Memories of 2013

My best wines, places, and people of 2013.

My best wines, places, and people of 2013.

Greetings from Slovenia – a neat, efficient, fascinating country.

Comments on blogs that are surprisingly informed and relevant… but are posted by robots.

No relation to the wine in your glass? On the very contrary; the genetic diversity of our grape varieties is a crucial issue for the future of viticulture and winemaking.

Disclaimer

Accomodation during my stay in the Wachau is paid for by the Austrian Wine Marketing Board. All wines were provided by the producers.

Pre-opening photos of the brand new Chopin Museum in Warsaw.

Two hundred years ago from today, a shy boy was born.

But in my case, the tea had to be special. With so many old wine vintages being poured, I wanted a tea with several decades on it. Old puer was best avoided, though, as the taste could be challenging to some diners. So I went for this 1976 Baozhong from Tea Masters (see description here

; the tea is out of stock at the moment, although Stéphane says it might be available again in the autumn).Last week’s anniversary dinner was an eye-opener for this Baozhong, after circumstances forced me to change my brewing style. To accommodate so many people, I had to choose a really large pot. My choice went for this glass pot which contains roughly a liter:

It’s the equivalent of what is called ‘glass brewing’ or ‘bowl brewing’ (see discussions here

Looking at the wet leaves, it’s no surprise this tea is so good. The roast has been really virtuosic as many leaves are still dark green in colour (have a closer look at the twisted leaf to the far right of the photo below). And for their age, they are really impressively intact. On top of it, it’s a really inexpensive tea for its age (40€ / 100g). Dear Stéphane, I truly hope you can source some more!

Looking at the wet leaves, it’s no surprise this tea is so good. The roast has been really virtuosic as many leaves are still dark green in colour (have a closer look at the twisted leaf to the far right of the photo below). And for their age, they are really impressively intact. On top of it, it’s a really inexpensive tea for its age (40€ / 100g). Dear Stéphane, I truly hope you can source some more!

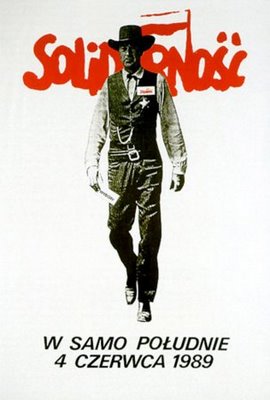

A famous 1989 poster by Tomasz Sarnecki.

Today’s a big day for Poland. Two decades ago, on Sunday 4th June 1989, the first free elections since World War II were held, resulting in a landmass victory for Solidarity and effectively putting the Communist regime to an end. Other countries of the ‘Eastern bloc’ followed suit. Five months later, the Berlin wall was demolished, and two years later, the USSR ceased to exist.

In this day of pride and satisfaction, we look back at that amazing summer of 1989 and what we’ve been able to achieve since. Among many far more serious things, we can enjoy a boundless diversity of wines, buy tea directly from Taiwan on the internet, develop private breweries and buy the latest music CDs in a range of high-street shops. Many things wouldn’t exist without Poles going to the polls two decades ago, including this blog.

Between 8 and 8:20pm today, all across Poland people raised a toast to our happy past and, hopefully, auspicious future. Chez Bońkowski, it seemed suitable to do so with a wine from our Slovenian brothers-in-freedom. The Dveri-Pax Eisenthür 2005 is a wine that couldn’t have happened two decades ago. Slovenia was still part of a country called Yugoslavia, where wine could only be bottled and sold by state-controlled cooperatives. Now this historical estate in Slovenian Styria (it was founded in the 12th century as a Benedictine abbey) has been reprivatised and with a large investment, vineyards have been renewed and a new state-of-the-art cellar established. The first wines were released in 2002 and Dveri-Pax quickly confirmed its rank as one of the leading wineries in Slovenia.

This 2005 Eisenthür single vineyard wine is a blend of 70% Sivi Pinot (local name for Pinot Gris) and 30% Šipon (local name for the Hungarian Furmint), and weighs in at 12.5%. A little capricious at first, it really gains from some airing, showing a very clean minerality from the strong volcanic terroir. It is quite Austrian in style (back in 2005 the winery’s consultant was Erich Krutzler from the famous red wine estate in Burgenland, now making wine at Weingut Pichler-Krutzler) with ripe green fruit and a clean, zesty style. It’s not a great wine, showing a bit of dilution and underripe greenness – but bear in mind 2005 was a fairly difficult vintage in this part of Europe, and the wine is fairly balanced with a good sense of place. Even its imperfections seemed to fit in today’s mood of Central European celebration.

My green teas from 2008 have to move out quickly to make room for 2009s. Longjing, Biluochun, Sencha are all being harvested at the moment, and some are ready for immediate EMS shipment.

But drinking tea up is no easy task. Any tea lover will know the embarras de richesse of a drawer full of samples. With 70 at this moment, I think I am among the least overstocked. Some teas can age, of course, and these will be happy with a few months’ oblivion as I delve into newly delivered 2009s. But fragile green teas – especially those from Japan, in my experience – should ideally be consumed within the year of harvest.

Today’s is definitely a belated note, then. The 2008 Harayama Shincha was made with the first spring harvest of last year. Shincha – ‘new tea’ – is often nicknamed the Beaujolais Nouveau of the tea world. It is equivalent to what the Chinese classify as pre-Qing Ming (or ming qian): the first spring buds plucked before this major Chinese festival that usually falls at the beginning of April. So in essence, this Harayama (a prestigious origin in the prestigious region of Uji) is an early harvest sencha Japanese green tea.

Merchant: Eastteas

Price: £16 / 100g

Brewed in: Korean clay cup (see photos)

Dosage: 4g / 120ml

Leaf: Immaculate elongated pressed leaves boast an impressively consistent dark green. This clearly belongs to the light-steamed family of Japanese tea (a.k.a. asamushi). I somehow found these wonderful leaves representative of the perfectionist Japanese aesthetics. Dry leaf smell is a concentrate of vegetality, with notes of asparagus, artichoke, and especially extra virgin olive oil.

Tasting notes:

1m @ 70C: A typical pale golden / celadon colour. The nose is quite aromatic with a top note I identified as nutmeg. Body is round and flavourful, allying sweetness with vegetal freshness, losing its bite gradually as there is very little overt grassiness: this is true to the shincha sort in being airy, light, without the tang of full-season sencha.

30s @ 70C: Good character, if a little less intensity than the first brewing. With fruity notes a bit lower, the full glutamic scharge is arriving with more power. This tea is easy to overbrew (in fact brewing at 85C results in too much astringency) but if you find the right balance it is really delightful.

80s @ 80C: Now slowly eclipsing into a vague greenish soup. Still pleasant but with limited interest.

Overall this tea has held reasonably well (my notes from November 2008 and this morning are consistent), and although hardly complex, it really delivers very good intensity of spring leaf flavour. Just what shincha should be. I can’t wait to receive my 2009s!

I also draw your attention to the lovely tea items on the photos (also purchased from Eastteas). The handy crackled celadon clay pot and accompanying cup are by Korean potter Mr. Bo Hyun, and have an effortless elegance while being very practical for brewing a single cup of green tea (especially fragmented-leaf, as in this case). The carved wooden tray is my Mr. Kang. It is perfect as a small tea table for one, or for serving three or four guest cups on.