Best wines of ProWein 2016

The emotional moments of ProWein—from Champagne to 100-point vintage port!

Why are cheap Spanish wines better than the more expensive ones?

Fresh and fruity. I need nothing more at 5.90€.

Toasting the New Year with… Bordeaux.

There are two types of wines that could hardly be held in higher esteem by wine journos, and yet are quite unpopular with the wider drinking ‘public’: dry sherry and dry Riesling. I can recall the names of at least a hundred colleagues who have sung the praise of Jerez seco and Riesling trocken. ‘The wine world’s best-kept secret’, ‘ridiculously good value’, ‘when will humanity open its eyes to the greatness of these wines’ etc.

There are two types of wines that could hardly be held in higher esteem by wine journos, and yet are quite unpopular with the wider drinking ‘public’: dry sherry and dry Riesling. I can recall the names of at least a hundred colleagues who have sung the praise of Jerez seco and Riesling trocken. ‘The wine world’s best-kept secret’, ‘ridiculously good value’, ‘when will humanity open its eyes to the greatness of these wines’ etc.

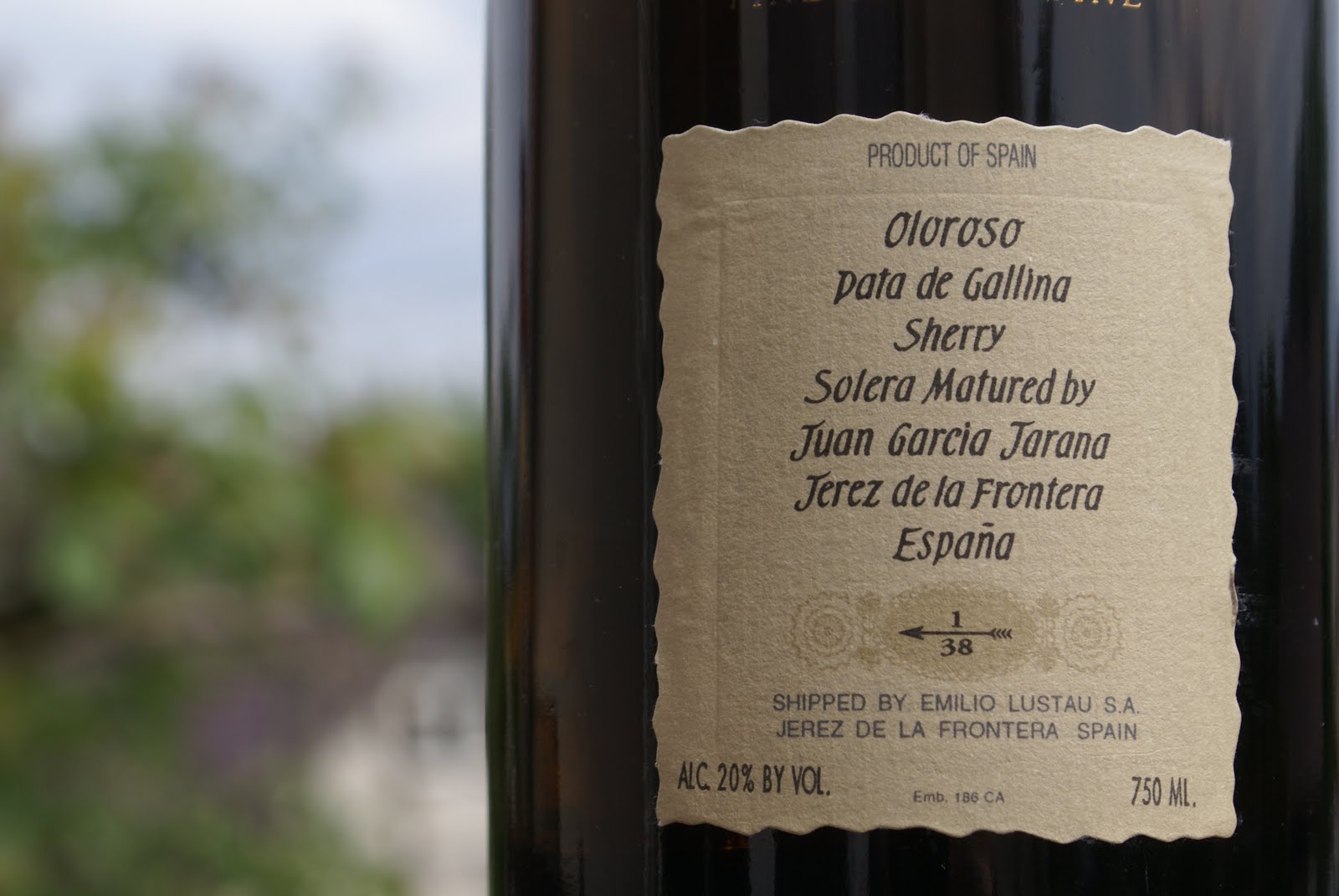

While dry Riesling in the last few years has made significant inroads and now can hardly be said to be ‘unpopular’ (although it still loses to sweet Riesling on such markets as the US and the UK, I think), dry sherry remains a commercial disaster that’s only surviving thanks to sales of the lightest style, fino sherry in Spain and abroad. The longer-aged, more complex styles like amontillado, palo cortado and especially oloroso are an acquired taste and have been relegated to a shrinking niche.

I don’t drink enough of these (supply in Poland is non-existent), and every time I do, I’m reminded how much I’m missing. These wines belong to the most compelling anywhere. But I’m also reminded how difficult it is to appreciate them from time to time. Delving into these deeply oxidised, unfruity, nutty, at times challengingly acidic and salty flavours requires a complete reset. If you open a bottle of oloroso between a Chardonnay and a Rioja, chances are you’ll find it repulsive. It really needs to be a regular exercise. There’s also no way to forget their alcoholic strength: while the 20% in an oloroso are as balanced as you’ll ever find, it’s not a wine you can drink in quantity, also because it’s so intense and mouth-filling.

