A vertical of Roda I

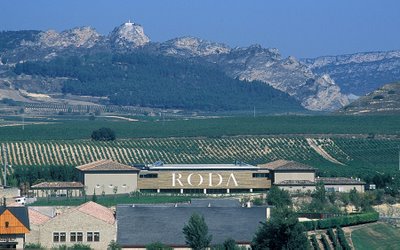

© Manel Armengol / Roda S.A.

The latter element was certainly confirmed by our vertical tasting. None of the wines showed even remotely tired, and even the 1992 (hardly a great vintage in Rioja) held tremendously well for four hours from opening, staying deliciously fruity and fresh. Among the older wines 1996 was very bretty and a little blunt but otherwise showed the customary Roda concentration and balance; 1997 was a little lighter than its siblings with notes of red fruits, and while a little simple it too retained power throughout the evening, showing well with food. All were towered by the outstanding 1994, staggeringly young and tonic, with lots of extract and austerity and no hint of maturing. It just lacked a bit of finesse and allure to be perfect but it was a very big bottle indeed.

But there were problems, also. Two bottles of the 1995 were corked (a pity; I’ve enjoyed this vintage in Rioja), and two of the 2000 were oxidised. The 1998 scored very highly upon opening for its ‘Burgundian’ (my colleagues’ term; I disagreed) architecture but the obvious lack of structure made for a less than convincing evolution in the glass; it was massacred by a beef steak. The 1999 didn’t quite convince, so modern and creamy-oaky it still was after seven years in bottle; perhaps just a problem of middle age.

And then the latest vintages continued along very controversial lines. 2002 was predictably lighter but not light enough; a rainy vintage that was a good occasion to tune down the extract was in the end made a replica of 2001. 2003 was simply port-like in its extravagant alcohol and notes of stewed fruit – unsurprisingly so for 2003 but that’s hardly a consolation. The 2001, once described by a Roda representative as ‘the very best since 1964’, was heavy, chocolatey, alcoholic and unremarkable (though to its credit, it evolved well in the glass). Eventually I preferred the very balanced 2004, although there was no escaping the 14.5% alcohol and the creamy milkshake textural feel to the overvatted tannins.

Proceeding from the older vintages through to the latest ones, this was a puzzling tasting. Normally when I look at new Roda releases (usually at least once per year), I really like the wines and don’t mind the style all that much, although 1) I have always preferred the lighter, juicier, less ‘ambitious’ Roda II (now called Roda Reserva), and 2) the Cirsión supercuvée, which is made along the same lines as the Roda I but multiplied by two, I have usually found an excessive and unsympathetic wine. Yet this vertical tasting magnified the stylistic problem of the latest vintages. Instead of the former 13.5% alcohol we now have 14–14.5%, and while Roda has never been a high-acid wine, significantly I used the word ‘fresh’ in my tasting notes for all vintages through 1997 but ‘soft’, ‘creamy’ and ‘blunt’ for all since 2001. This is arguable but in my book Tempranillo really doesn’t take late harvest very well, and I actually prefer it a bit on the green side, especially when it has many years to mature to integrate that greenness.

In the end Roda I is a prestigious bottling that deserves the benefit of a doubt, and you might say the successful recent vintages like 2001 and 2004 are likely to evolve along the same lines as the 1994 or 1996. But noticing this subtle stylistic change, I doubt they will.

© Manel Armengol / Roda S.A.