercise. There’s also no way to forget their alcoholic strength: while the 20% in an oloroso are as balanced as you’ll ever find, it’s not a wine you can drink in quantity, also because it’s so intense and mouth-filling.

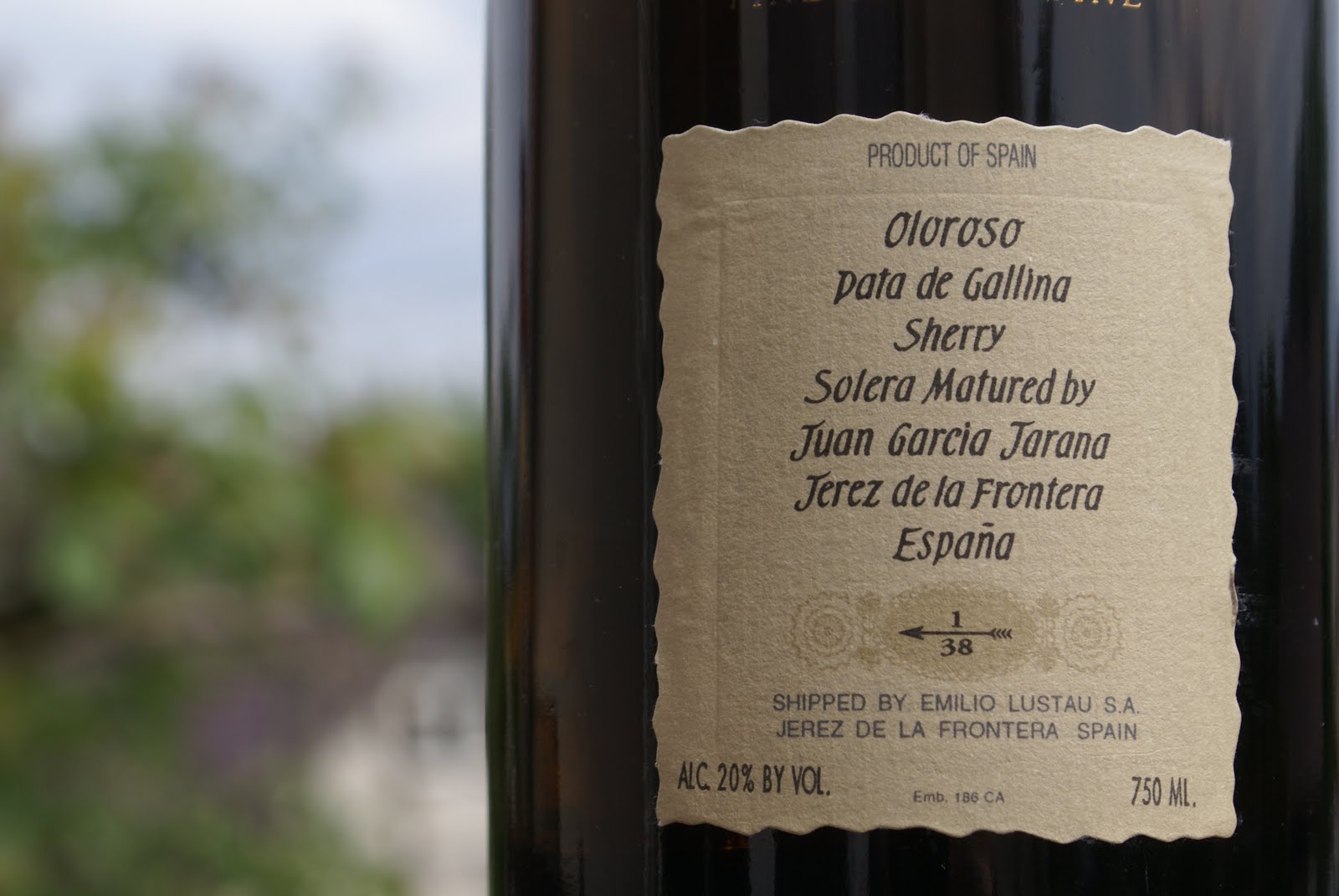

The bottle I’m having today is among the very best sherries available on the market. From the négociant house of Emilio Lustau comes this Oloroso Pata de Gallina 1/38, matured by Juan García Jarana. I’ll spare you the technicalities (it’s basically a micro-production from a single grower, which is a very unusual thing in the world of sherry, normally a classic blended and branded wine) and will just say it’s a mindblowingly complex wine. I could write page after page of aroma descriptors and wouldn’t be exhaustive. There’s a unique combination of almondy, nutty, marzipanny, wafery, pâtisserie notes with nuanced fruits ranging from orange and lemon to raspberry, heavier spicy notes of mulled wine, bitter chocolate and caramel, a raisiney richness but also lots of lifted, sandalwoody, varnishy, almost vinegarish scents. But it’s all in balance. It’s a wine that keeps changing in the glass: over half an hour it’s really like an aromatic journey over an amazingly complex landscape. I sit in silence and awe as the wine tells its epic story.

The other remarkable thing is that I’m finishing this bottle that was opened on 30th December 2007. That’s no joke. December 2007, not 2008. That’s 596 days! And I must say the wine is still very much alive. I can’t say it’s unchanged – it has surely lost some complexity – but is still offering more than a fair bit of impact, and length is as staggering as usually in a good oloroso. The wine was completely oxidised in oak barrels over something like twenty years (it’s hard to give a precise period of ageing, as the barrels were regularly refreshed with new wine) and it really couldn’t care less about being exposed to oxygen now. Only madeira can approach this durability. It’s making this wine even more unique. Please drink more dry sherry!