The bottle I’m having today is among the very best sherries available on the market. From the négociant house of Emilio Lustau comes this Oloroso Pata de Gallina 1/38, matured by Juan García Jarana. I’ll spare you the technicalities (it’s basically a micro-production from a single grower, which is a very unusual thing in the world of sherry, normally a classic blended and branded wine) and will just say it’s a mindblowingly complex wine. I could write page after page of aroma descriptors and wouldn’t be exhaustive. There’s a unique combination of almondy, nutty, marzipanny, wafery, pâtisserie notes with nuanced fruits ranging from orange and lemon to raspberry, heavier spicy notes of mulled wine, bitter chocolate and caramel, a raisiney richness but also lots of lifted, sandalwoody, varnishy, almost vinegarish scents. But it’s all in balance. It’s a wine that keeps changing in the glass: over half an hour it’s really like an aromatic journey over an amazingly complex landscape. I sit in silence and awe as the wine tells its epic story.

The other remarkable thing is that I’m finishing this bottle that was opened on 30th December 2007. That’s no joke. December 2007, not 2008. That’s 596 days! And I must say the wine is still very much alive. I can’t say it’s unchanged – it has surely lost some complexity – but is still offering more than a fair bit of impact, and length is as staggering as usually in a good oloroso. The wine was completely oxidised in oak barrels over something like twenty years (it’s hard to give a precise period of ageing, as the barrels were regularly refreshed with new wine) and it really couldn’t care less about being exposed to oxygen now. Only madeira can approach this durability. It’s making this wine even more unique. Please drink more dry sherry!

© Manel Armengol / Roda S.A.

The latter element was certainly confirmed by our vertical tasting. None of the wines showed even remotely tired, and even the 1992 (hardly a great vintage in Rioja) held tremendously well for four hours from opening, staying deliciously fruity and fresh. Among the older wines 1996 was very bretty and a little blunt but otherwise showed the customary Roda concentration and balance; 1997 was a little lighter than its siblings with notes of red fruits, and while a little simple it too retained power throughout the evening, showing well with food. All were towered by the outstanding 1994, staggeringly young and tonic, with lots of extract and austerity and no hint of maturing. It just lacked a bit of finesse and allure to be perfect but it was a very big bottle indeed.

But there were problems, also. Two bottles of the 1995 were corked (a pity; I’ve enjoyed this vintage in Rioja), and two of the 2000 were oxidised. The 1998 scored very highly upon opening for its ‘Burgundian’ (my colleagues’ term; I disagreed) architecture but the obvious lack of structure made for a less than convincing evolution in the glass; it was massacred by a beef steak. The 1999 didn’t quite convince, so modern and creamy-oaky it still was after seven years in bottle; perhaps just a problem of middle age.

And then the latest vintages continued along very controversial lines. 2002 was predictably lighter but not light enough; a rainy vintage that was a good occasion to tune down the extract was in the end made a replica of 2001. 2003 was simply port-like in its extravagant alcohol and notes of stewed fruit – unsurprisingly so for 2003 but that’s hardly a consolation. The 2001, once described by a Roda representative as ‘the very best since 1964’, was heavy, chocolatey, alcoholic and unremarkable (though to its credit, it evolved well in the glass). Eventually I preferred the very balanced 2004, although there was no escaping the 14.5% alcohol and the creamy milkshake textural feel to the overvatted tannins.

Proceeding from the older vintages through to the latest ones, this was a puzzling tasting. Normally when I look at new Roda releases (usually at least once per year), I really like the wines and don’t mind the style all that much, although 1) I have always preferred the lighter, juicier, less ‘ambitious’ Roda II (now called Roda Reserva), and 2) the Cirsión supercuvée, which is made along the same lines as the Roda I but multiplied by two, I have usually found an excessive and unsympathetic wine. Yet this vertical tasting magnified the stylistic problem of the latest vintages. Instead of the former 13.5% alcohol we now have 14–14.5%, and while Roda has never been a high-acid wine, significantly I used the word ‘fresh’ in my tasting notes for all vintages through 1997 but ‘soft’, ‘creamy’ and ‘blunt’ for all since 2001. This is arguable but in my book Tempranillo really doesn’t take late harvest very well, and I actually prefer it a bit on the green side, especially when it has many years to mature to integrate that greenness.

In the end Roda I is a prestigious bottling that deserves the benefit of a doubt, and you might say the successful recent vintages like 2001 and 2004 are likely to evolve along the same lines as the 1994 or 1996. But noticing this subtle stylistic change, I doubt they will.

© Manel Armengol / Roda S.A.

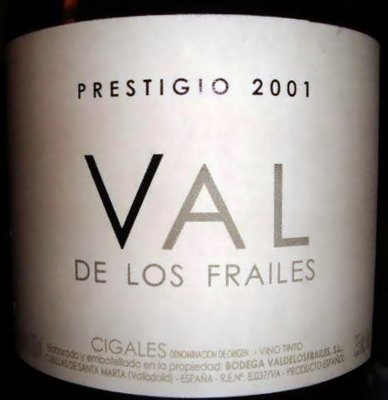

I brought a bottle of Valdelosfrailes Cigales Prestigio 2001. Valdelosfrailes belongs to

Matarromera, a large producer from Ribera del Duero (the group’s other brands are inexpensive Emina and top-drawer Renacimiento). The overall quality is very reliable, although the style is somewhat commercial and safe. I have always liked the offerings from Valdelosfrailes, especially the Vendimia Seleccionada which I find one of the best value for money Tempranillo wines from Castile. I have never before tried the Prestigio, though. In all honesty, it is a little banal. There is good concentration but on the palate, the wine shows why Cigales will never be Ribera del Duero: depth and complexity are moderate, and the 14 months of American oak are showing. I don’t see this wine improving further (in fact, it might have shown better a year or two ago, with fresher fruit). From his cellar, R. generously offered the Almaviva 1998. I drink Chilean wine even more rarely than Spanish, and don’t think I ever tried a 10-year-old prestigious bottling like this. A very good wine but needs drinking now. Upon opening at cellar temperature, it is a little reticent, and shows a certain Bordeauxesque meatiness to the profile. Colour starts to acquire a warm reddish hue, aromas are blended into a harmonious and inviting if not terribly sophisticated or complex whole. Mouthfeel is comfortable, with well integrated oak and no greenness (which I detect in the majority of even the most expensive Chileans). With time in the glass, there is more sweetness and obvious New World character, although the French influence is always detectable. This is really quite good and drinking nicely now, but on the other hand, it doesn’t really have a lot of dimension. When I think current releases cost upwards from 40€ per bottle, Almaviva is quite overpriced.

From his cellar, R. generously offered the Almaviva 1998. I drink Chilean wine even more rarely than Spanish, and don’t think I ever tried a 10-year-old prestigious bottling like this. A very good wine but needs drinking now. Upon opening at cellar temperature, it is a little reticent, and shows a certain Bordeauxesque meatiness to the profile. Colour starts to acquire a warm reddish hue, aromas are blended into a harmonious and inviting if not terribly sophisticated or complex whole. Mouthfeel is comfortable, with well integrated oak and no greenness (which I detect in the majority of even the most expensive Chileans). With time in the glass, there is more sweetness and obvious New World character, although the French influence is always detectable. This is really quite good and drinking nicely now, but on the other hand, it doesn’t really have a lot of dimension. When I think current releases cost upwards from 40€ per bottle, Almaviva is quite overpriced.